The Berkeley physicists were intrigued by the possibility of a fusion bomb, but much less sure of its feasibility. As a result, it was not accorded a high priority during the war years. As of 1945, work on the H bomb (as the fusion bomb came to be called [1] The H bomb, or hydrogen bomb, is also called a thermonuclear weapon, because its operation requires high temperature— extremely high temperature.

) had not led to a brighter prospect for its success. If anything, the work in the intervening years made the prospect dimmer. Nevertheless, work continued, for the H bomb, if it could be made to work, would be far more powerful than an A bomb, and might be less costly to make. For those concerned with “more bang for the buck,” it was an attractive option. For some others, it was almost too horrendous to imagine. Yet nearly all the physicists and policy makers agreed that work to establish its feasibility (or not) should continue.

As of 1950, when I joined the effort, there had been no breakthrough, and the likelihood of success in building an H bomb was at best clouded. Then, in the spring of 1951, came an idea that was a breakthrough. That is where my story begins.

On March 9, 1951, Edward Teller and Stan Ulam issued a report, LAMS 1225, [2] As an LAMS report (MS for manuscript), it was lesser ranked (or more informal) than an LA report.

at the Los Alamos Scientific Lab [3] Now the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

where they both worked at the time. It bore the ponderous, hardly illuminating title “On Heterocatalytic Detonation I. Hydrodynamic Lenses and Radiation Mirrors,” and it changed everything. Since it dealt with thermonuclear weapons (H bombs), it was, of course, classified secret. For some reason, it remains secret to this day. The highly redacted version of it that can be found on the Web {1} 1 http://www.nuclearnonproliferation.org/LAMS1225.pdf

is mostly white space. Nevertheless, most of what was in it is well known.

Their big idea, which we refer to now as radiation implosion, was that the electromagnetic radiation (largely X rays) emitted by a fission bomb, if appropriately channeled, could compress and heat a container of thermonuclear fuel sufficiently that that fuel would be ignited and the nuclear flame would propagate, not fizzle. The expected result: megatons of energy, not kilotons. [4] A “ton” of energy is the nominal energy released when one ton of high explosive blows up (for the record, it is 4.2 billion joules). The energy released in nuclear explosions is measured in thousands or millions of tons (kilotons or megatons). The Hiroshima bomb, the first nuclear weapon used in war, had an estimated “yield” of 13 to 15 kilotons. The second weapon, dropped on Nagasaki, yielded about 21 to 23 kilotons. In subsequent tests, the yields have been measured with greater precision. To put all of this in human terms, a ton of explosive energy is about the same as a million food calories, enough to keep a human going for about 500 days. A kiloton would “feed” a thousand people for 500 days. A megaton, spread over that same period of time, would nourish a million people. But that same megaton, released in a fraction of a second in the right place could slaughter a million people.

History validated the Teller-Ulam idea. (In the end, it was even more effective than they first imagined.) On exactly who contributed what to that big idea, history is a little fuzzier. More on that below. (Here and in what follows, I use “Teller-Ulam” not to anoint Teller as the senior author but only to keep the authors in alphabetical order, as they are on the report’s cover.)

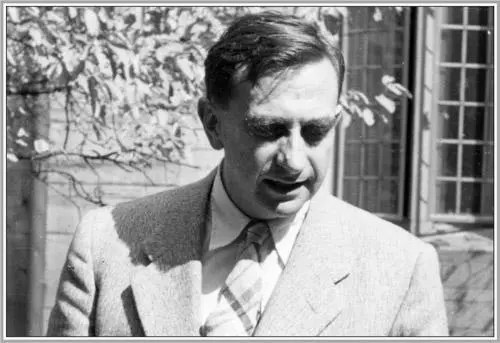

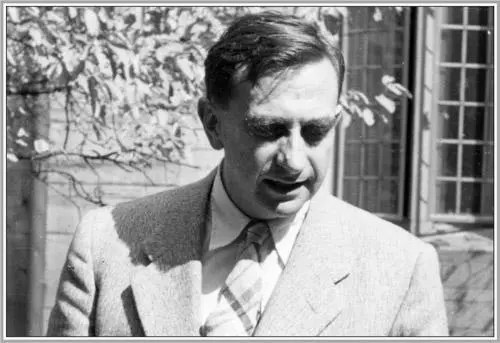

Stan Ulam, 1951.

Courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection.

Stanislaw Ulam (always known as Stan) and Edward Teller (always Edward, never Ed) had some things in common. They were both émigrés from Eastern Europe—Stan from Poland, Edward from Hungary. They were both brilliant. They both had great curiosity about the physical world. And they were both a bit lazy. But oil and water also have some things in common. Stan and Edward differed more than they were alike. Stan, a mathematician with a gift for the practical as well as the abstract, was—to use current slang—laid-back. He had a droll sense of humor and a world-weary demeanor. He longed for the Polish coffee houses of his youth and the conversations and exchanges of ideas that took place in them. Edward was driven—driven by fervent anticommunism, by a desire to excel and be recognized—driven, it often seemed, by internal demons. Edward was too intense to show much sense of humor. Stan had an abundance of humor. Stan and Edward did not care very much for each other (which may help to explain why a “Heterocatalytic Detonation II” report never appeared).

Edward Teller, 1951.

Courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Gift of Carlo Wick.

I was a twenty-four-year old junior physicist on the H-bomb design team at Los Alamos when the Teller-Ulam report was issued. I saw Stan and Edward every day. I liked them both, and continued to like them, and to interact with them now and then, for the rest of their lives. Stan and I later wrote a paper together, on using planets to help accelerate spacecraft (the so-called “slingshot effect”). Edward and I later worked together as consultants to aerospace companies in California.

Not everyone at the lab had equal affection for these two men. Carson Mark, the Canadian mathematician turned research administrator who headed the Theoretical Division during the H-bomb period, could scarcely abide Edward. He liked Stan, even if Stan didn’t care much for bureaucratic nice-ties and even if Stan sometimes wanted to chat when Carson wanted to work. John Wheeler, my mentor, although a straight-arrow quintessential American (he was born in Florida and raised in California, Ohio, and Maryland), was Edward’s soul mate. They were completely in tune in their anti-Communism and their fear of Soviet aggression. Balancing their pessimism about world affairs, they shared an optimism that nature would, in the end, abandon all resistance and yield her secrets if they just pressed hard enough. They had done some joint research together back in the 1930s (on the rotational properties of atomic nuclei) and their wives, Mici (MITT-cee) Teller and Janette Wheeler, were friends. It was Edward’s persuasion, in large part, that led Wheeler to interrupt a sabbatical in France and take a leave of absence from his academic duties at Princeton to spend the 1950-51 year at Los Alamos. Wheeler didn’t exactly dislike Stan, he just didn’t resonate with him. (There were, in fact, very few people whom Wheeler didn’t like, and he tried hard to mask whatever negative feelings he had toward those few.) For Wheeler’s taste, Stan was just a bit too laid-back, a bit too nonchalant.

Looking back, the odd thing to me now is that the Teller-Ulam idea, at the time it was advanced, didn’t shake the Earth under our feet. There were vibrations, but no earthquake. There was a new sense of cheer, but no parties or toasts or flag waving. We didn’t take the trouble to analyze, as so many have since, who exactly had what part of the idea and who deserves the greater credit. Years later, Edward said to me (I paraphrase), “Stan had a dozen ideas a day. They were almost all crazy. He himself had no idea which ones were valuable. It took me to pick out of the jumble the one good idea and exploit it.” Also years later, Stan said to me (again, I paraphrase), “Edward just couldn’t bring himself to admit, after his years of effort, that the idea on how to make the H bomb work was mine. He just had to take it and call it his own.”

Читать дальше