The Bomb Vessel

Richard Woodman

For

OSYTH LEESTON

with many thanks

'Whenever I see a man who knows how to govern, my heart goes out to him. I write to you of my feelings about England, the country that… is ruled by greed and selfishness. I wish to ally myself with you in order to end that Government's injustices.'

TSAR PAUL TO BONAPARTE, 1800

Chapter One

A Fish Out of Water

September 1800

Nathaniel Drinkwater did not see the carriage. He was standing disconsolate and preoccupied outside the bow windows of the dress-shop as the coach entered Petersfield from the direction of Portsmouth. The coachman was whipping up his horses as he approached the Red Lion.

Drinkwater was suddenly aware of the jingle and creak of harness, the stink of horse-sweat, then a spinning of wheels, a glimpse of armorial bearings and shower of filth as the hurrying carriage lurched through a puddle at his feet. For a second he stared outraged at his plum coloured coat and ruined breeches before giving vent to his feelings.

'Hey! Goddamn you, you whoreson knave! Can you not drive on the crown of the road?' The coachman looked back, his ruddy face cracking into a grin, though the bellow had surprised him, particularly in Petersfield High Street.

Drinkwater did not see the face that peered from the rear window of the coach.

'God's bones,' he muttered, feeling the damp upon his thighs. He shot an uneasy glance through the shop window. He had a vague feeling that the incident was retribution for abandoning his wife and Louise Quilhampton, and seeking the invigorating freshness of the street where the shower had passed, leaving the cobbles gleaming in the sudden sunshine. Water still ran in the gutters and tinkled down drainpipes. And dripped from the points of his new tail-coat, God damn it!

He brushed the stained breeches ineffectually, fervently wishing he could exchange the stiff high collar for the soft lapels of a sea-officer's undress uniform. He regarded his muddied hands with distaste.

'Nathaniel!' He looked up. Forty yards away the carriage had pulled up. The passenger had waved the coach on and was walking back towards him. Drinkwater frowned uncertainly. The man was older than himself, wore bottle-green velvet over silk breeches with a cream cravat at his throat and his elegance redoubled Drinkwater's annoyance at the spoiling of his own finery. He was about to open his mouth intemperately for the second time that morning when he recognised the engaging smile and penetrating hazel eyes of Lord Dungarth, former first lieutenant of the frigate Cyclops and a man currently engaged in certain government operations of a clandestine nature. The earl approached, his hand extended.

'My dear fellow, I am most fearfully sorry…' he indicated Drinkwater's state.

Drinkwater flushed, then clasped the outstretched hand. 'It's of no account, my lord.'

Dungarth laughed. 'Ha! You lie most damnably. Come with me to the Red Lion and allow me to make amends over a glass while my horses are changed.'

Drinkwater cast a final look at the women in the shop. They seemed not to have noticed the events outside, or were ignoring his brutish outburst. He fell gratefully into step beside the earl.

'You are bound for London, my lord?'

Dungarth nodded. 'Aye, the Admiralty to wait upon Spencer. But what of you? I learned of the death of old Griffiths. Your report found its way onto my desk along with papers from Wrinch at Mocha. I was delighted to hear Antigone had been purchased into the Service, though more than sorry you lost Santhonax. You got your swab?'

Drinkwater shook his head. 'The epaulette went to our old friend Morris, my lord. He turned up like a bad penny in the Red Sea…' he paused, then added resignedly, 'I left Commander Morris in a hospital bed at the Cape, but it seems his letters poisoned their Lordships against further application for a ship by your humble servant.'

'Ahhh. Letters to his sister, no doubt, a venomous bitch who still wields influence through the ghost of Jemmy Twitcher.' They walked on in silence, turning into the yard of the Red Lion where the landlord, apprised of his lordship's imminent arrival by the emblazoned coach, ushered them into a private room.

'A jug of kill-devil, I think landlord, and look lively if you please. Well, Nathaniel, you are a shade darker from the Arabian sun, but otherwise unchanged. You will be interested to know that Santhonax has arrived back in Paris. A report reached me that he had been appointed lieutenant-colonel in a regiment of marines. Bonaparte is busy papering over the cracks of his oriental fiasco.'

Drinkwater gave a bitter laugh. 'He is fortunate to find employment…' He stopped and looked sharply at the earl, wondering if he might not have been unintentionally importunate. Colouring he hurried on: 'Truth to tell, my lord, I'm confounded irked to be without a ship. Living here astride the Portsmouth Road I see the johnnies daily posting down to their frigates. Damn it all, my lord,' he blundered on, too far advanced for retreat, 'it is against my nature to solicit interest, but surely there must be a cutter somewhere…'

Dungarth smiled. 'You wouldn't sail on a frigate or a line of battleship?'

Drinkwater grinned with relief. 'I'd sail in a bath-tub if it mounted a carronade, but I fear I lack the youth for a frigate or the polish for a battleship. An unrated vessel would at least give me an opportunity.'

Dungarth looked shrewdly at Drinkwater. It was a pity such a promising officer had not yet received a commander's commission. He recognised Drinkwater's desire for an unrated ship as a symptom of his dilemma. He wanted his own vessel, a lieutenant's command. It offered him his only real chance to distinguish himself. But passed-over lieutenants grew old in charge of transports, cutters and gun-brigs, involved in the tedious routines of convoy escort or murderous little skirmishes unknown to the public. Drinkwater seemed to have all the makings of such a man. There was a touch of grey at the temples of the mop of brown hair that was scraped back from the high forehead into a queue. His left eyelid bore powder burns like random ink-spots and the dead tissue of an old scar ran down his left cheek. It was the face of a man accustomed to hard duty and disappointment. Dungarth, occupied with the business of prosecuting an increasingly unpopular war, recognised its talents were wasted in Petersfield.

The rum arrived. 'You are a fish out of water, Nathaniel. What would you say to a gun-brig?' He watched for reaction in the grey eyes of the younger man. They kindled immediately, banishing the rigidity of the face and reminding Dungarth of the eager midshipman Drinkwater had once been.

'I'd say that I would be eternally in your debt, my lord.'

Dungarth swallowed his kill-devil and waved Drinkwater's gratitude aside.

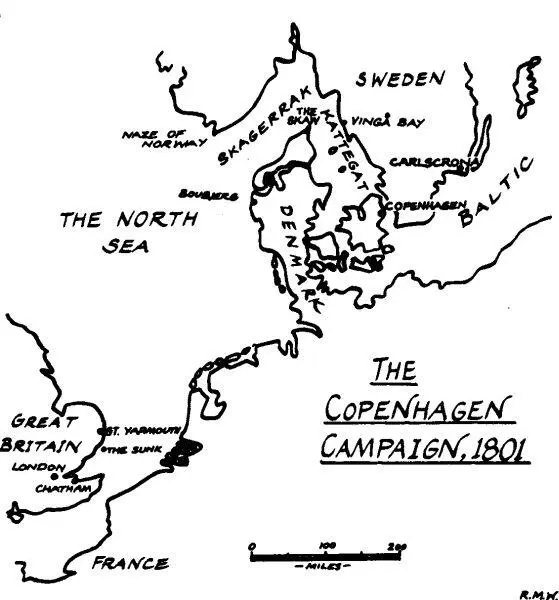

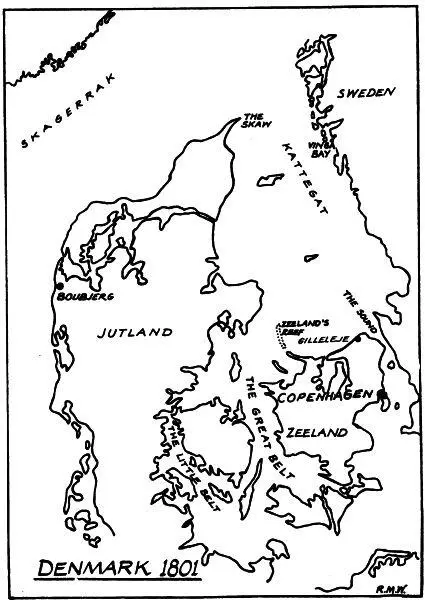

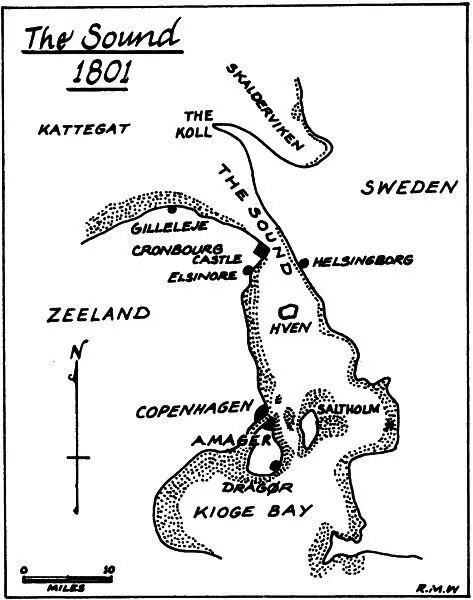

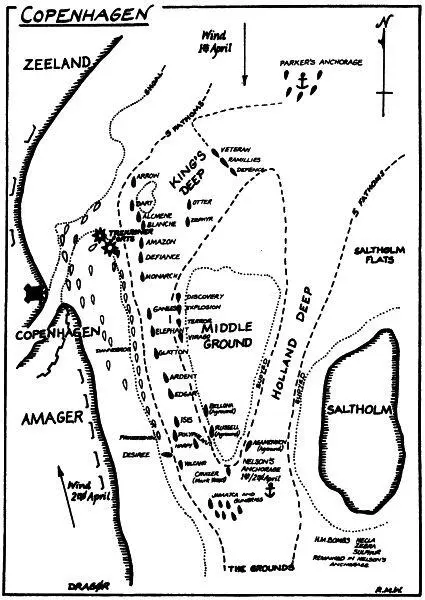

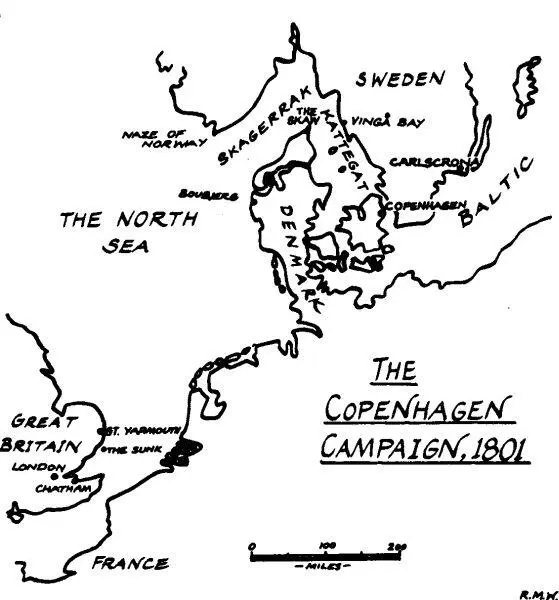

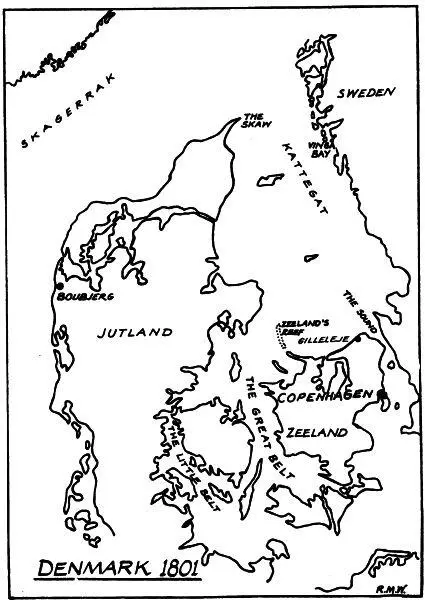

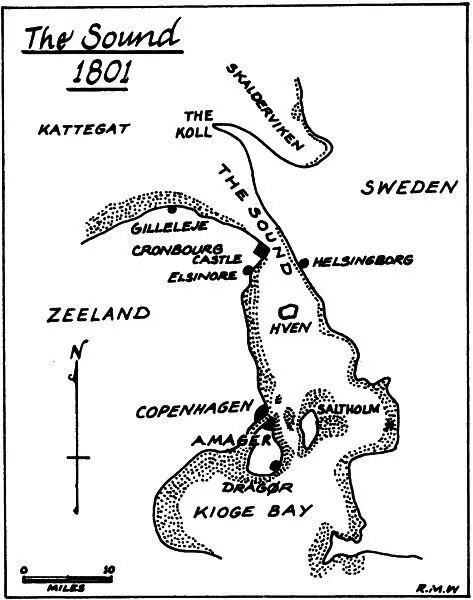

'I make no promises, but you'll have heard of the Freya affair, eh? The Danes have had their ruffled feathers smoothed, but the Tsar has taken offence at the force of Lord Whitworth's embassy to Copenhagen to sort the matter out. He resented the entry of British men of war into the Baltic. I tell you this in confidence Nathaniel, recalling you to your assurances when you served aboard Kestrel …'

Читать дальше