ibidem-Press, Stuttgart

Contents

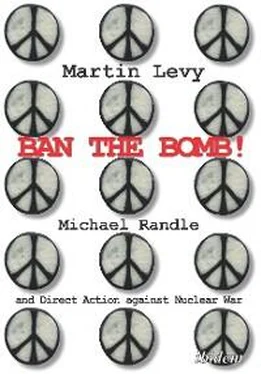

Foreword Foreword This book is a delight on many levels. First, Martin Levy gives us a history of a remarkable man in a thoroughly absorbing way. Through many discussions with Michael, as well as some with Anne, he takes us through a life well lived, with many illustrations that help to give us an idea of where Michael came from and what helped make him. Through a series of interviews stretching over many months, we build a picture not just of Michael but of the history of nonviolent action in Britain over seven decades. It is a thoroughly unusual approach to biography, but it works a treat. Then there is Michael himself, peace-campaigner, activist, scholar and much more, ready to go to prison for his beliefs yet gentle and patient in his determination to do the right thing. Most of his life’s work has been in Britain, but the span of his contacts is global and through the interviews we come in contact with many of the leading campaigners and thinkers on nonviolence over all of those decades. That alone gives us a unique perspective on an informal yet resolute belief system that is always there and comes to the fore in unexpected ways, whether in peace campaigning, civil rights movements, the collapse of the Soviet system, or in other contexts. There are also interludes when the unexpected suddenly intrudes, not least the astonishing and successful attempt to spring the spy George Blake from Wormwood Scrubs Prison and to keep him hidden at various locations in London. The hair-raising story of how Blake’s cover was almost blown by Michael’s encounter with a friend’s wife outside a tube station in London is remarkable enough, but to add to this we have the trial of Michael and Pat Pottle, a co-conspirator, at the Old Bailey many years later. Their acquittal was unexpected and so the powers-that-be inevitably termed it the action of a ‘perverse jury’, but it would still make a marvellous film. There is also Michael the scholar, not just his core role in the Alternative Defence Commission’s pioneering work on non-nuclear defence back in the 1980s, but his own work on nonviolence and civilian resistance and his wider contributions to the Bradford School of Peace Studies. I have been fortunate to have known Michael for forty years and have been lucky to work with him on several occasions. In his own quiet way, and with no fuss, he persists in his optimism against the odds and serves as a remarkable inspiration to many. This book is a fitting tribute to a remarkable person. Paul Rogers, June 2020.

Introduction

1. Family and Schooling

2. The Birth of a Satyagrahi

3. The Direct Action Committee and the first Aldermaston March

4. Peace News and Ghana

5. The Committee of 100

6. Marriage, The ‘Official Secrets’ Trial and Prison

7. Greece, Vietnam, and George Blake

8. The Greek Embassy ‘Invasion’ and Czechoslovakia

9. Peace Studies and the Alternative Defence Commission

10. The Blake Trial

11. Bradford University and Final Thoughts

Chronology

Acknowledgements

Further Reading

This book is a delight on many levels. First, Martin Levy gives us a history of a remarkable man in a thoroughly absorbing way. Through many discussions with Michael, as well as some with Anne, he takes us through a life well lived, with many illustrations that help to give us an idea of where Michael came from and what helped make him. Through a series of interviews stretching over many months, we build a picture not just of Michael but of the history of nonviolent action in Britain over seven decades. It is a thoroughly unusual approach to biography, but it works a treat.

Then there is Michael himself, peace-campaigner, activist, scholar and much more, ready to go to prison for his beliefs yet gentle and patient in his determination to do the right thing. Most of his life’s work has been in Britain, but the span of his contacts is global and through the interviews we come in contact with many of the leading campaigners and thinkers on nonviolence over all of those decades. That alone gives us a unique perspective on an informal yet resolute belief system that is always there and comes to the fore in unexpected ways, whether in peace campaigning, civil rights movements, the collapse of the Soviet system, or in other contexts.

There are also interludes when the unexpected suddenly intrudes, not least the astonishing and successful attempt to spring the spy George Blake from Wormwood Scrubs Prison and to keep him hidden at various locations in London. The hair-raising story of how Blake’s cover was almost blown by Michael’s encounter with a friend’s wife outside a tube station in London is remarkable enough, but to add to this we have the trial of Michael and Pat Pottle, a co-conspirator, at the Old Bailey many years later. Their acquittal was unexpected and so the powers-that-be inevitably termed it the action of a ‘perverse jury’, but it would still make a marvellous film.

There is also Michael the scholar, not just his core role in the Alternative Defence Commission’s pioneering work on non-nuclear defence back in the 1980s, but his own work on nonviolence and civilian resistance and his wider contributions to the Bradford School of Peace Studies.

I have been fortunate to have known Michael for forty years and have been lucky to work with him on several occasions. In his own quiet way, and with no fuss, he persists in his optimism against the odds and serves as a remarkable inspiration to many. This book is a fitting tribute to a remarkable person.

Paul Rogers, June 2020.

The Judge asked if there was any justification for breaking the law?

‘An individual has to make a decision where millions of lives are concerned.’

‘Does that mean you and other members of the Committee of 100?’

‘Every individual must decide ... . Every individual has to decide between the law and his own morality.’

Mr Justice Havers ‘in dialogue’ with Michael Randle. 1

Anyone who has ever read a book about civil rights or taken part in an illegal demonstration will recognise the above distinction between law and personal morality, state power and the promptings of the individual conscience. It was some such distinction that inspired the Biblical Daniel to defy a decree of the Babylonian King Darius, and which led to the execution of Socrates for impiety and demoralising the young people of Athens in 399 BCE.

The issue that confronted the jury in Court No.1 of the Old Bailey during February 1962 was the morality of bombing civilians with nuclear weapons. The state in the person of its chief witness, Air Commodore Graham Magill, said that should circumstances so demand it, it was moral. Michael Randle and his co-defendants, to their credit, took the contrary view.

The proximate cause that brought Michael to the Old Bailey trial was a blockade and mass trespass of the NATO air base at RAF Wethersfield, in Essex, a little over three months earlier. On trial were Michael and his five co-defendants: Terry Chandler, Ian Dixon, Pat Pottle, Trevor Hatton and Helen Allegranza, all senior officers in the Committee of 100, an organisation set up to campaign by non-violent means for nuclear disarmament.

They were charged on two counts under section one of the Official Secrets Act of 1911: first, conspiring together to commit a breach of the Act by entering the air base for a ‘purpose prejudicial to the safety or interests of the State’ and second, conspiring to ‘incite others to do likewise.’ 2

As for the distant causes which led to the prosecution, I’ll say a bit more about those later on.

Here it is enough to state that Michael and his co-defendants were anything but political or legal innocents. They knew their rights. No wonder they got up the nose of the haughty and contemptuous chief prosecuting council, the Attorney-General, Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller.

Читать дальше