As soon as the sleigh arrived at camp, the doctor came to see us. They gave us hot tea and a slice of bread, but I was unable to eat or drink, and the doctor, who was a woman, paid more attention to me. She realized immediately that I was in serious condition and gave me an injection. My surroundings were obliterated as I lay in a pool of darkness and rest. In my drugged state of mind, I thought I saw my mother and sister and talked with them. My heart and soul were always at home.

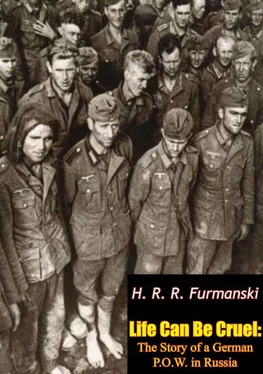

After a few days I found myself back again in a so-called isolation room. It took me almost three weeks to get on my feet, but I had to stay in the sickroom four more weeks. Upon my release from the sickroom, I realized my new place of confinement was not a bit better than the places where I had previously been held captive. Camp Yelabuga had been the residence of some priests in the era of the czars. Here too the beautiful buildings were in a state of decay. The church was used as a storage house for food and empty boxes, the main building housing more of the prisoners. Plank beds had been built in the rooms, each person having a space of about thirty-five inches. Fifteen hundred men were in this camp, sixty being confined in one room.

In January, 1944, the commandant of this camp issued a bulletin to the effect that the camp had to manage itself. This meant that we had to carry our own wood for the bakeshop, kitchen, laundry, etc., keep the water pumps in working condition, man the electric station and provide all necessities for our daily life. Under the supervision of a captured German officer, who was called the camp-leader, different labor groups were set up, some working in the kitchen, others in the bakeshop, in the laundry, on the water pumps, electric station, and ambulance. All of these groups found the work difficult, but the hardest work was carrying the wood for the entire camp. Early in the morning this group marched out, coming back at night with the wagon loaded with wood. They had to pull the wagon themselves, since no horses were provided, and in wintertime sleighs were used in place of the wagon. For this work in the wood brigade the men got four ounces more of bread and a thicker soup, extra food coming from the rations of the other men, rather than from an increase in food delivered to the camp. The result was that the soup for the rest of us was much more watery that it had been. All of us tried very hard to go only once with the wood brigade, in order that the thicker soup might be evenly apportioned among us all. The strain to our bodies meant nothing to us: it was important only that we fill up once in a while.

In the meantime America had made an agreement with Russia to help the Russian population and the prisoners of war. When the provisions of this pact began to be carried out, we felt a little more secure; more drugs were available and the mortality rate dropped, due in part to the fact that the prisoners were becoming better adjusted to this kind of life. The daily ration was still the same, but at least we could count on getting it, which had not always been the case heretofore. Each prisoner was given a daily minimum of six hundred grams of dark rye bread, which contained 60 per cent water, ten grams of flour or peas or potatoes, ten grams of oil or fish, and ten grams of sugar. In comparison, one ounce is equivalent to twenty-eight grams. I had been in Yelabuga almost three years, but it was still only 1944, and every day and month seemed an eternity. Most nerve-racking of all, we had to listen to the news over the radio; the polit commissar turned on the radio so that we could hear how the Russian Army was repelling the German Army and that Germany would soon be the battlefield. We still had hopes that the war would be over soon and that we could go home. In December, 1944, German towns were mentioned for the first time in the news, and we sat listening while our hopes of ever seeing our relatives again died within us. We were still thousands of miles away from home in 1945, and the Russian Army was in Germany, with thousands of people fleeing from East Prussia while we remained captive in Russia, starving and waiting to return to our homes. Our thoughts on New Year’s Eve, 1944, were of home, and we were praying and hoping for a happy 1945.

In February, 1945, the name of my hometown was mentioned in the news; the town, according to the newscast, was virtually razed after a fierce battle. I sat on my bed and cried, feeling an emptiness inside me and knowing that I would never see my parents again. But my faith was stronger than my emotions, and I persisted in the hope that there would someday be a reunion of all of us. After all these years in prison we found ourselves unable to believe one word the Russians were saying. Our only hope—that America and the free world would ask for release of all prisoners of war—gave us the courage to remain alive. The end of the war, in May, 1945, was a relief for all people on earth. The Russians devoted eight days to celebrating their victory over Nazi Germany. We prisoners thanked the Lord that we were alive, skeletons though we were, hoping still for the chance to return someday and build a new life. Would this be soon, we wondered—or how much longer would we have to stay? Could we carry on much longer under these terrible circumstances?

Several months after the end of the war the Russians brought trainload after trainload of furniture, food, clothing and equipment from Germany: they called this action “reparations.” We saw Russian women dressed in the uniforms of Nazi officers, the stars and medals still on, obviously enjoying what they considered an attractive style. We found the spectacle ludicrous. As we marched our daily route to work, we found that the train station was loaded with all the furniture from Germany, now the property of the State, which made no effort to divide it among the people, leaving it at the mercy of the elements.

The Russian officials declared that we were no longer prisoners of war, giving us instead the title of “reparation workmen.” There did not seem to be a great deal of difference. We lost all hope for our return to Germany. Nobody in the world could enforce our return. Most of the prisoners had died, no records kept of their passing, and now we were reparation workmen. The free world could only conjecture as to how many men had been captured and how many remained alive.

At Christmas, 1945, each one of us was permitted to send a postcard home. It was a propaganda move only, designed to show that Russia made no secret of its captured soldiers. We tried to contact our relatives, but nobody knew where they were living now. I wrote every month to my parents, but never received an answer, nor was my card returned. Few among us had made contact with our families, and most had abandoned hope of a reunion. Somehow I could not relinquish the hope. Perhaps I will find them when I get back, I comforted myself—but when will it be? One year had passed since the end of the war, and our lives had not changed for the better.

In August, 1946, there was great excitement in camp. Russia had decided to send home the first prisoners. We wondered who would be among them—the sick, the dystrophic, the older men? It was a question for which we found no answer. Nobody had any idea as to how the selection was to be made, but every one of us had hopes of being chosen. The list, when it was made public, sealed our disappointment, for only fifty men were being sent home, and those fifty were so ill as to be nearly dead. However, the mere fact that any were being sent was reassuring; surely Russia had to release more of us. Then the free world and the government of Germany would learn about the numerous prisoners still alive in Russia and would claim their return. Unbreakable faith in the humanity of the free world gave us the strength to carry on and the will power to live.

Читать дальше