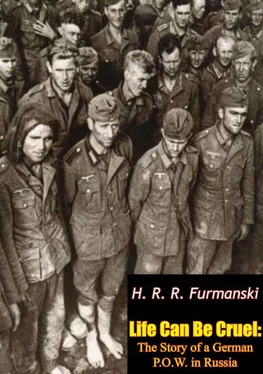

H. Furmanski - Life Can Be Cruel - The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «H. Furmanski - Life Can Be Cruel - The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Pickle Partners Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life Can Be Cruel: The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pickle Partners Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life Can Be Cruel: The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life Can Be Cruel: The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

An astonishing first-hand account.

Life Can Be Cruel: The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life Can Be Cruel: The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Several more days passed before we could see where we were landing: Karpinsk, south of Sverdlovsk in the Ural Mountains. This would be our place to live or to die. The camp itself was bigger than any we had ever seen before. We wondered how many prisoners were here, and whether we would have a chance to be released soon. The more prisoners who were waiting for their return, the smaller our chances would be. To our surprise we found about eighteen hundred men at camp, and our coming brought the total to about two thousand.

As soon as we entered Camp Karpinsk we had to pass all the usual examination and registration. It was a full day before we were divided and placed to our brigades. I found myself in a brigade selected to work in the quarry. It was our job to move the railroad tracks. Every morning when we came to work, a Russian foreman was there handing out shovels, pickaxes, jimmies and jacks; then he gave his instructions to the leader of our brigade. He blew a whistle, at which signal we took up our tools and started our march to the place where we would work, two miles or more from the tool-room. We began work immediately upon arrival, leveling the ground for the new tracks, removing the old tracks from their ties, carrying the tracks on our shoulders as far as one hundred feet, while others dug out the ties preparatory to moving them to the new location. The ties were of oak, weighing up to two hundred pounds, and each tie was carried by two men. Another group had to place the ties, lay and nail down the tracks, level the tracks, and tighten the ties. It was very hard work, especially in winter, we never came close to fulfilling our quota.

We had to work in temperature of thirty-five degrees below zero, and in a section of country which has almost five months of winter. The clothing was entirely inadequate. Many times, when our clothes were wet, we had to dry them inside the barracks. Boots and gloves were of different sizes, and we were forced to exchange them among ourselves in order to achieve a proper fit. Somehow we got through 1948, though we did not count days, months, or years any more. Every morning was a new day, and as long as we were alive we hoped for something unexpected, for some help from the free world. Perhaps America and the Western powers would claim our release, we thought. We knew that the Russians did not care about the opinions of the free world but it was our only hope.

The Russians kept every move a secret, so that no one knew what was going on. They spread some rumors to keep us going, hoping, working. In the spring of 1949 another group was selected to be repatriated. This time only those who would go to East Germany and work there were chosen. Since I had been born in East Prussia, I was on the list to go home. As soon as I entered the ambulance for physical examination, the officer of the state police whispered to the doctor that he believed I was one of Hitler’s SS men, judging by my height and looks. I did not pass the examination, and was forced to return to work. I was bitterly disappointed, having been so near to release, but after a few days I was myself again, hoping for better luck next time. The very same thing happened three times more, and when I was again summoned for the release examination, in October, 1949, I had little hope that I would be chosen. This time, however, my luck seemed to hold; another police officer was on duty, and gave his O.K. for my release. The date for our repatriation was set for November 3, 1949. Excitement was great, for this transport was the fifth to be released, and the departure of this group would leave only five hundred men at Karpinsk. We received new uniforms while waiting for the deadline. The train had been delayed by the deep snow, and, as day after day passed with no word of it, we began to believe that our repatriation was another false alarm. Three more days dragged by in fear, hope, and sorrow, each day seeming to be an eternity. Finally, on November 6, the train arrived, and we breathed freely again. Praise the Lord, we thought, we are finally going home.

As soon as the news was out, we dressed at once and went to the fence. Once more we had to stay in line and wait until our names were called to leave the camp. Outside the fence we had to form groups and wait until the last one had left the camp. One of the Russian officers gave the order, and we marched in silence to the train station, our minds occupied with the future. Each man’s face mirrored his emotion: some were praying, some smiling happily, some fearful as they wondered what they would find at home.

Home. I could not go home, because my hometown was in Russian territory. Where shall I go to look for my relatives? I wondered. But my happiness at leaving this hell on earth was sufficient for the time being, and I knew I would find the strength to look around when I got there.

After an hour’s march we came to the train station; surprisingly, our train was there and waiting. We were counted again, the officer in charge calling the name of each one who was permitted to enter the wagon. This procedure took almost the entire day. Late at night the train pulled out, and we knew we were going home at last. Joy and happiness filled our hearts for the first time in seven years; forgotten were the hardships, fear, and hunger. Thankful for survival, everyone prayed silently and fell asleep smiling happily.

When we awoke next morning, we found that the train was still rolling. This was a surprise, for usually when we rode a train they stopped at night. Our first stop was at noon, at which time they gave us our meal. The soup tasted delicious to us in this cold weather—for we were going home. Besides the soup we were given some bread. As soon as we had finished eating, the engineer blew the whistle and the train began to roll again. We spent twelve days on the train before reaching the Russian-Polish border, where the doors were locked and the guards took turns watching the train and the prisoners. We did not know the reason; some law, we supposed. Next morning we stopped at Brest-Litovsk and had to leave our train, for the Polish government took over our transport through Poland. At Brest-Litovsk, which is the transit station, the tracks are of a different width; therefore, the Russian trains cannot pass through Polish country. After we had left the train we saw that we were in some kind of camp again. In this camp one of our number called for a meeting, at which he read a resolution drawn up by the Anti-Fa. It was a “thank-you” note to Russia for the opportunity to work for Russia and for having been liberated from the Nazi regime; for being still alive and able to work in the future for the interests of the Communist party. Everyone was asked to sign this resolution. I could not and would not sign, discovering later that only a few had signed this statement. After this meeting the Polish government took charge of the whole affair, reading each prisoner’s name, which was then repeated by the prisoner, along with his surname and date of birth, before he could enter the train on the opposite track. After several hours, when the examination was finished, about twenty-five men still remained outside. We did not know what had happened to them, but later we heard that they were wanted for some reason by the Polish government. Our nerves were on edge, tension and fear mixed with our hope. How long, we wondered, would it be till we were free? Hysterical laughter, jokes, and some talk about food could be heard among the crowd. In the eyes of most could be seen fear for the future. Many of us sat silently in a corner, praying for strength. The strain on men who had been so long in prison was almost unbearable.

The train headed west, destination Frankfurt on the Oder, through the formerly German territory of East Prussia and the Corridor, through towns which had once been German territory, now occupied by Poland. What we saw in this part of the country was shocking: towns and villages abandoned, no signs of life at all, weed-grown streets, houses destroyed by war or exposed to the mercy of the elements and the ravages of decay. Some towns, heavily populated before the war, were now occupied by the Polish, with only a few Germans among them. A few of the remaining Germans came to the train station to beg for bread. We did not have much food for ourselves, but we gave them all we had left. They told us their war experiences and begged us to take them with us. We could not do a thing to help them. In my mind I visualized my parents in the same situation; I could think of nothing more terrible in life than to find my parents begging for bread. My fear grew within me, as I wondered where I should look for my parents and sister. Perhaps they had had the chance to flee East Prussia and save their lives. It was the only hope I had. The ride through this familiar part of my country was as endless as the worries and fear that beset my heart.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life Can Be Cruel: The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life Can Be Cruel: The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life Can Be Cruel: The Story of a German P.O.W. in Russia» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.