On the surface a lighter is a tiny, insignificant source of light, but in total darkness it seemed like a blowtorch illuminating a hundred feet of space. Most miners I knew used one to find their way out of a mine when their main lamp went out. A small butane lighter was very light, durable, and reliable, and, unlike a small flashlight, always worked.

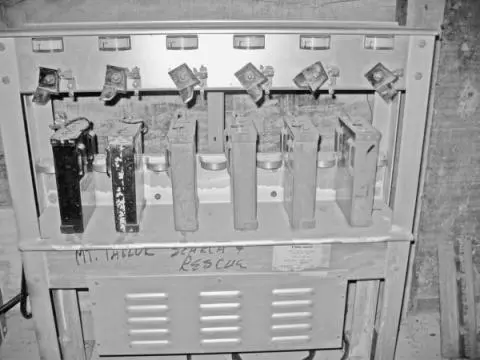

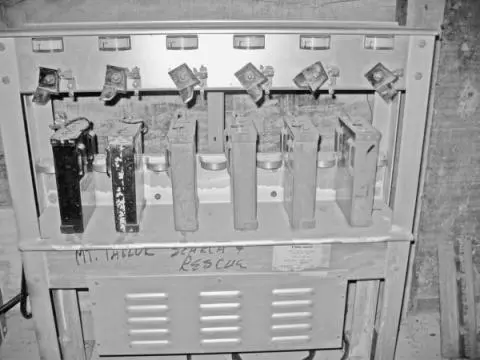

Rack for charging batteries. The gauges visible at the top of the rack above each battery were supposed to indicate the level of charge. These gauges were all too frequently wrong, resulting in a miner with a dead battery being left in the dark, as happened to me more than once (photograph by R.D. Saunders from an exhibit courtesy New Mexico Mining Museum).

Before each shift I would go to the battery rack, where several dozen battery packs were charging. While there were gauges showing the strength of the charge, it was not that unusual to pick up an undercharged unit every now and then despite the gauge showing a full charge.

The battery packs hooked to a miner’s belt, and the headlamp attached to the miner’s helmet. After hooking it all up, I would usually test the lamp before heading down for my shift, but every now and then I would overlook it and take an undercharged battery with me. Even then if the light started getting dim, there was usually time to go back up for another, but not every time.

I had been working several months of twelve-hour shifts and was getting run down. I had been through a bad cold and a bout with strep throat and was overall fatigued, so I wasn’t surprised when I picked up an undercharged battery and found myself with a very weak light one morning.

Occasionally, if Stutts hadn’t shown up and was late, I would head back to the stope. I would slip out, so Bill usually didn’t notice, and Stutts ordinarily showed up anyway. If he didn’t appear in a reasonable amount of time, I would go back to the lunchroom to wait it out.

Of course on the day I picked up the undercharged battery, Stutts failed to show up, and just as I was stewing over what had happened to Stutts and contemplating returning to the lunchroom, my battery went dead, leaving me alone in total darkness.

I sat down and reached for my butane lighter that I usually carried in one of the upper pockets of my overalls and found it missing, so there I was, unprepared, in total blackout, with no way to move safely in any direction. This left me with one option: waiting for the shift boss to make it around sometime that morning. So I sat down and waited.

Hours went by, and while I hadn’t panicked, I was certainly ill at ease. I could well be waiting there until the shift change when the boss would check the in-and-out board and realize I had not returned. He would then either look for me himself or a search party would be sent out and I would be found. But if the boss didn’t notice I was a no-show and had not checked the in-and-out board, I might be sitting there until 4:00 p.m. Kermac bosses were fairly observant of the most important safety measures like the in-and-out board, so I was confident in being found eventually, but it was frustrating sitting there in the dark. It was no longer a game.

Finally, after what I estimated to have been about four hours, I started to see some light coming from the manway and heard steps coming up the ladder. Must be the shift boss, I thought. Sure enough, a boss from day shift, Bill Purcell, had noticed me missing and had started searching on his own. Thank you, Bill. It was an interesting few hours and taught me a little bit about what total darkness really is.

In mining, there are all sorts of mechanical sounds, from those muf fled, rumbling explosions that I loved to hear to the sounds of the shifting earth and creaking timber that I didn’t like so much.

Smells were also unique to underground mining. The relatively confined spaces could have contributed to that, but I never again experienced those smells after I left underground mining.

My favorite smell was the one associated with drilling. The combination of compressed air, water, heat, and oil was special. I never heard anyone else mention it or thought to bring it up myself, so maybe it was just me, but I loved it.

Most of the machines at Section 35—muckers, drills of all kinds, and chippers—were run by compressed air, and they all produced different smells. Different kinds of rock had specific smells too. Uranium itself I could smell and differentiate depending on the grade. Mostly we mined uranium that was close to black. That was the good stuff, but the very high-grade ore was sometimes close to yellow, and the two had a different smell. (As an aside, only the very best miners mined high-grade uranium at Section 35, but every now and then a miner like myself would run into some on a small scale.)

I always especially enjoyed walking down the main track drift as the place where so many odors were combined with the fresh air rushing out of the main shaft.

As I mentioned, total darkness was an experience. So was light. In total darkness any light source brightens a very wide area. I was always amazed by what those portable butane lighters could do in that respect. A match could do the same thing.

It became much easier to imagine how civilizations managed to function at night before the invention of the electric light. Gas lamps I’m sure worked very well at night, as would oil lamps and candles—or, for that matter, how miners worked for many years using carbide headlamps and before that candles.

It doesn’t sound like much, but the miner’s lamp that we had attached to our hardhats was a major technical advance in mining. In total darkness, it easily lit up a very large area. Combined, a miner’s and a helper’s lamps easily lit up the immediate area they were working in.

Any light source could be a seen a long way off. That’s why the relatively low-powered trip light on the back of an ore car was so effective. In otherwise total blackness, you could see that thing coming toward you with no problem.

Light was also used as a communications device underground. If you were too far away from someone or if it was too noisy to hear them, the headlamp was used to send signals. For example, moving your headlamp up and down meant to back away or go away, and a circular motion meant come forward.

An individual walking down the main track drift two hundred or more yards away was very easily seen, so we always knew when someone was around or approaching. There was no chance for a shift boss to sneak up on us as we worked in a stope because we could see his head lamp and even the glow of it as he climbed the manway. (As a rule, incidentally, I never liked the shift boss to come around. Nothing personal, but a shift boss visit cost money because it meant stopping whatever I was doing.)

The 812 was developing into a stope with depth but not much width. It couldn’t have been more than twenty yards across, and there were now three stories of eight-foot square-sets. We were working well over five hundred feet from the manway entrance.

One day I was drilling a round when Stutts motioned to me that there was light down by the manway. It wasn’t the usual time for Bill to come around for a visit, but obviously someone was on the way. I stopped drilling and with my headlamp motioned the visitor, who had stopped, to come forward.

Whoever it was stayed put. I thought that was unusual, so I told Stutts, “I’ll go check it out.”

As I started back toward the manway, weaving between the posts of the square-sets, the light vanished. That was odd.

Читать дальше