Then I noticed that my miner’s headlamp, having been submerged, was still working just fine. That’s pretty cool, I thought, great engineering.

I then started congratulating myself on a job well done. The chute lip was no longer stuck, the chute itself was empty, and nobody had gotten hurt. It was all working out. Not exactly.

From down the drift I could see a light rapidly approaching and then the figure of Frankie, emerging from the darkness, running toward us. I was thinking he would be happy to know Anthony and I were OK and that I could show him we had indeed accomplished the opening of the ore chute. We might have messed up and let the water out, but nothing seemed damaged, and we had lived, so Frankie would be pleased. Frankie was not pleased.

Red faced and enraged, Frankie let loose with a string of expletives unlike any I had heard underground up until then. “You stupid cocksucking, motherfucking idiots. You flooded the drift all the way down to the station. It’s a fucking mess, you assholes. Get up to the fucking surface.”

Obviously the chute being again operable was of no consequence to Frankie. Too stunned from the event anyway, I didn’t mention it, electing instead to follow instructions and head back to the station with Anthony.

As we were walking through the drift, I could see what a mess it was. The force of the water had taken a lot of loose rock from the ribs and deposited it on the track. Nothing big, but there was going to be a lot of hand mucking to do to clear the track. “Looks like we’ll have a lot of work to do cleaning this mess up,” I said to Anthony.

“I guess so” was all he said back to me.

None of Frankie’s diatribe upset me much. I was just thrilled to have survived, and, although completely soaked, I otherwise seemed uninjured.

As Frankie had been storming down the drift, I’m sure if he could have fired us he would have, but since we were still alive and the mine was desperate for bodies, we still had jobs. Although we’d survived I always felt certain that had we drowned, Frankie would have fired us posthumously, telling everyone, “You know, I’d have fired those motherfuckers.”

Back at the station, Anthony and I called the hoist-man for a man-trip back to the surface, where word of the incident had already preceded us into the office of Mel Vigil, who was awaiting our arrival.

Over a month had passed since I had last been in Mel’s office. As I stood there in the doorway, soaked from head to toe, dripping water onto the floor, the sight could have been no less amusing than that first day I had appeared before him, dressed in my new clothes with shiny gear in hand. Sure enough, there on his face, I noticed, was the same bemused look.

I never once considered that either I or Anthony might be fired, and in fact, Mel didn’t seem nearly as upset as Frankie had been. All he asked for was an explanation and a few details of the incident.

I told him how, by the use of the powder, we had managed to successfully open the ore chute door. We had been unable to stop the flood once it started, and Anthony and I both had gone underwater. Mel, having undoubtedly seen far bigger knucklehead moves during his career, did not seem particularly upset by any of it and told us to dry off then report to the Dry foreman, who would put us to work. Finally, he told us to be ready to go back down, meaning back to work underground, the next morning.

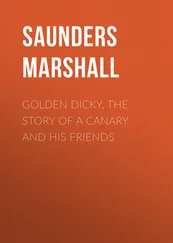

Ore chute door on the main track drift. The top of an ore car is visible directly underneath the door. The pneumatic arm with compressed air hoses attached opened and closed the door and was operated via a small handle to the right that is not visible in this photograph (photograph by R.D. Saunders from an exhibit courtesy New Mexico Mining Museum).

After the incident with the 907 chute, I didn’t expect to get many good assignments from Frankie. On the other hand, I had been filling in latrines and hadn’t gotten a job that might be considered pleasurable up to that point anyway, so whatever he had in mind for me, I was ready for it.

Thankfully, Frankie didn’t hold any grudges, and the following day he greeted Anthony and me both as if nothing had happened. In fact, it was this day that I got my first assignment to work with an actual miner.

As Frankie approached me in the lunchroom the following morning, I was ready to hear more on the subject of what I had done at the 907 chute and how worthless I was. Instead, I was surprised to find that he seemed to be in a better mood. “Listen,” he said, “Schultz is on vacation for a couple of weeks, I put Riordan’s helper on opposite shift, so I’m putting you with Al Riordan. Catch a ride on Bordan’s motor. He’s going back with some stuff for Riordan. Tell him he’s giving you a ride. Don’t fuck up.”

Inwardly ecstatic, I told Frankie I wouldn’t fuck up and headed out of the lunchroom door to the dump station looking for motorman Jim Bordan, who would give me a ride down the main drift to the termination heading where Riordan was working.

Incidentally, Oscar Schultz was one of the toughest men I ever saw at Section 35. He was German and had worked in mines all over the world and really knew his craft. A very friendly guy, he was superior at working track drift mining.

A shortcoming of his was that he broke almost every single safety rule there was. He did wear a hard hat, but that was about it.

I once had to deliver some supplies to him at the heading where he was working. As I approached the area, I could tell there was no ventilation. Wherever he had stopped hanging vent tube, it wasn’t anywhere close to where he was now. The thing that really got me, though, was he was taking a short break sitting on boxes of powder with a cigarette in his hand. It wasn’t the last time I saw a miner doing that, but it scared me something fierce, and I got out of Schultz’s heading as fast as I could get rid of the supplies I was delivering.

The miner I was assigned to, Riordan, was the track drift miner working the opposite shift from Schultz. Track drift miners lengthened the main drift by drilling, blasting, and then laying down rail for the motors to run on. It is an arduous job where some of the strongest, most experienced, and technically proficient miners working at Section 35 could be found.

In addition to drilling and blasting unusually large rounds, track drift miners had to lay the ties and twenty-foot sections of steel rail that the motors ran on. Blasting for track drifts required precision drilling so that the floor was flat enough to lay the ties and rail.

Track drift miners installed various types of ground support for the back and ribs of the drift, hung ventilation tube and water and compressed-air pipelines, and operated the largest mucking and drilling machines in the mine.

Miners working track were paid for the number of feet of progress they made each day. A range of $100–$150 an hour was not unusual.

It was good fortune that I would be getting to work on a track drift as a temporary miner’s helper. It could lead to other things, perhaps even an assignment as a full-time miner’s helper.

One way to quickly get around the mine was to hitch a ride with a motorman as he made his rounds pulling ore or delivering supplies. When I found Bordan by his motor, he told me to hop in a car and he’d take me right to the end of the line where Riordan was.

The ride back to Riordan at the main drift heading, called the face, took about fifteen minutes. Borden stopped the train, and I hopped out of my ore car, thanked him, and started walking toward the end of the track where Riordan was waiting.

Читать дальше