Operation Colosseum

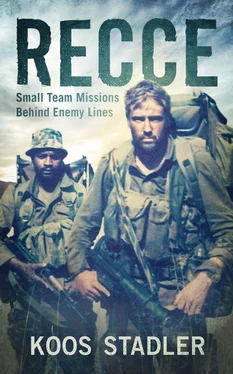

José’s huge frame had earned him the nickname “Mr T”, after the character of BA Baracus in the popular 1980s television action series The A-Team. Depending on the big man’s mood, we would call him “Da Costa” or “Mr T”, or simply by his first name. For Operation Colosseum Mr T became my team buddy, as Vic had to catch up on promotional courses, which every operator still had to complete for promotion, and was subsequently moved to another team.

Da Costa was born in Lobito, then a lively coastal town in the Benguela province of Angola, to a white Portuguese father and a mother from one of the local tribes. Before the Angolan civil war the town had been known for its carnival – not unlike that of Rio de Janeiro – which, together with the town’s location and picturesque setting, attracted many tourists. But his blissful childhood was cut short by the civil war; Da Costa was only eighteen when the war split up his family and forced him and his sister to leave the country.

Over the years Da Costa has shared snippets of his life story and how he came to join Special Forces. I was amazed by what he had experienced by the time he was in his early twenties. It was difficult for me to imagine losing your home and your parents and having to flee for your life at such a young age. What happened to him and his family happened to thousands of other Angolan refugees. Their stories have not received as much attention from the South African media as those of former SADF soldiers, yet their experiences are just as much a part of the Border War story.

In early 1976 Da Costa arrived at Buffalo Base in the Western Caprivi with a group of ex-FNLA soldiers, who would later become the formidable fighting force known as 32 Battalion. Their familes were brought from Rundu and established in the kimbo (village) at Buffalo along the banks of the Kavango River. Da Costa’s first opportunity to do specialised work came with the formation of the reconnaissance wing of 32 Battalion. He joined up, and by the end of 1977 had moved to Omauni, the recce wing’s operational base.

By 1981 he had made up his mind to join Special Forces. Since he had experience in small team work at 32 Battalion Recce Group, he wanted to apply his skills in a specialised environment. He was also under some pressure from his colleagues, because some of the 32 Battalion soldiers were already at 5 Recce, so he and three friends started to prepare. The four of them were transferred from 32 Battalion to Phalaborwa in February 1982. In April they did Special Forces selection with a group of 30 soldiers. Da Costa was one of only six who passed, and was soon transferred to 53 Commando.

At the end of 1984, when the Small Teams commando was established at 5 Recce under the command of then Captain André Diedericks, Da Costa wasted no time in applying, as he believed that, in his own words, he “was destined for greater things”.

Prior to the deployment, Da Costa and I had worked out a programme for the two weeks of rehearsals: PT every morning, and then movement techniques, including patrolling, approach methods, anti-tracking and establishing hides. The PT sessions were a combination of buddy exercises and long-distance running with boots, webbing and weapons. To carry the big man was no mean feat, as he weighed at least 20 kg more than me, but I figured I’d rather get used to it for the day I needed to carry him out of Angola. The buddy-PT with combat gear also ensured that our kit was totally prepared, that there were no loose ends, and that every single item was secured with a string. It also meant that our boots would be worked in and ready for the long trek.

Over the heat of the day we’d prepare equipment – packing rucksacks, testing radios and fine-tuning our personal webbing. The afternoon would be spent planning, preparing maps and working out SOPs for the team, which we jotted down and memorised. Escape and evasion (E&E) plans were discussed and rehearsed in the finest detail.

After dinner we did night-work sessions, going through the same drills as during the morning’s programme. We’d practise the same patrol techniques, but simulate various scenarios in the dark, applying immediate action drills to every contingency. Slowly but surely, Da Costa and I started to blend as a team. We complemented each other in every respect. We would often find ourselves doing the same thing, or following the same course of action, without even having consulted one another.

One morning after our PT session, the ever-pragmatic Da Costa raised the matter of our rucksacks again. If we took the bulky Small Team packs along on the mission, we would not have the immediate advantage of deception when spotted by the enemy. The lightweight “SWAPO” pack, on the other hand, would not be big enough for radios, food and water for seven days, as well as all the optical equipment required for a reconnaissance mission.

Da Costa suggested that we take the big packs and make sure we didn’t move in daytime. The packs could also be cached close to the target when we started the final stalk. In the end we decided to take the Small Team pack, which I was grateful for, as the SWAPO pack didn’t have a frame and could be quite uncomfortable.

When it came to our food and water, we knew that everything would have to be carried, since there was no possibility of a resupply. There would be no cooking, so the gas stoves and cylinders could be discarded. Also no tins – because of their weight. That left us with “zap” [15] Food that was pre-cooked, vacuum-packed and then irradiated at Pelindaba to last for months.

meat, energy bars and peanuts. Vitamin-enriched energy drinks would round off our diet; water would make up easily 70 to 80 per cent of the total weight. Da Costa’s pack weighed in at a relatively modest 80 kg when we were finally ready to deploy.

For a patrol formation during the final approach, I would take the front, with Da Costa carrying the HF radio as usual to my right and slightly back, 20 to 30 metres, depending on the undergrowth and the moon phase. Incidentally, there would be a half-moon during our deployment; this was ideal for an area reconnaissance, as the team would have moonlight for the first half of the night, and no moon during the early morning hours – just what we wanted for a penetration.

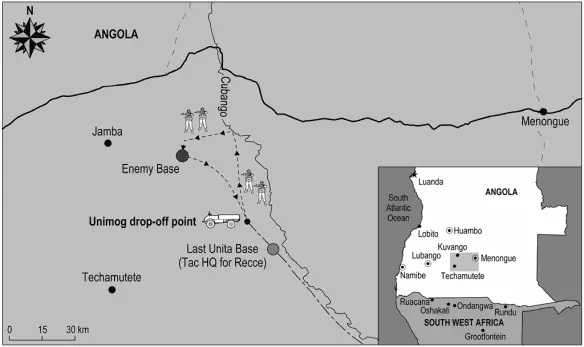

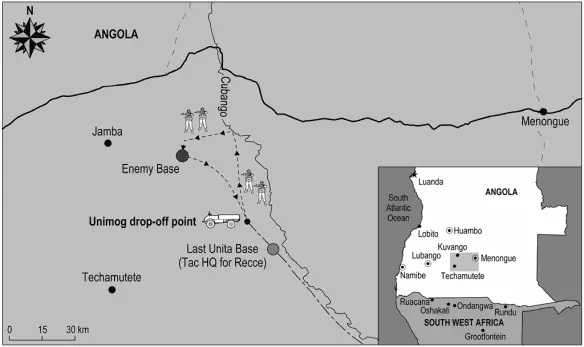

We had to make a final decision on the method of insertion. The combat force would be stationed at a UNITA base approximately 60 km from the target area. From there the reconnaissance team had to infiltrate to an area from where the final recce could be launched. It was decided that a team with three Unimogs would drop us off and return to the main force until it was time for our pick-up.

Contrary to our regular Small Teams procedures, we did not have a dedicated Tac HQ commander and signaller. The team would travel in the HQ grouping under Colonel James Hills, the OC 5 Recce. When deployed, we would talk back to the unit’s signal section at regimental HQ. This was not ideal, as it was standard procedure to have a dedicated comms system – radios, signallers, allocated frequencies and a well-rehearsed no-comms procedure – for the recce team. One certainly did not want to compete for air time when the bullets were inbound.

But Da Costa spent many hours with the HQ signallers, testing frequencies at various distances and talking them through our no-comms procedures. At the time his Afrikaans was limited to “Manne, moenie kak aanjaag nie [Guys, don’t bugger up]”, flavoured with exotic Portuguese swearwords that fortunately only he could understand. In the end he was satisfied, and the national service signalmen developed a grudging respect for the bulky Portuguese.

Читать дальше