4

Operation Caudad

May 1986

IN THE 1980s many rumours had begun to do the rounds about the Recces . Because of the secretive nature of Special Forces training and their operations, little was known about the units. Whatever was written about the Recces in the media was often distorted or misquoted. One Afrikaans magazine in particular had a penchant for stories about the Recces. An article I kept for many years portrayed the South African Special Forces soldier as a silent killing machine, programmed to sneak into enemy bases to slit the guards’ throats prior to an attack. We were depicted as superhuman warriors, fighting the enemies of our country in underhand ways.

Operation Caudad

I experienced first-hand the effect of someone taking these crazy stories too seriously. While on a visit to my folks in Upington, I picked up a lonely hitchhiker close to Vryburg, in what is today the Northern Cape. As soon as the guy got in I sensed from his body odour and scruffy clothes that he was one of the so-called knights of the road, vagrants who travel from town to town, making a living from benefactors and travellers who provide food and drink along the way.

Yet he told me how he studied Agriculture at Stellenbosch University and was travelling back for the start of the new term. After some time he noticed my uniform hanging in the back of the car.

“I also work for the army,” he said, and from the conspiratorial tone of his voice I immediately sensed what was coming.

“Oh, which unit?” I asked innocently.

“You know, I’m not really at liberty to say, but I work for the Recces,” he almost whispered.

“Sorry, I got you wrong there. I thought you were studying at Stellenbosch.”

He had clearly played this game before and was unperturbed. “You see, that’s just a cover. Special Forces have an agreement with the university authorities. Whenever there is a job, I would just disappear one night – and be back two weeks later. No questions asked.”

By now I was starting to enjoy the intriguing tale that was slowly unfolding. “So what are these ‘jobs’ you are called to do?” I asked.

“Don’t you know the Recces? We do the special jobs for the army. Dirty jobs, like silent killing.”

I gave him some more rope: “So how do I sign up for these Recces?”

But apparently he had already summed me up and found me lacking: I was too skinny, too soft-spoken, definitely not Recce material…

“No, they have to approach you . And then you go through a very serious selection.”

He proceeded to give an elaborate explanation of how each candidate is each given a puppy at the beginning of their selection, how they have to nurse the puppy for a year through the training period, and then kill it with their bare hands before they can qualify. He told me how realistic the training was, how trainees would often be killed because every exercise was like “the real thing”. During operations you had to survive on scorpions and snakes, since you could not afford to carry unnecessary items like food.

After about two hours of listening to his heroics, I decided to give him something to really think about. In the middle of nowhere, in the semidesert between Vryburg and Kuruman, I slowed down and pulled into a gravel road off the main road.

I had retrieved my Beretta pistol from under my seat, but kept it from view. “Listen, brother,” I said, “I am an officer with the South African Special Forces, your Recces, and before you ever share your shit with anyone else I’ll just sort you out for good. Get out of my car.”

Then he saw the pistol. And his face went white with fear as he started stuttering, “Sir, please sir, you can’t shoot me. I’m just a poor man.”

In a fraction of a second he had jumped out and retired into the sparse undergrowth. Like a frightened rabbit, he ducked and dived behind the bushes as I got out and pretended to chase him into the veld. He cleared out, no longer the fearless killer of a few minutes before. I dumped his kitbag along the main road and continued on my journey, hoping he had learned his lesson.

I then spent a quiet and restful week with my parents. My father was curious about the Special Forces, so I shared bits of information about selection and training with him, as well as snippets from operations I thought harmless enough. I returned to 5 Recce refreshed and ready to tackle training and preparations with new vigour.

I also got back into the routine of long-distance training and ran every marathon I could, either at Phalaborwa or Pretoria. Zelda and I used every opportunity to spend time together. She often visited Phalaborwa on weekends, and we always found something adventurous to do, either hiking in the mountains at Tzaneen or camping in the game reserves of the Lowveld.

The high command had decided that Small Teams from the other Special Forces units would join forces with Small Teams at 5 Recce. Since all operations were independent, strategic missions, it made sense to bring the teams together to streamline logistics and command and control.

And so three Small Team operators from 1 Recce (Piet Swanepoel, Menno Uys and Jakes Jacobs) moved from Durban to Phalaborwa to join 54 Commando. 4 Recce at Langebaan decided not to commit to the restructuring, since their reconnaissance missions were normally linked to seaborne operations and thus required specialised skills.

With our numbers bolstered, we threw ourselves into our work with a renewed sense of purpose.

By 1986 the ANC was fighting its revolutionary war against the South African government on all fronts: politically through its “hearts-and-minds” campaign and physically, through its armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK). MK had launched a number of incursions into the Northern Transvaal (today Limpopo), while sporadic attacks had been conducted on high-value targets in the interior of the country, like the Church Street bomb in Pretoria on 20 May 1983 and the attack on Magoo’s Bar in Durban on 14 June 1986.

In response to these incursions, the National Party government had formulated a counter-revolutionary war programme that was enforced through a system of close cooperation between government organs and the Defence Force. In addition, the military was tasked to conduct pre-emptive strikes against MK facilities in the so-called frontline states. These were selective precision raids aimed at disrupting ANC structures and discouraging neighbouring countries from harbouring members of the liberation movements.

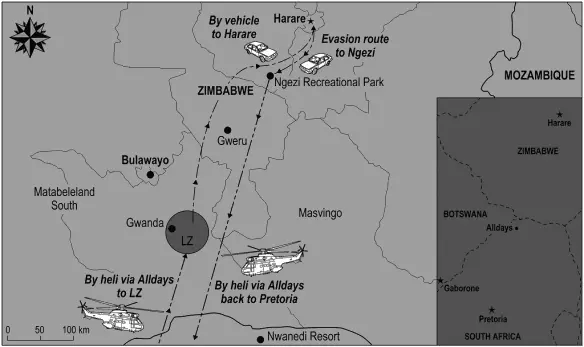

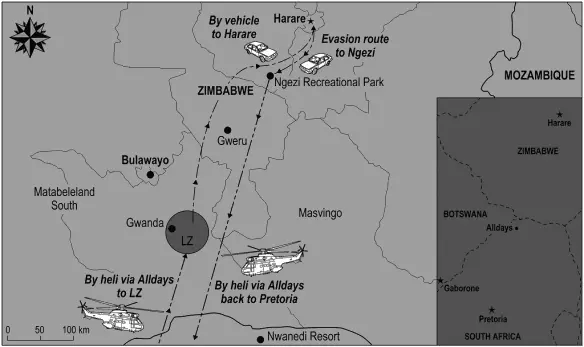

In May 1986 the Defence Force was tasked to conduct strikes against ANC facilities in Harare, Gaborone and Lusaka. The three raids would be conducted simultaneously, so actions had to be coordinated and timings carefully synchronised. While the Lusaka operation was to be an air strike by the SAAF, the Botswana and Zimbabwe raids would be conducted by Special Forces. Because of Harare’s geographic position and the nature of the two targets in the city, the infiltration would be of a clandestine nature. The Gaborone raid would be a helicopter-borne strike launched from South African soil. D-day was determined by the Harare operation, as it was the most challenging of the three deployments and demanded intricate planning.

Diedies was selected as the mission commander for Operation Caudad, the raid on two ANC facilities in Harare. The teams consisted of operators from both Small Teams and 53 Commando. The first target, allocated to Jo-Jo, Vic and a third operator, was a set of ANC offices on the second floor of an office block in Angwa Street in downtown Harare. My team would be led by Bill Pelser, a highly experienced operator from 53 Commando. Our target was a residence, 29 Eves Crescent, in one of Harare’s suburbs, which was used as a transit house for ANC cadres moving to and from South Africa.

Читать дальше