Not all training exercises were as challenging as the one in the Mariepskop area. Once, Small Teams was commandeered to take part in a countrywide exercise run by the Air Force to sharpen their command and control systems and fine-tune the integration of different resources.

Operation Golden Eagle was a typical blue-on-red exercise, with red (“enemy”) bases spread along the eastern border with Mozambique and blue forces based in the interior. A request arrived from Pietersburg Air Force Base for the Recces to do a close-in reconnaissance of red bases at Punda Maria, on the edge of the Kruger National Park. The mission entailed the placement of command-detonated flares to guide bombers to their targets. One flare would be positioned 20 km away to guide the aircraft on their initial run-in, the second 100 m away and the third on the perimeter of the actual target. The jets would detonate the first flare while in the holding area, and the second and third on the approach to the target.

The flare had a separate radio receiver, which was to be connected to the detonator and then armed for action. Little did I know that I was actually testing a new system that would later be used in our reconnaissance missions.

A day before the deployment, Sakkie Sibanda, one of the intelligence NCOs, and I were picked up in a Puma helicopter and taken to Pietersburg. A team of technicians were waiting for us at the base. We went through a quick training session on the flares and tested the systems with the fighter pilots. Just before we departed, Sakkie and I each had a freshly baked pie and a Coke from the Air Force canteen.

The helicopters first took us to a point 20 km east of the target where the first flare would be set up to serve as the initiation point once the air strike came in. I was dropped on a rocky outcrop and had no difficulty in preparing the flare and connecting the receiver while the choppers circled. With the initiation point prepared, Sakkie and I were taken to our respective landing zones (LZs) for the final infiltration to the “enemy” bases, where the target markers would be planted. I was dropped first, just before last light, and started navigating my way through some scattered villages and fields towards the target.

Everything went smoothly. I found the target easily and planted the first flare 100 m out, and the second one at the perimeter fence. I decided to stay put to see how it functioned. Not realising how powerful the explosion would be, I fell asleep right next to the flare, and was rudely awakened by the blast. The “enemy” must have gotten an equal fright, as the huge flame leaped about two storeys into the air. Afterwards they claimed they had located and almost caught me, which was nonsense, as I quickly disappeared into the thick shrubs surrounding the base. The fighter planes came thundering directly over the target in a simulated attack, “bombing” the red base into the proverbial smithereens.

The next morning I exfiltrated and was picked up by the choppers at the prearranged LZ. Mission accomplished.

It was only then that I heard Sakkie didn’t have such a smooth ride to his LZ the day before. The flight engineer told me how, after dropping me, they suddenly got the smell of freshly baked pies. Looking forward past the co-pilot, he tried to locate the bakery.

“You know, Lieutenant,” he said, “I’d never realised you could actually smell a bakery in a chopper. I looked down to see if we could land somewhere to buy a fresh loaf of bread. But the next thing I see are these pieces of what I thought was bird flesh and stuff on the perspex. It was the first time I had seen a bird strike from inside the chopper. So I reached past the co-pilot to see what it was. Then I felt the back of my helmet and it was all wet and sticky – and smelling of fresh pie.”

It turned out that Sakkie had been sitting in the open door of the helicopter until he couldn’t keep his lunch in any longer. But then, as he puked into the rushing wind, everything whirled back inside and into the cockpit. The crew’s helmets were plastered with fresh pie, as was the cabin interior. Since the Air Force crew were not too impressed with the Recces’ performance, we had to buy the drinks during the “debriefing” in the bar that night.

2

Operation Cerberus

September 1985

BY 1985 – my first year as a Small Team operator – the Border War had escalated and SWAPO was aggressively pushing its political agenda while its detachments infiltrated deep into South West Africa. Some of the worst fighting of the war took place in central Ovamboland, while across the border the civil war between the MPLA and UNITA had reached a peak.

Operation Cerberus

The Joint Monitoring Commission (JMC), established in February 1984 under the terms of the Lusaka Accord, consisted of personnel from both the SADF and FAPLA. Its mandate was to monitor the systematic disengagement of the opposing forces in the conflict. After Operation Askari in December 1983, South Africa had indeed withdrawn its forces from Angola. However, SWAPO immediately deployed its fighters into the areas the SADF had evacuated, violating the terms of the disengagement agreement. Since the JMC could not fulfil its mandate, it soon became dysfunctional.

Then Wynand du Toit from 4 Recce was captured and two of his teammates, Louis van Breda and Rowland Liebenberg, were killed during a Special Forces raid on a Gulf Oil installation in the Cabinda enclave of Angola. Politically this was a disaster for South Africa, as the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pik Botha, had just proclaimed that all SADF troops had been withdrawn from Angola. The MPLA of course exploited the situation and accused the South African government of being liars who could not be trusted in any peace negotiations. Following the failure of the JMC, the SADF moved its forces back across the border into Angola, launching attacks on bases SWAPO had established.

It was against this backdrop of political turmoil and strategic manoeuvring that I was sent on my first mission with 5 Recce’s Small Teams. One evening in July, after we had gathered at the block for a night training session, Diedies called three teams into the intelligence briefing room. Dave Drew, by then the unit’s intelligence officer, was also there, along with Eric McNelly, a counterintelligence officer from Special Forces HQ in Pretoria. We knew immediately something was up.

First we got the usual counterintelligence brief from McNelly: that the enemy was out there listening and that we should keep our traps shut. We had heard this message often without fully comprehending the reality of the threat. The need for secrecy was only brought home a year later when Major André Pienaar from Special Forces HQ was caught spying for “an African country”. He was arrested at Jan Smuts airport (today OR Tambo International) when he tried to travel to Zimbabwe with seven top-secret files from Military Intelligence. Pienaar had been working in none other than the counterintelligence section, which had to keep us in check, and as such was privy to all the information regarding Special Forces deployments. (Pienaar remained in custody and was only released in the early 1990s.)

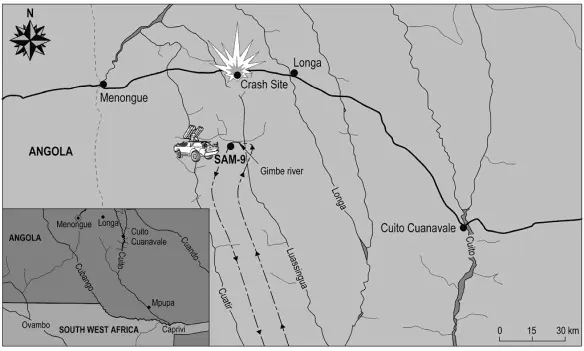

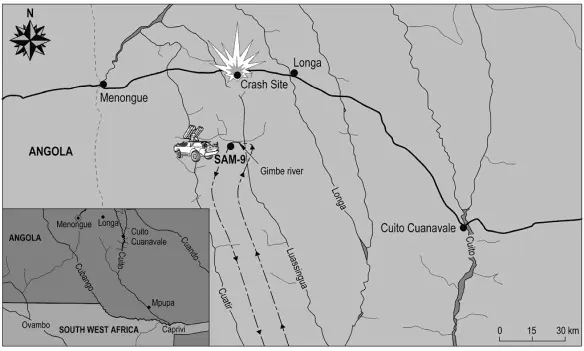

Dave Drew first gave us an overview of air traffic between Lubango and Cuito Cuanavale in southern Angola. Since the railway line running east from Lubango to Menongue had been rendered useless by UNITA, the MPLA was now relying heavily on air transport to get their logistics to the front. Daily flights of Soviet Antonov cargo planes transported huge amounts of logistics and troops to Menongue in support of the MPLA war effort. SWAPO’s Eastern Front also benefited substantially from this, as their logistics were ferried by truck from Menongue to their base southwest of the town – an area I would get to know intimately during later deployments.

Читать дальше