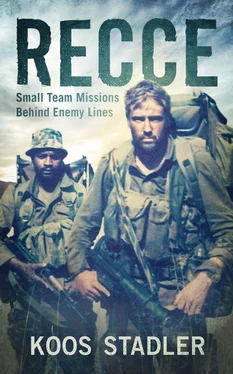

Diedies and I were the only two living-in officers in Small Teams and we clicked immediately. He lived up to everything I had heard about him. The eternal optimist, Diedies was unstoppable when a new challenge presented itself. Every minute of each day he was busy working out new schemes, thinking of ways to outwit the enemy, inventing new tricks and planning new operations. He also felt a great sense of responsibility towards his comrades and subordinates, and would not expect anything of them he wouldn’t do himself. His outstanding leadership qualities have always served as inspiration for me. But it wasn’t until I had the opportunity to deploy with him that I realised why he was such an outstanding soldier.

Commandant Boet Swart, 5 Recce’s second-in-command, also lived with us in the mess. Soon a close camaraderie developed, as the three of us shared the same interests. Every morning at 05:00 I was kicked out of bed by the old man. I then had to make coffee and serve him and Diedies in bed. “Oom Boet” as he was affectionately called, was a delightful individual, with a fine sense of humour and contagious enthusiasm. He was also a highly professional soldier, having served in various units in the then Rhodesia. Boet was also the best Tac HQ commander I ever came across.

Initially we were four two-man teams. Diedies and his long-time buddy from many previous deployments, Neves Thomas Matias, formed the first team. The others consisted of Lieutenant Jo-Jo Bruyns and José da Costa, Paul Dobe (“Americo”) and José dos Santos, and me and CC Victorino. While Da Costa, Dos Santos, Americo and Victorino were by then South African citizens, they all hailed from Angola, having served with the FNLA during the civil war. They later joined 32 Battalion in the Caprivi until they volunteered for Special Forces selection.

These guys – all experienced soldiers – formed the backbone of the Small Team capability at the time. They were all Portuguese-speaking, strong-willed, motivated and highly capable, and had joined Small Teams of their own free will. During my five years with Small Teams the group remained relatively small and contained. We never had more than six teams at a time.

This period saw a number of people coming and going again. Mike Mushayi, along with two other ex-Rhodesian soldiers, also joined Small Teams then. Not all operators were cut out for Small Teams, as they not only had to cope with the demands of a rigorous routine while on the base but also had to manage the stresses that came with deployment in small groups. The base routine was taxing, and the months away from home, either on rehearsals or actual deployments, would place great strain on the family life of a married operator.

Our first exposure to the joys of Small Team ops was a training exercise in the Mariepskop area, at the northernmost tip of the Drakensberg range. Diedies, Dave Scales and Corné Vermaak, the intelligence officer dedicated to Small Teams, were to run the Tac HQ, while two teams deployed in the most rugged and thickly vegetated terrain imaginable – the steep mountains and deep valleys of the Blyde River Canyon.

The exercise was cleverly worked out around a scenario whereby ANC insurgents had infiltrated the area from Mozambique and established weapons caches in the secluded valleys, utilising donkey trains to transport their goods. The intelligence picture was indeed based on fact, although the teams never knew exactly how much was fact and how much fiction. We expected to encounter enemy at any time during the deployment.

At first I did not realise the significance of this first deployment, but it dawned on me much later that Diedies was already preparing us for deployments in the mountainous terrain around the town of Lubango in southwestern Angola – an area that would become the focus of Small Team deployments in years to come.

For some reason I didn’t fare well on that exercise, and felt like a complete failure afterwards. Vic was a strong man, and I had to work hard to keep up. Down in the valleys the vegetation was subtropical, virtually impenetrable. The first night we spent eight hours in the pitch darkness to cover 700 m, trying desperately to crawl through the undergrowth with our huge, heavy packs. It was literally a matter of one step forward, three steps back – as the frames of the packs got tangled in the vines and roots.

I struggled to master the new challenges of comms procedure, one-time letter pads and Morse code. Our comms with Dave were mostly poor – partly due to the deep ravines we were deployed in, but also because we were inexperienced and not well prepared. At some point Vic and I had a difference of opinion about the position of our observation post (OP), which we would use to watch a cave supposed to be one of the targets. Then we argued about the best route to take. Having studied the map, I insisted that we go up a dry waterfall during our exfiltration. But when I took a nasty fall while attempting to scale the almost vertical cliff, I realised my mistake. Luckily I fell directly backwards onto my pack. Mildly concussed, I tried to stand up. Vic quietly walked up to me, lifted my pack and pulled me to my feet. Then we followed the route he had suggested from the beginning.

As could be expected, the debrief at the Tac HQ on Mariepskop was not a positive or rewarding experience. Diedies pointed out our navigational errors, poor choices of OP sites and a number of tactical mistakes. Dave was not at all happy with the standard of our comms, particularly the fact that we were repeatedly late with scheduled or “scheds”, as well as the poor quality of our Morse.

Driving back with Diedies from Mariepskop to the unit at Phalaborwa I fell quiet. Eventually Diedies broke the silence:

“What’s the matter?”

“I don’t know,” I said, “but I think I messed up.”

He was wise enough not to take the matter any further and simply said, “Sleep on it tonight and we’ll talk tomorrow.”

By the next morning I felt significantly better. I realised that, while the other guys had been with Small Teams much longer than I had, they hadn’t fared substantially better on the exercise. What I needed to do was to cover a few basics and master the technical challenges that were new to me.

So Vic and I got stuck into a serious learning routine. We spent hours sending and receiving Morse, as well as improving our radio work, incorporating field repairs, the use of various types of antennae and ECM/ECCM procedures. Knowledge of enemy weapons, aircraft and vehicles turned into a bit of a status symbol among the teams and we had daily slideshow competitions to test each other’s knowledge.

We also meticulously prepared our equipment and were fortunate to have at our disposal the services of Sergeant Major “Whalla-whalla” van Rensburg, the unit’s tailor. With his heavy-duty sewing machines, Whalla-whalla could redesign any piece of webbing and turn it into a masterpiece. The result was chest-webbing and kidney pouches designed to our own taste, with a special pouch for each item of survival kit, strobe light, cutting pliers, torch or whatever else the operator considered vital enough to keep on his chest. Whalla-whalla also made canvas and cloth bags for just about everything, from toilet paper to peanuts. The much-treasured “Whalla-whalla bag” soon became a hallmark of Small Teams.

In addition to the rigorous training, we used the time at base to brush up on our first-aid skills. We’d set aside a week for the unit doctor to guide us through the ABCs of resuscitation, the contents and application of the priority 1 and 2 medical packs, improvised techniques for applying slings and how to stop bleeding. A casualty scenario was built into each exercise, with the result that we ended up punching each other (and ourselves!) full of needle holes in an attempt to get a drip flowing. I became quite adept at administering a drip to myself, even with the sweat running and the adrenaline pumping.

Читать дальше