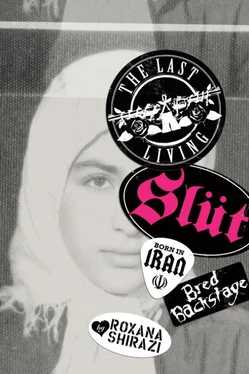

The man had come to stay. It was late, and I larked about as usual. We ate dinner by a gas lamp around the sofreh with my uncles, who had also been released from prison. Suddenly the new man stood up and began barking orders at me as he pushed me into the adjacent room. “You’re not allowed food until you shut up,” he shouted. My mother said nothing. I didn’t know this man; I had no idea who he was or why he was screaming at me. I clasped my hands to my ears to block out his yelling. Tears flooded my face.

“Come on, soldiers! Come and take this bad man back to prison,” I yelled through my sobs until my voice splintered. “He’s a bad man. He’s hurting me.” I kept sobbing and yelling, hoping the savak would come take him away. But they never did; I was forced to put up with him and his ways for years to come.

Shortly after that night, the man became my new father. He came with grisly relics of torture, hacked and carved into his body by the prison guards who tried to force him to snitch on his friends. I touched the dents and deep cavities on his wrists and ran my fingers along the zigzag scars on his back, fascinated by the tunnels etched on his flesh.

“Darling, leave your father alone!” my grandmother would scold as she prepared delicious dishes for the new head of the house.

“And stop calling him by his name,” she whispered to me later that night, after hearing me use his first name, Saeed. “You must call him Dad now.”

Dad, Dad, Dad . As I went to sleep that night, I rolled the word over in my brain as if I were learning some new language. I felt like a normal girl now that I had a proper dad at home. We were a real family. My mother had finally found someone who was just as politically motivated as she was. I was happy for her—even though he scared me with his sudden mood swings and chilling cries at night, when flashbacks of prison torture invaded his dreams.

Soon, he and my mother were leaving regularly to march in the streets with thousands of others to fight the Shah’s terrible regime and start a new Iran. I found myself nestling constantly in my grandmother’s vast warm lap or laying on the lush carpets by the clunky heater, praying they would return alive.

With my new dad came a whole new set of cousins, aunties, and a sea of ready-made faces who were now my family. One of these was a silver-haired granddaddy who taught me the Qur’an and the ritual of Namaz (prayer) so thoroughly that I felt a new holiness and purity take over my soul. I prayed three times a day without fail, reading from the Qur’an loudly and lovingly. Fasting during Ramadan became a holy sweet experience. Arising at dawn to pray, I felt closer to God and all beautiful things. I knew God loved me even though I did naughty things in private.

My new granddaddy was wonderful and kind. He was my first real experience with a father figure, and I loved listening to his wise tales and guidance. When he instructed me to recite passages from the Qur’an, my whole being felt complete.

I would also sit and watch him smoke opium. He’d hold a square metal container. Inside were hot coals and little black bits that looked like buttons, which he would melt on the coals. He’d bring a ceramic pipe to his lips. The sweet, pungent perfume hissed at my nose and smooched my lips as the luscious aroma enveloped me. I’d feel hypnotized, as if I were floating through a thick, smoky curtain into an Arabian fairy tale.

Finally, on a dull winter day in January 1979, the moment everyone was waiting for arrived. I stood on the doorstep and listened to the cars honking, the people singing jubilantly in the streets. Slushy snow capped the pavements like moldering cake, but the air was spiked with euphoria. I walked the streets with my mum and stepdad’s friends and jubilantly belted victory songs about working-class people united against a dictator who bled the poor dry. I worried about the state of the world and whether our new leader, this kind-looking, bearded old man called Khomeini, would make people happier.

After the fall of the Shah, our little family moved to a block of apartments that was a ten-minute walk from my grandmother’s house. There was a fig tree in the garden, and many new friends nearby for me to play with. The apartment block was in a small alley with a maidoon at the end.

When I found out that the new regime forbade mixing boys and girls in school, I was peeved about not getting to go with my boy cousins and threw one of my spoiled brat tantrums.

The new leader of the country, Khomeini, was the supreme spiritual leader whose word overruled everything. The people of Iran had just started to breathe a sigh of relief after ridding the country of one tyrannical regime when Khomeini announced a system of governance called Velayat-e faqih based on the rules of Islam formulated by himself and other clerics.

Anyone opposing this was considered to be against Islam and was punished accordingly. It became compulsory for women to cover their hair and bodies. Makeup, nail varnish, perfume, ties, and cologne were seen as Western symbols, and wearing them was considered counterrevolutionary and subject to severe punishment. Denying Islam was punishable by death. Adulterers were stoned. Those who had sex outside of marriage incurred lashes. Thieves, if caught, would likely lose their right hand and left foot. Women were required to get permission from either their father or husband for almost every activity. And since the sexes were not allowed to mix, all public spaces, including buses and offices, were segregated. Even dancing was forbidden.

This climate of fear continued to accelerate quickly. Pasdar , the armed revolutionary guards, and the Komiteh (the morality police patrolling the streets) punished anyone they wanted. Violence toward women who flashed just a strand of hair or a speck of makeup became common. I had to wear a roosarie (head scarf) and a somber montoe (a long black robe) over my clothes. I was lost in heaps of fabric; apart from my face, every inch of my skin drowned in thick cloth.

“We’ve gone from bad to worse,” I’d hear my mum tell my grandmother in a somber whisper, as if there might be covert spies for Khomeini among our neighbors. “God, when is our country going to be free?”

Every morning at school, we lined up to display our fingernails to the head teachers, then bowed our heads and recited from the Qur’an in rhythmic unison. I found the prayer hypnotic and soothing. In the afternoons, I devoured my class work: math, science, and literature. The hard work paid off and I achieved straight As in every subject at school. The head teacher gave me flowers and my family fawned over me. “She has a unique beauty, and so intelligent, too,” my aunts would nudge my mother, gathering around to observe me like some rare plant. “She will definitely find a nice husband.”

I spent my free time in the alley, reading fairy tales and talking about boys with Soraya and Zari, my dearest friends in the world, who were like sisters to me. Together, we ruled the neighborhood. The other girls followed us, hanging on our every word. When they gushed, “You are a princess, like Cinderella,” my heart swelled full of love.

My new dad ditched his job as a cab driver and started a construction company, where he made much more money. Soon he took us to gorgeous uptown restaurants and bought me prettier clothes, which I enjoyed showing off.

I lusted after the boys who lived nearby—many of them streetwise, bad-boy types. I would strut down the street in my platform shoes, ambling around the corner where they hung out. Though I acted innocent and unaware of their gaze, I’d slide my head scarf back just so, revealing my pearl hair clips. And I’d unbutton my montoe slightly, sauntering right past the Pasdar stationed at the end of our street. My friends watched from the windows, giggling nervously at what was either my extreme bravery or stupidity.

Читать дальше