Joanna Kavenna

The Ice Museum: In Search of the Lost Land of Thule

Joanna Kavenna has worked for The New York Review of Books , The Observer , the Daily Telegraph , The London Review of Books , The Guardian , and The Times Literary Supplement , among other publications. She currently holds a writing fellowship at St. John’s College, Cambridge.

The Ice Museum: In Search of the Lost Land of Thule

For my parents

and B. H. D. M.

with love

. . . ONLY THE PAST IS IMMORTAL.

DECIDE TO TAKE A TRIP, READ BOOKS OF TRAVEL

GO QUICKLY! EVEN SOCRATES IS MORTAL

MENTION THE NAME OF HAPPINESS: IT IS

ATLANTIS, ULTIMA THULE, OR THE LIMELIGHT,

CATHAY OR HEAVEN. BUT GO QUICKLY . . .

“PERSONAE,” DELMORE SCHWARTZ (1913-1966)

Seen from above, the ice sounds a ceaseless warning. A vicious blankness emanates from the white expanse below. The shadow of the plane falls on fleeting clouds. The ice smothers forests and mountains under a thick pall. Nothing moves across the whiteness.

The plane is drifting downwards, falling towards the glazed countryside. The ice is a vista of emptiness, like a paradox, a symbol expressing the inexpressible; here is the vivid realization of absence. As the plane descends, the warning sounds insistently: LEAVE. A single syllable resounding across the smothered land. No point in coming here. The country is closed for the ice deluge, to be opened in the spring. The plane is plunging through a white sky, into banks of drifting cloud. The trees below are bleached, their branches bent under the weight of the snow. As the plane skids across the runway the trees blur into lines of whiteness.

Shaking their heads, the passengers disembark. A pale sun shines onto the rigid arms of the trees. I step slowly onto the frost-coated runway. A thick wind blasts at my body, forcing me to bend against it. A woman is signalling frantically, pointing at a bus. We all board, obediently.

In this icy landscape, it is hard to discern distance and gradient. Complex layers of vegetation are simplified into one dense line of thick snow-bound forest. Only the most violent features of the landscape remain—the most jagged and stark. Trees seem to be locked in the ice, bowed by the weight of their casing, like statues struggling to become free of a block of stone. The sun trembles above the horizon, casting squat shadows on the snow, waiting to sink into darkness again. It is a landscape ripe for fantastical embellishment; the silence invites it. Something about the brute simplicity of the nature outside—cold, white, blank—sends me into thoughts of the remote and atavistic—stumbling monsters, shambling old trolls, vast footprints in the snow.

Under the snow, the ice land is an anonymous world, the trees stripped of colour. The frost breath of the wind makes me blink, the frigid air rips at my lungs. The fjord is frozen, the trees are silver splinters.

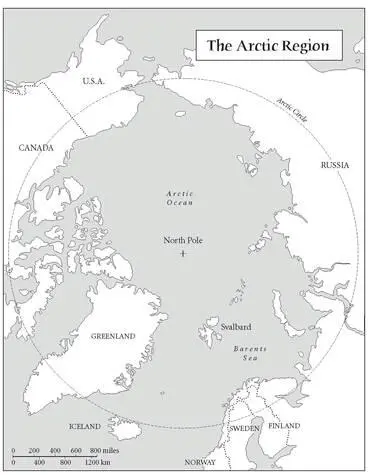

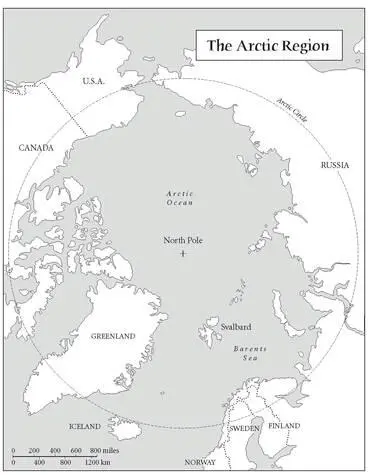

I was travelling through northern lands, compelled by the endless indeterminacy of a myth: the land of Thule—the most northerly place in the ancient world. Before the regions north of Britain were mapped, there was a dream of a silent place, where the inhabitants lived under darkened skies through the winter, and enjoyed constant sunshine in the summer. A land near a frozen ocean, draped in mist. Thule was seen once, described in opaque prose, and never identified with any certainty again. It became a mystery land, standing by a cold sea. A land at the edge of the maps.

A Greek explorer, Pytheas, began the story: he claimed to have reached Thule in the fourth century B.C. He had sailed from the sun-drenched city of Marseilles to Britain. He sailed up to the north of Scotland, and then sailed onwards for about six days into the remote reaches of the ocean, until he sighted a land called Thule. There, so the story goes, the inhabitants showed him where the sun set on the shortest day. In the winter, the land was plunged into darkness. Near Thule, the sea began to thicken, and Pytheas saw the sea, sky and land merging into a viscous mass, rising and falling with the motion of the waves. He turned away from the seething semi-solid ocean, and sailed back to Marseilles.

Where was Thule? The question perplexed the ancient geographers, as they fashioned their fantastical maps—imagining the known world encircled by an impassable river, or crisscrossed by vast belts of water from Pole to Pole and around the equator. There were contenders throughout history—Iceland, Scandinavia, Britain—but the precise location of Thule was never categorically determined. Thule remained a mystery—an island, shrouded in a mist, standing on the edge of a frozen ocean.

Pliny the Elder described Thule as the ‘most remote of all those lands recorded,’ a place where ‘there are no nights at midsummer when the sun is passing through the sign of the Crab, and on the other hand no days at midwinter, indeed some writers think this is the case for periods of six months at a time without a break.’ Virgil called it Ultima Thule—farthest Thule—emphasizing its remoteness, its status as the shadowy last country of the northern world. Strabo poured scorn on the idea. Pytheas—a charlatan, wrote Strabo—had made up a load of fiction about the north, and Thule was just one among the mass of lies and fables he had spun. He had said that Thule was six days’ sail north of Britain, which was absolutely impossible, Strabo insisted. It was obvious that Britain was the most northerly inhabited land in the world, a place where the inhabitants lived in misery because of the cold. Only Ireland was more miserable, Strabo thought, where everyone lay with their sisters and ate their parents.

With each new discovery in the north the name of Thule was evoked. The Romans reached the north of Britain, and claimed they had conquered Thule. The scholar Procopius thought Thule was in Scandinavia, and wrote garbled anthropologies of the Thulitae, the inhabitants of the vast country of Thule. In search of a retreat, clerics from early medieval Ireland sailed to Iceland—a land they thought was Thule—and brought back stories of a place where hermits clung to sea-lashed rocks, and cried for the forgiveness of their God. The Venerable Bede called Iceland Thule, as did King Alfred of England. The medieval German poem “Meregarto” described Thule as a place where the sun never shone, and the ice became as hard as crystal, so the inhabitants could ‘make a fire above it, till the crystal glows.’ Petrarch mused on where it might be; the cartographer Mercator fixed Thule at Iceland. Christopher Columbus claimed he had been there, long before he arrived in America. As the lands of the north were mapped—Iceland, Scandinavia, Britain, Greenland, the Baltic coast—the name of Thule was moved around, from Iceland to Norway, from northern Britain to the tip of Greenland. Northerly latitude was enough, a midnight sun and a frozen ocean still more persuasive.

Ultima Thule, distant island, place of dreams, but disconcerting and somehow strange—writers flung the words into their verse and prose, drawing on their resonance. A few scholars tried to find the solution in the meaning of the word “Thule,” stacking up their definitions, squabbling about Old Norse and Phoenician meanings. Some said Thule might have come from the Old Norse for frozen earth or tree or from the Old Irish for silent or from the Old Saxon for limit or from the Arabic for far off. But no one could decide for certain; eventually most seemed to agree that the origin of the word was unknown. The spelling of Thule was inconsistent through the ages: Thule, Thulé, Thula, Thyle, Thile, Thila, Tyle, Tila, Tylen and Tilla, among others. Faced with the subject of the pronunciation of Thule, the scholars shrugged their shoulders. Some said ‘Toolay,’ some said ‘Thoolay,’ a very few said ‘Thool.’ Poets rhymed Thule with newly, truly and unruly, but never, it seemed, with drool.

Читать дальше