Of course there is always the older groupie mafia, whose compulsory sedate demeanor nevertheless reeks of a still-rabid desire to get them some rocker meat for the night. They hang around, defeated and heavier, packed into denim. They have sucked and chewed, fucked and crashed their way through all the other sleaze hair rockers of the ’80s that were spawned by Mötley Crüe. They went on actual dates with them before they were married and divorced and married again. They have the original stories of broken hearts, and the hazy bloated memories and scars to prove them. Their sallow bodies are awash in whiskey and sperm. The flickering light catches the hard lines on their faces. At forty-something years old, they’re desperate, angry, ready to push these younger girls outta the way. Without this world, they would be nothing. This is their identity.

The older boys are always at the front, with sagging tattoos and hackneyed talk of the good old days. They want to catch the shit hitting them in the face, the head, whatever. It takes them away that much from their two-by-fours and kids’ packed lunches and PTA meetings. Their once-long hair is now in violent retreat. But they saw it all: the Pistols, Sabbath, the Sweet, the rest. They saw the blood, the shit, the razors and needles, the vomit, the pretty little chickens. This is beautiful, like their morning wood at fourteen and the spotty teenage-boy need for getting laid that came with it. They know all the songs and try to make every gig. The cash they spend on seeing bands is supposed to be milk money for their children, but this is their life, their blood, their every happiness. Just like me. Because rock ‘n’ roll is my type O.

When all your thoughts and emotions are consumed by rock ‘n’ roll and all your actions are dependent on the movements of a rock band, then your life becomes like that of a junkie. The blood that rushes through your veins, the breath that catches your throat, your tears, your cash, your enormous love, your brainwaves, your perfume, your orgasms… everything. Everything. But it’s all an illusion: the love you feel so passionately, the bond of friendship, the endless hotel rooms, the emotional support you give and take, the food you eat, your guttural hollers of ecstasy, your jealousy, your thirst. The exhaustion and the cold and the heat, the heels that swat your skin, the condoms you use and don’t use, the STD tests, the locked jaw. It is a high, a new realm, a space you can enter without warning or awareness. And it can become your pulse, permeate your genetic makeup. This I know.

When it does, suddenly all the decisions you make are not entirely yours. And you don’t know how it happened. You have little control over your emotions and actions. And it’s all because of a rock-and-roll band.

This is my life.

Gottfried Helnwein: Beautiful Victim

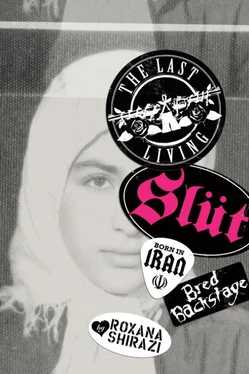

I was a Child Basked in Gunfire, Islamic Law and Sexuality

Iwas born in a military hospital in Tehran, Iran. My mother was a twenty-four-year-old political activist who’d chosen the Russian-run hospital as a nod to socialism, the political movement she’d aligned herself with in her resistance to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s regime. I was born into a totalitarian society with little social and political freedom, where only the Shah and the ruling elite benefited from the country’s wealth while ordinary people didn’t have access to decent health care and education.

As soon as her belly swelled, my mother knew I was going to be a girl. She just didn’t know how naughty I was going to be. When her water broke, my eighteen-year-old aunt proudly accompanied her to the hospital. Once inside, my mother learned that the hospital’s sanitized and celebrated reputation was a sham: it was an institution of clinical cruelty. My mother was in labor for sixteen hours—my head was so big that I couldn’t easily come out—but labor drugs were strictly against hospital policy, regardless of the situation. Instead, the nurses believed in discipline, so they slapped and kicked my mother to make her push harder. They screamed and shouted at her to get on with it. A fine mist of blood rose on the veins of my mum’s milk-white neck. At one point during the ordeal, my mum thought about running out of there with me still inside her. But before she could, she passed out on the table.

I was born in the early hours of the morning. The nurses whisked me away to prevent physical contact with my mother, which was also against hospital policy. They left her alone, lying on the operating table in the vacant room without water for three hours. Unable to get up, she resorted to licking droplets of sweat from her face.

Every day for a week, the nurses brought me to my mother for five minutes of breastfeeding, convinced that their military regimen was for the good of the patient.

A few weeks after I was born, my eighteen-year-old aunt and uncle were arrested, tortured, and interrogated for being anti-Shah activists. From that day until the revolution in 1979, various friends and members of my mother’s family were constantly getting arrested for their political beliefs and activities. My mother and I made countless trips to Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison to catch a glimpse of them behind bars.

My first childhood home belonged to my grandmother, Anneh. It was there, in the middle of Iran’s revolution and the subsequent war with Iraq, that I remained, basked in pure love and happiness during the terror of revolutionary gunfire, Islamic law, and my initiation into sexuality.

Iwas six months old when I went to prison with my mum. It was only for twenty-four hours, but it was enough to affect her for a long time.

My grandmother, my mum, and I were at home one afternoon when the savak, the Shah’s secret police, broke down the door. There were four or five of them. I was in my mum’s arms as she watched them break and tear everything apart in my grandmother’s house, looking for leaflets, literature, books, and any other anti-Shah paraphernalia that would prove my mother was a political activist. My mum’s face was sheet-white. I screamed while my grandmother prayed in the corner.

“Get up. You’re coming with us,” the men barked at my mum.

Though she obeyed, she insisted that she had to bring me, my nappies, and my milk bottle. They marched her, with me in her arms, to a car waiting outside and sat on either side of us as they drove to Komiteh Moshtarak Zed-e-Kharaabkaari Prison, used by the savak for interrogation. Once inside the prison, my mum was blindfolded and led along a hallway, still carrying me. When they took off her blindfold, she saw that she was in a small room. They left her there overnight, where she watched me sleep as she awaited her fate.

The next morning, she was taken to an interrogation room and I was handed to the guards. She was petrified that she’d be raped, tortured, and killed, and there’d be no one left to take care of my grandmother and me. Fortunately, the interrogator was lenient. He questioned my mum about her and her brothers’ political activities. She must have convinced him she didn’t know anything, because suddenly he snapped at her to get out. She grabbed me from the guards, ran out, and found a taxi to take us to the safety of our home.

I led a fairy-tale existence in the sunshine-soaked dusty back alleys of Narmak, a small, up-and-coming lower-middle-class neighborhood in northeast Tehran. I played day and night in the alley outside my grandmother’s ancient two-story house.

Читать дальше