After 1945, Jünger would explore the posthistorical mood of a dissolved occident, that old Enlightened Europe that reached a zenith of development just as it destroyed itself in the process. If every document of civilization is at the same time a document of barbarism, as Walter Benjamin famously observed, then the World War II chronicles of Ernst Jünger are surely one of the brightest and most enduring testaments to that Janus-faced history.

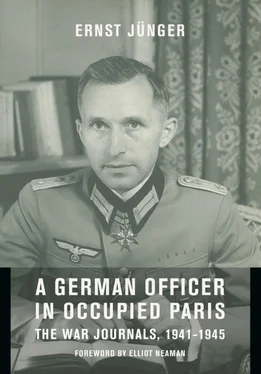

English-speaking readers who seek access to Ernst Jünger’s works have a long tradition of translations to explore. Over a dozen of his titles have appeared in English since 1929. In Stahlgewittern ( Storm of Steel ), his World War I memoir and probably his most famous book, has been translated twice into English and received serious attention from readers and critics alike. Four of Jünger’s six World War II journals, on the other hand, are presented here in English in their entirety for the first time. These texts first appeared in German in 1949 collected under the title Strahlungen , which is roughly equivalent to the English for “rays, “beams,” (of light), “radiations,” or “emanations.”

In his original preface Jünger explains the concept behind this title as the combination of themes that radiate across historical events to illuminate the mind of the observer like waves of light and dark patterns fluctuating with the extremes of existence. To the dark sphere belong the horrors of war and destruction; the realm of light encompasses moments of love, family, nature, and art to uplift and guide us. Jünger imagined his journals capturing such emanations and reflecting them back to the reader. He conceived of this interplay as a decidedly moral—not to say metaphysical—dynamic that epitomizes the function of art, which conveys a lesson couched in words and parables that challenge the reader to fathom through careful, disciplined reading. Indeed, for Jünger this reading process represents an almost sacred duty. In the tradition of the romantic poet, he endows his texts with spiritual value and his literary mission with the promise of salvation: whosoever shall read these words and experience excitement of the will or of the emotions, shall be granted insight into the core of the message.

The personal reflections in these four journals are based on the definitive German edition of Jünger’s works and cover the period when he joins the staff at military headquarters in Paris in February 1941 at the rank of captain, and continue through the events when he and his family endure Allied bombing raids on their village beginning in 1944. Finally, he records the effect of witnessing American tank divisions roll through his damaged town on their eastward course in the spring of 1945.

Ernst Jünger’s journals are remarkable for several reasons, but chiefly because he was an articulate observer of life and nature whose diaries record three historical areas of experience. The first of these is at the personal and cultural core of the two separate Paris journals, which detail his interaction with the French people, particularly writers, artists, and other figures who attached themselves to the German cause during the occupation. Those entries document his genuine Francophile excitement at the beauties and secrets of the city as well as his lightly disguised romantic affairs during this tour of duty. We also watch him interacting with his comrades, other officers who are carrying out their administrative duties and frequently discussing political opinions with him. Such material is, in fact, most revealing when it places him on the fringe of the group of Wehrmacht conspirators plotting to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944, a group he may have inspired but declined to join.

The second area of historical importance comprises first-hand experiences from Jünger’s interlude on the eastern front. His brief tour of duty covered in Notes from the Caucasus describes a risky posting in hostile, mountainous territory at the moment when German forces are beginning their retreat in the face of the Russian victory at Stalingrad. Here he witnesses the chaos and horror of a routed army and the suffering of its soldiers, though he is also always completely candid about the torment perpetrated by his own compatriots.

The third area of historical and human interest covered in these journals records what it was like to experience the allied bombings of German cities, particularly of Hannover and its outlying villages. He had spent his childhood in Hannover and in 1939 moved back to the region, settling in the village of Kirchhorst, fifteen kilometers to the northeast of the city. He had witnessed aerial bombing raids on Paris from the spring of 1943 onwards, but always from a safe distance. After the German retreat from Paris, he reaches Kirchhorst in September 1944 where he is no longer the detached observer enjoying a position of power and capable of finding appealing traces of grandeur in carnage. Rather, he is a reduced to the role of threatened civilian struggling to protect his family and several refugees as they prepare for the inevitable capitulation.

In addition to documenting topical events, Jünger’s journals also record the inner life of the man. He was a voracious reader, a prolific writer, a passionate entomologist, and a thinker given to mystical speculation who also suffered occasionally from depression. As a result, these journals are filled with notes on reading that record his subjective responses to French, Russian, English, and American writers, both classical and contemporary. They chronicle his musings and his intellectual growth—and closely related—his avid book collecting activity among the antiquarian booksellers of Paris. As he reads, he frequently takes issue with the thought processes of the writers who fascinate him. These often stimulate his personal brand of mysticism regarding the nature of the cosmos and the relationship of man to God. After finishing his first reading of the Bible, he begins again, this time consulting scholarly commentary to explicate the texts. These traditions reinforce his own piety and encourage mystical and mythically tinged speculation about history, linguistics, and science. In fact, this restless and deeply irrational aspect of Jünger’s mind conflicts with his scientific training to the extent that piety ultimately motivates a skeptical rejection of Darwin that sounds quaint today.

Science, however, is always central to Jünger’s activity and world view. In 1923 he began to study zoology and philosophy in Leipzig, and although he abandoned his studies to concentrate on writing, his life-long passion for insects—especially collecting beetles—never waned. These journals detail how his curiosity about nature provides both a respite from human company and a glimpse of creation in a microcosm. Jünger’s aesthetic appreciation of nature—for example, the exhilaration he finds in the rich iridescence of a dung beetle’s carapace—is essentially the same reflexive aesthetic he records at the sight of a bomber squadron at sunset. His next stage of reflective thought, however, quickly juxtaposes the first impression with the reality of mechanized death.

The literary style of these journals—particularly of this translation—requires a few remarks. Readers of Jünger sometimes become impatient when they perceive a putative coldness, apparent distance, or lack of emotional engagement with people and events. This objective detachment in his style correlates with the principles of the man himself. The cool, sometime impersonal tone of many journal entries are devices to maintain the rhetorical defenses of a military man trained to endure hardship with stoic discipline and respond to the world with strict categories. Such training can color many facets of life, not just those moments that demand endurance. Jünger’s laconic notations may strike some readers as callous in situations when sentiment might seem more fitting. Yet Jünger preferred not to commit too much sentiment to his journal, which he conceived as a manuscript for public consumption and not as a therapeutic exercise. We hear in his style the attempt to maintain an authoritative literary voice that is personal and dynamic but seldom genuinely confessional. This deliberate pose can be corroborated in another work, specifically by tracing the stylistic redactions Jünger made over the course of the several editions of Storm of Steel , his World War I narrative. He drastically edited the style of that memoir by toning down or removing indications of his youthful, subjective voice. Something similar happens to the compositional process of these wartime journals. He states candidly that he does not necessarily consider the first draft of any memoir to be the most authentic and admits that he has edited, expanded, and redacted this material over time.

Читать дальше

![Эрнст Юнгер - Стеклянные пчелы [litres]](/books/410842/ernst-yunger-steklyannye-pchely-litres-thumb.webp)