Jünger was well aware of what could befall an opponent of the new regime, regardless of his war hero status. Around this time, he began burning many personal papers and letters. Because of his ties to the anarchist Erich Mühsam, the Gestapo searched Jünger’s apartment in early 1933. At the beginning of December 1933, Jünger’s family left Berlin for Goslar, in Lower Saxony on the slopes of the Harz Mountains. During the so-called Röhm Purge at the end of June 1934, in which the Schutzstaffel (SS) eradicated the leadership of the unruly Brown Shirts, as well as nearly one hundred political opponents of the regime, Jünger was vacationing on the island of Sylt but felt the threat palpably. The mood was ominous, wrote Jünger’s wife. [15] Noack, Ernst Jünger , 126.

GOODBYE TO ALL THAT

Jünger now entered a period of “inner emigration,” a term possibly coined by Thomas Mann, but one Jünger never embraced. [16] Elliot Yale Neaman, A Dubious Past: Ernst Jünger and the Politics of Literature After Nazism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 104.

He published a series of essays based on his travels, and revised The Adventurous Heart , removing large parts of the book that were political in nature. He rejected membership in the Nazified Prussian Academy of the Arts, which was “synchronized” ( gleichgeschaltet ) in the spring of 1933, forcing out many luminaries, including Thomas Mann and Alfred Döblin. The Nazis filled the writing ( Dichtung ) section with party hacks, although the Academy was headed by Gottfried Benn, a major poet who was on friendly terms with Jünger. [17] Inge Jens, Dichter zwischen rechts und links (Munich: Pieper, 1971), 33–35.

In 1934 Jünger published a collection of his essays on philosophically esoteric topics, which stood in stark contrast to the “Blu-Bo” (a contraction for Blut und Boden , blood and soil) popular literature of the period. In 1936 he published the diversionary Afrikanische Spiele (African Games), a novel about his short adventure in the French Foreign Legion.

The Jünger family moved several times in the 1930s, once down to Überlingen, on the north shore of Lake Constance, to be near his brother Friedrich Georg. But Jünger didn’t like the mild climate there, and so they finally settled in Kirchhorst near Hanover in 1939, where Gretha had found a large, somewhat run-down old house with a large garden, which would be very useful since food would soon be rationed in Germany. Jünger would live there until 1948, although he was away for much of World War II. He had another reason for moving back to Lower Saxony: unit assignments were based on residence, and he wanted to be back in his old regiment if war broke out.

Just before the outbreak of World War II, Jünger published On the Marble Cliffs , which he began writing in February 1939 on the balmy shores of Lake Constance and finished quickly in Kirchhorst at the end of July. The book was written as an allegory on the abuse of power. A peaceful seaside agricultural people are threatened by a primitive nomadic tribe from the hinterland and by the followers of an unscrupulous tyrant named the Head Ranger, whose thugs torture their enemies in a ghostly camp called Köppelsbleek. Skulls and the flayed skins of the victims surround the site. Two brothers, modeled after Jünger and his brother Friedrich Georg, are shaken from their peaceful existence and forced to flee their domicile, which the Head Ranger destroys in a violent Götterdämmerung . Jünger later denied that the novel was a cryptic assault on National Socialism, but the descriptions of the main characters in the novel are too suggestive to be pure coincidence. The Head Ranger dresses ostentatiously and throws lavish parties on his estates, just like Goering, who was in fact in charge of Germany’s forests during the Third Reich. [18] Ernst Jünger, “Auf den Marmorklippen,” Sämtliche Werke , 18 vols. (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1978–2003), 15:265.

In the war journals, Jünger repeatedly ruminates on his novel, whose readers understood it as a contemporary allegory.

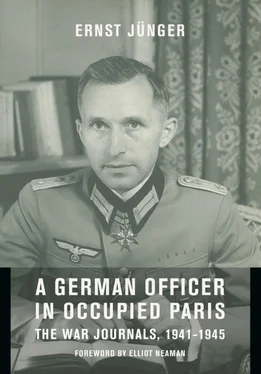

CAPTAIN IN THE CITY OF LIGHT

Jünger was conscripted as a lieutenant soon after the war broke out and reached the rank of captain. He participated in the invasion of France in the spring and summer of 1940. Then, in April 1941, his regiment was ordered to occupied Paris. Jünger was granted considerable privileges in his military posting, not the least of which was due to the fact that he did not face much physical danger apart from some English bombing raids over Paris. His office was at the Hôtel Majestic, under the command of General Otto von Stülpnagel and later his distant cousin Heinrich von Stülpnagel. He served there with Hans Speidel, a lieutenant general and later chief of staff to the famed General Erwin Rommel, as well as with Werner Best, an SS officer who was a deputy to Reinhard Heydrich, one of the main architects of the Holocaust.

Jünger had much free time to wander around the metropolis, often in civilian clothing, although he didn’t see his situation as without peril. “When I think about the difficulties of my situation compared with other people—especially those in the Majestic—I often get the feeling,” he wrote on 23 May 1942, “that you are not here for no reason; fate will untie the knots it has tied, so rise above worries and see them as patterns.” In other words, he was surrounded by opponents of the Hitler regime, who are named in the journals. With a tinge of guilt and self-reflection, he added, “thoughts like that seem almost irresponsible.” Almost but not quite irresponsible because he saw himself as part of the resistance to Hitler even though he believed that active opposition was pointless. Others around him were to pay dearly for their convictions, whereas Jünger managed to survive the war unscathed.

The lavish Hôtel Majestic is still situated on the Avenue Kléber, five minutes by foot from the Arc de Triomphe. Jünger was billeted nearby, at the luxury hotel Raphael on the Avenue des Portugais. He worked in Majestic’s Division Ic, responsible for gathering military intelligence on enemy and oppositional activities. Another of his assignments was to keep notes about the rivalry between the Nazi party and the army, which he kept, along with a diary and other writings, safely locked away in a vault at the Majestic. The diary entries formed the basis for his later published collected war journals Strahlungen ( Emanations ). The first World War II diaries, Gardens and Streets , were published in Germany in 1942 and were translated the same year into French, published by Plon, so that his fame in occupied France spread among readers in that country. The translated war diaries included in this current volume contain the two journals from his tour of duty in Paris, his sojourn in the Caucasus, and his visits and then homecoming to the house in Kirchhorst.

As a well-known author, Jünger was welcome in the best salons of the capital city. There he met with intellectuals and artists across the political spectrum. The First Paris Journal was written as the Third Reich reached the fullest extent of its continental expansion. Through reports passed on by Speidel, Jünger was privy to the brutal facts of the Russian campaign, [19] “It was horrible to hear what [General Alfred] Jodl reported about Kniébolo’s [i.e., Hitler’s] objectives” (Jünger, First Paris Journal , 8 February 1942). See also 6 April 1942 and many other entries.

and the German army was still deep inside Soviet territory until well after the end of the Battle of Stalingrad in February 1943. Not surprisingly, some conservative Parisian intellectuals greeted the Pax Germanica with cheers, hailing the demise of the disorganized and highly fractured French Third Republic. The sympathizers of the New Order included the dramatist Sasha Guitry and the writers Robert Brasillach, Marcel Jouhandeau, Henry de Montherlant, Paul Morand, Jean Cocteau, Drieu la Rochelle, and Paul Léutaud. To call these intellectuals antirepublican “collaborators,” however, depends on the word’s definition and on whether or not they played any official role in cooperating with the German authorities. The word “collaborator” is thrown around too loosely, even by historians today. But that a Franco-German intellectual alliance between 1940 and 1944 was forged, can hardly be doubted. That the Germans often understood that relationship differently from their French counterparts must also be considered when reading these journals.

Читать дальше

![Эрнст Юнгер - Стеклянные пчелы [litres]](/books/410842/ernst-yunger-steklyannye-pchely-litres-thumb.webp)