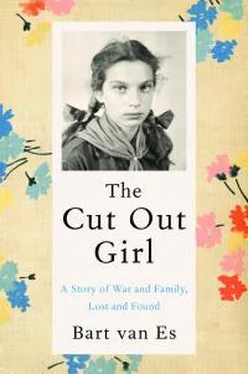

Darkness has fallen by the time that Lien mentions her poesie album: a kind of poetry scrapbook that nearly all girls in the Netherlands used to keep. At first she cannot find it, but then, after looking around in a side room, she suggests I stand on a chair and look on top of the bookshelf, where it lies wedged, kept safe from dust in a small, transparent plastic bag. It is a gray cloth album of around three by four inches with a faded pattern of flowers on the cover. Inside on the first of its facing pages there is a set of rhymes that are signed “your father” and dated “The Hague, 15 September, 1940.”

They begin as follows:

This is a little book where friends can write

Who wish for you a future bright

To keep you safe throughout the years

With many smiles and never tears.

I stand for a moment reading the sloping hand. Opposite, on the left, there are three old-fashioned paper cut outs in pastel colors: at the top, a wicker basket of flowers; and below, two girls in straw hats. The one on the right smiles and looks happy, like Lien’s mother in the photo, but the cut out girl on the left purses her lips as she clutches her posy. She glances sideways, as if unable to meet the viewer’s eyes.

One

It is really Hitler who makes Lien Jewish. Her parents are members of a Jewish sports club (there is a team photo that shows her father dressed in thick socks and an open-necked shirt), but other than that, they are not observant.

They eat matzo at Passover and, under family influence, got married at a synagogue. Lien, aged seven, however, thinks more about the Dutch equivalent of Father Christmas, St. Nicholas, and still remembers her fury at being told that he does not really exist. She feels a trick has been played upon her by the adults and hides herself in rage and embarrassment in the cupboard beneath the stairs that lead to the apartment above.

That cupboard at 31 Pletterijstraat, The Hague, is just across the hall from her bedroom, which faces you as you come in through the front door. As you enter her room there is a line of four little windows right up against the ceiling, too high to look out of, that give a rather dim light. These windows connect to the back bedroom, where her parents sleep. The other bedroom, which looks out onto the road and connects to the kitchen, is sublet by Mrs. Andriessen. She is elderly and rather a great lady, and, like everyone else, writes in Lien’s poesie album. “Dear little Lien, remain obedient and good, / and all shall love you, as they should,” she instructs the child. Lien pays more attention to the flower pictures that are stuck in by Mrs. Andriessen than she does to this wise advice.

By April 20, 1941, when Mrs. Andriessen writes her entry, it is not easy for Jews to be obedient in occupied Holland. Jews must carry identity papers stamped with a J ; they are banned from the civil service, from cinemas, cafés, and universities; Jewish ownership of a radio is a criminal offense. But for Lien things are still just about normal. She goes to a mixed school and the children’s names written in her album with careful fountain pens are, for the most part, not Jewish:

“Let’s remain friends forever, dear Lientje, what do you think of that?” writes Ria.

“A sunny, happy life, may it remain yours forever” from “your girlfriend, Mary van Stelsen.”

“Will you still remember me, even without this album page?” asks Harrie Klerks.

This last entry causes Lien some upset because, in spite of promising to work tidily, Harrie blots and spoils a page of the album so that it needs to be cut out with a paper knife. Still, Lien generously gives him a second try.

Lien’s real worries, if she could formulate them, are not about the war but about her parents’ marriage. When she was very young, just two and a half, she had to leave the flat above a shop that they then rented to go to live with Aunt Fie and Uncle Jo and their two children in another part of town. Her parents got divorced. Mamma came to visit her, but she did not see Pappa for a very long time. After two years Mamma and Pappa got remarried and set up home in the Pletterijstraat, turning over a new leaf.

Pappa has stopped traveling as much as he did when he worked as a salesman for Grandpa and he makes an effort to stay home at night, making children’s puzzles out of wood at the table under the big light in the kitchen. For Lien he makes a little painting of Jan Klaassen and Katrijn, the Dutch Punch and Judy, which is her most treasured possession. Jan Klaassen and Katrijn are sitting in the sunshine on top of a gray cloud that is raining down beneath them, holding umbrellas in their hands as they smile. Perhaps Jan Klaassen and Katrijn are a bit like Mamma and Pappa, who are happy now that they are out of the rain?

Lien gets terrible stomachaches and does not like eating anything except desserts. She has medicines from the doctor, and one time when she got really thin she had to go and stay for six weeks in an infirmary, where you have to drink a lot of milk and eat porridge. It would be horrible to go back there, so she tries to eat as much as she can of the farmer’s kale-and-potato mash that Mamma makes her, but it always takes a very long time.

For his new job Pappa has a little factory like Grandpa’s, which is really no more than a shed and can be reached through the yard at the back of the flat. He makes jams and pickles using vats of fruits and vegetables and various sizes of glass jars. Lien watches while Pappa works, but she is not allowed to help because this is a very clean job that children’s fingers might spoil. Instead, she is mainly to be found on the street singing nursery rhymes and playing games like “Where shall I lay my handkerchief?” with children huddled in a circle and one child going round and round until she finds someone to give the handkerchief to, who must then chase her to try to give it back. Lien loves this kind of playing; she is almost always outside when there is sunshine and will even put up with a bit of rain if there is fun to be had.

She also goes to ballet, which is very ladylike, and sometimes they have shows. In Mamma and Pappa’s bedroom there is a picture of her in front of the stage scenery.

It was taken after a performance: she is wearing her costume of black skirt and white blouse and she holds up a glove puppet on her right arm. The puppet is rather lumpy and bumpy and looks owlish, but it is supposed to be Mickey Mouse. Apart from the ballet costume, she loves her two best dresses. One is blue-gray silk, which she bought with Mamma on a shopping trip to the Bonneterie, the enormous department store with glass doors and a high ceiling that swallowed them up when they stepped inside. Its floors are so shiny you can see your face in them, and when you look down from the inside balcony onto the entrance hall the people below you look like ants. The other favorite is a little bell-shaped dress (known as a clock dress) of satin, with petticoats underneath that her mother made by hand.

Lien’s world is a world of school, street games, and of grannies and grandpas, aunts and uncles and cousins. There is family all around them: at the end of short walks from the Pletterijstraat or at the end of short rides on the tram. In the summer they take the tram to Scheveningen, where they play on the beach. Pretty, the family dog, loves it there—running as fast as she can on the wet sand, just touching the water, leaving a long line of four-toed impressions for the sea to wash away. When Lien throws a tennis ball for Pretty she gets it back, moments later, all soggy and sticky and covered in sand.

Her favorite cousins are Rini and Daafje. They are almost like a brother and sister because Lien stayed with them for such a long time when Mamma and Pappa could not be friends. On one of the many days they spend together, Rini writes a short moral verse in the poesie album about “taking people as they come.”

Читать дальше