James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

An initial plan drawn up by a New York architect seemed wrong at first sight. He would have given Airslie a formal Federal style appropriate for rich New England merchants. Somehow we had to find an imaginative designer to give the place its own character. Luckily I had just read that the celebrated Yale architect Charles Moore was doing a low-cost housing project in nearby Huntington Station. The year before, staying in the “honeymoon suite” of Sea Ranch, the resort he created above San Francisco, Liz and I had much admired the daring of its multiple sloping roofs. I arranged for Moore's next visit to Long Island to include a brief visit with us. A week later, Liz and I were observing up close his playful mind reimagining Airslie.

Luckily Moore's plan was within the Lab's fiscal reach. Less than a month passed before we saw his final scheme while he was up at Harvard lecturing to architecture students. We were immediately taken with the way he opened up the front of the house into a three-story

hall, giving Airslie for the first time a large central staircase. On our next visit down to Cold Spring Harbor I shared the plan with the trustees, a little apprehensive imagining what they might make of the bold way Moore created large, open spaces from tight, smaller rooms. In particular, I worried what our new chairman and nearby neighbor, Bob Olney, would think. Happily, Bob approved, provided the local preservation society didn't object. On their subsequent visit, the society's president declared that Airslie lacked any design features worth preserving. His only concern was with saving some ancient panes of glass. Though it was rather impractical, we resolved to keep the small 150-year-old glass pieces that ran along both sides of the front door. And so early in the fall of 1973, when Airslie was no longer needed for overflow summer housing, the fourteen-month project started. The final cost of just under $200,000 seemed embarrassingly extravagant for housing the director. Once we moved in, we realized that Moore's unique design gave Liz and me a way of life usually enjoyed only by the very wealthy. But it occurred to me that one day this would help us lure my successor; contrary to stereotype, most scientists are far from indifferent to the finer things in life.The following year, Robertson Research Fund money let us readapt Jones Laboratory into a year-round neurobiology facility. Charles Moore and his highly talented young coworker Bill Grover imaginatively placed the four specialized neurobiology modules as freestanding aluminum-covered boxes accented by boldly colored wooden strips. Charles Robertson and his new wife, Jane, came to its dedication ceremonies. Earlier in the summer, the Robertsons had invited all the speakers at the June symposium on the synapse for a late afternoon party. It marked our gracious host's last year in the home he had so lovingly occupied for almost forty years. By then he had given up plans to build a modest summer home next door to our proposed conference center, accepting that his and Jane's future would be mainly spent in Florida at his large waterfront estate in Delray Beach.

Even before Airslie was gutted and the electricity turned off, Liz and I wondered whether it soon might be our year-round home. How long Harvard would continue to let me be away so much was not yet settied.

Living in two places, moreover, would become less practical once Rufus reached kindergarten age. Early in 1973-74 I informed Harvard that I might move out of Kirkland Place when my spring term responsibilities ended. Many of its furnishings would go to Airslie and others to the house we had just bought on Martha's Vineyard.I had wanted a summer home on the Seven Gates Farm on Martha's Vineyard since becoming aware more than a decade before of its thousand-acre vastness, on which corn was still grown. I knew several of the farm's civilized summer denizens very well, including our Cold Spring Harbor neighbor Amyas Ames, former chairman of Lincoln Center, who had presided over LIBA in the last year of Milislav Demerec's directorship. Owning one of its only thirty houses, however, seemed beyond my means until late August, when a Vineyard Haven real estate agent took us to a simple early-nineteenth-century farmhouse just put up for sale by a man about to retire to low-tax New Hampshire. Were we to sell the house on Brown Street in Cambridge, bought using my Nobel Prize monies, we could just cover the purchase price. The idea became irresistible once we imagined ourselves basking in the shade of the two magnificent American elms overhanging the wide farmhouse lawn. Equally important, only five miles away was Ed and Lucy Pulling's West Chop beachfront summerhouse.

From 1971 to 1973, my main teaching responsibility was a yearlong introductory undergraduate course on biochemistry and molecular biology (Biochemistry 10). In preparing for a spring 1972 lecture on DNA replication, I saw the need to point out the commonly accepted 5'→3’ DNA chain elongation mechanism led to incomplete double helices with single-stranded tails. Some molecular mechanism had to prevent DNA molecules growing ever shorter during each round of replication. Until then, no one understood why identical, redundant DNA sequences were found at the two ends of all linear phage DNA molecules. Suddenly I knew why. Redundant ends allowed right and left single-stranded DNA tails to hydrogen-bond to each other to form dimers. Further cycles of DNA replication would lead to ever longer phage DNA molecules. No longer mysterious to me was why replicating phage DNA molecules are many times the length of infecting

phage DNA molecules. Excited by my brainstorm, I told it to my Biochem 10 students and, afterward, wrote it up for an article in an October 1972 issue of Nature.

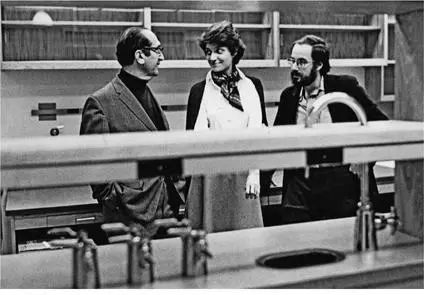

Salvador Luria, Nancy Hopkins, and David Baltimore at the MIT Cancer Center in 1973

Soon my main concern at Harvard turned to making the Biological Laboratories another major site for tumor virus research; after coming strong into the molecular age, Harvard was risking again being behind the curve. In April 1973, however, the National Cancer Institute turned down Harvard's application for construction monies for animal cell facilities. The proposal's reviewers were not convinced that the building addition would be used in a way that well served NCI's mission. True enough, given my Cold Spring Harbor responsibilities, I would likely never directly oversee a tumor virus lab in Cambridge. Nor was it clear whether Mark Ptashne would abandon gene regulation in bacteria to work on retroviruses. And Klaus Weber might go back to Germany were he offered a high-level appointment. In contrast, MIT's application for NCI construction funds was approved without a hitch.

Actually, it was a shoo-in with David Baltimore and Salvador Luria as its main drivers. Soon they would conscript two Cold Spring Harbor initiates into tumor virus research: Nancy Hopkins, after two years in Bob Pollock's lab, and Phil Sharp, after three highly productive years in James Lab.Moving much too slowly were the joint efforts of the Biology Department and BMB to recruit a tenure-level RNA retrovirologist. Though discussions began in the fall of 1972, letters seeking advice from eleven referees did not go out until six months later, in February. The referees were asked to compare as candidates Mike Bishop, Peter Duesberg, Howard Temin, Peter Vogt, and Robin Weiss. Temin's name was high on most lists, although with the caveat that he was not a consistently good lecturer. Two respondents advised that we also consider Harold Varmus. Mike Bishop was not on top of any list except for Bob Huebner's, who called him a highly intelligent biochemist as well as a lucid teacher.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.