James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

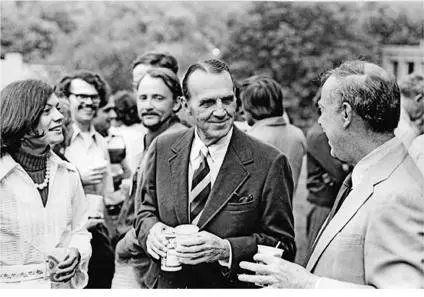

With Edward Pulling at the annual meeting of the Long Island Biological Association, December 1976

Joining Charlie on his visit was his long-valued New York legal counsel, Eugene Goodwillie. After Marie's sudden death, Goodwillie told Charlie to quickly establish a legal residence in Florida. In this way, his estate would not be socked with punitive New York inheritance taxes. By the same logic, it was best for Charlie not to hang on to the Long Island estate, to which he felt such deep sentimental attachment. Its land had once belonged to his mother's Sammis family, and his marrying into great wealth allowed him to reclaim it. To keep the land forever intact, rather than subdivided into two-acre building plots, Charlie resolved to give it to a nonprofit institution. To be settled today was whether Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory was the worthiest beneficiary of the Banbury Lane property.

Charlie Robertson with me and Liz at CSH, September 1974

The visit started off well, with Charlie sensing the frenetic pace of the James Lab tumor virus effort as well as the boldness of the picture-window offices and seminar room of the James Annex. My grand office alone spoke of how the Lab was again on an upward course. Before lunch, I walked the sixty-seven-year-old Charlie and even older Eugene Goodwillie up to the Page Motel to introduce them to our living history in the persons of Max and Manny Delbrück. Delbrück had just arrived from Pasadena for a three-week Phycomyces workshop. Then, rather imprudently, I led my not-so-nimble guests down the steep one-hundred-foot path to Bungtown Road. Neither visitor stumbled, though they were only half smiling when we safely reached Osterhout Cottage. There they joined Ed Pulling for a lunch that Liz had taken great pains to prepare. She ate virtually nothing as she jumped up and down serving several courses that started with consommé Bellevue topped with horseradish-flavored whipped cream.

After lunch, Goodwillie drove back to New York City while I followed Charlie to the sixty-acre estate that sloped down to the eastern shore of Cold Spring Harbor. Before the war, much of it was still farmland,

but that afternoon only several empty chicken coops spoke of that history. For the past thirty-five years the main house had been a large whitewashed brick Georgian structure built in 1936, and in it Charlie and Marie had raised their five children. Below the house, halfway down the sloping bluff, was a large saltwater swimming pond, which the children when young used to enter raucously, I was told, via a long steel slide. But the children were now grown and, furthermore, recipients of generous trusts, leaving Charlie free to dispose of his estate without detriment to them.I sensed Charlie wanted us to do real science on his lands, and so to be straight with him I had to confess, nervously, that dividing our research facilities into two sites was not realistic. Instead I saw the best use of his land and buildings as a high-powered conference center similar to that of the CIBA Foundation on Portland Place in central London. Toward that end, the high-ceilinged, seven-bay garage could easily be transformed into a perfect meeting room for thirty to forty people. That night, Liz and I went to sleep not at all sure that the gift of the Robertson estate was what we now needed. Spending time to raise monies for conferences on Banbury Lane would divert us from raising funds to expand our cancer research programs.

To our relief, Charlie took less than a day to reach a decision that far exceeded our most optimistic hopes. Late the next morning, we learned that he had decided it made no sense to give his estate to an institution surviving hand to mouth. He would soon have Eugene Goodwillie draw up documents establishing an $8 million endowment to support research on the lab grounds. In return, we would accept the gift of his estate, which he would separately endow with $1.5 million. It should generate funds covering the annual operating costs of his estate, including a large annuity to be paid to Lloyd Harbor in lieu of taxes. The estate would come with a covenant to the Nature Conservancy, preventing any changes to the building and lands except for the building of a new residence to complement the visitors’ rooms in the main house.

The remainder of the day we walked about in a virtual daze, half worrying that becoming rich would destroy the Lab's unique way of doing science. But we soon returned to our senses and accepted the

generous offer. Even with the forthcoming Robertson monies, we had more expenses than funds to cover them. Many key Lab buildings remained habitable only during the summer, and fixing them up for year-round use could easily occupy the rest of the decade.

Robertson House in the 1970s

Over the past six months, we had used accumulated profits from symposium book sales to winterize and totally renovate Cold Spring Harbor's original Firehouse. After buying it in 1930 for $50, the Lab had rented a barge to bring the building across the inner harbor to a site next to Davenport Lab, where it was subdivided into three apartments for summer use. Handling the badly needed renovation in 1972 was a local builder, Jack Richards, who had joined the Lab staff the year before to oversee construction of the James Lab Annex. Large picture windows, to rival those of Osterhout and the James Annex, were installed, creating views on the inner harbor from each of the three apartments, converting them from utilitarian to spectacular. Richard Roberts, the English chemist soon to move from Harvard, bringing the Lab expertise in nucleic acid chemistry, would occupy the

topfloor apartment with his wife and two children. Below him would be Ulf Pettersson and his family, leaving behind a cramped apartment in a barn on Ridge Road. The basement flat would house Klaus Weber and his wife, Mary Osborn, soon to come down from Harvard to learn how to work on proteins of animal cells grown in culture.Klaus Weber had risen rapidly at Harvard since joining me as a postdoc in the spring of 1965 to do protein chemistry on RNA phages. Recently promoted to full professor, he did not yet have the research facilities that normally go with the rank. All his previous research triumphs had come from using microbial systems, but he foresaw a bigger future for himself in moving on to animal cells and their related viruses. To learn how to grow and use them, he had just been granted a sabbatical leave for a year's work at Cold Spring Harbor. Going back to Harvard afterward would make sense only if they could provide space specifically outfitted for work with animal viruses. Toward that purpose, in the spring of 1972,1 helped prepare a big application to the National Cancer Institute for funds to construct an extension to the Harvard Biological Laboratories. Mark Ptashne would potentially join Klaus in the new space. He too was keen to work on cancer-causing retroviruses since taking the tumor virus workshop the previous summer (1971). The idea was spreading: MIT was thinking of proposing to use “war on cancer” funds to create a similar facility by converting a former candy factory virtually adjacent to its main campus.

Next on the facilities agenda of Cold Spring Harbor was the winterization of Blackford Hall, courtesy of LIBA's amazingly fast $250,000 fund drive. Unfortunately, Jack Richards found it painful to work with Harold Buttrick, the well-connected New York architect that a LIBA supporter had chosen for the project. A direct descendant of Stanford White, Buttrick thought himself of higher caste than the builders there to take orders. After the project ended, I quietly made Ed Pulling aware that Buttrick and Jack had irreconcilable differences.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.