James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

3. Races within the same building bring on heartburn

A serious competitor aiming for the same objective inherently creates anxiety. It is emotionally draining to wish ill upon anyone constantly nearby, yet few, if any, human psyches are capable of turning off the visceral wish for an opponent to stumble. In science, the journey is not the destination; the destination is the destination. And so it is better that one's competitors be in a different city, if not country. Having them in the same building is a small model of hell, and not even an efficient one. Once Jacques Monod had two research teams working in adjacent labs attempt to make ß-galactosidase in the test tube. Maybe he knew their respective leaders already disliked each other. Anyway, in that spring 1962 race, no one crossed the finish line.

4. Close competitors should publish simultaneously

Science works better when the winners do not take all. The agony of losing a very close race may break the spirit of a competitor who may again bring out the best in you. And so when you beat someone across the line by only a nose, offer to publish at the same time, if not back to back, in the same journal. Those scorekeepers in the know usually are aware what happened and will think more highly of you. Doing unto others may also yield reciprocal benefits the next time you are oh-so-close.

5. Share valuable research tools

Do not hog powerful new research tools or reagents. If Dick Burgess had not shared his GG and PC RNA polymerase preps with his lab neighbor Jeff Roberts, he unlikely would have been the first to discover σ factor. One hand washes the other. Though it was sharing his RNA polymerase protocols with Ekke Bautz and John Dunn that brought them into his game, they later immediately shared their discovery that σ factor disappears following phage T4 infection. This openness further helped Andrew Travers get an early start in the hunt for phage-specific σ factors.

14. MANNERS FOR HOLDING DOWN TWO JOBS

IN THE FALL of 1967, Harvard gave me permission to become the director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory while remaining a full-time member of the faculty. They did so upon realizing that Cold Spring Harbor's precious research and educational resources were on the brink of disaster and would likely disappear unless someone stepped in to make this unique Long Island institution financially viable. I was already a member of its board of trustees and knew its shaky state through my close friendship with its sharp-minded director, John Cairns. Born and bred in North Oxford, John exuded an ironic intelligence as well as an inability to seek help from individuals who had more power than warranted by the agility of their brains.

Since arriving from Australia in July 1963, John increasingly had come to see the biochemist Ed Tatum, chairman of his Board of Trustees, as a personal nemesis. On paper he seemed an asset. Tatum, then a professor at Rockefeller, had done research at Stanford in the 1940s on gene-protein relationships that led to his sharing the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with the Nebraska-born geneticist George Beadle. But Tatum was a polite plodder who would have gone nowhere but for Beadle, and later at Yale he was propped up by his graduate student and protege Joshua Lederberg. The sharp intellectual crossfire of the geneticists and molecular biologists who spent summers at Cold Spring Harbor was not Tatum's cup of tea. Prior to his becoming chairman, he had attended only one summer symposium. Much to John Cairns's annoyance, Tatum arranged for all

trustee gatherings to be held in New York City at Rockefeller University. Avoiding the thirty-mile trip east, the chairman spared himself and the other trustees having to see the decrepit state of the some twenty-five buildings on the Lab's almost one-hundred-acre campus. At board meetings, Tatum's demeanor reminded me ofthat of Nathan Pusey Neither knew how to handle individuals who presented unwanted facts.

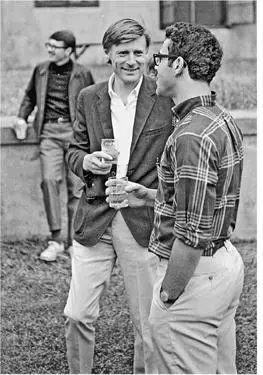

John Cairns (center) at the 1968 symposium

By the time I joined the board, John operated in day-to-day uncertainty, even though he had converted the lab's $50,000 negative cash balance to a surplus of some $100,000. Three years of hard physical and mental effort had been required, including his oft cutting the Lab's many green lawns himself. At the same time, the Lab's endowment remained effectively zero, and its survival depended upon the success of its small number of scientists each obtaining one to several

significant research grants, which supported not only their science but also the budget for administration, facilities maintenance, and the like. Apart from this grant income, the only other major barriers to insolvency were a few corporate sponsorships and the ever-increasing sales of the lab's annual symposium report, a must-have volume for anyone in molecular biology.By mid-1966, John began to talk about quitting, and such talk only increased as Tatum showed himself entirely unperturbed by it. But several key junior scientists took note and in turn began to seek jobs elsewhere. In early 1967, John submitted his resignation, effective upon the selection of a successor. By then it was cold comfort to John that Ed Tatum would be gone even sooner. Replacing him as chairman was an H. J. Muller-trained geneticist from Texas, Bentley Glass, whose association with the lab went back to the late 1930s. Recently he had moved from Johns Hopkins to become provost of the new Long Island campus of the State University of New York, at Stony Brook.

Bentley knew that he alone could not dramatically improve the Lab's chances for survival. Though he was connected to innumerable government funding sources, no new monies would flow to Cold Spring Harbor until an appropriate new director was found. When I flew to New York City for the Lab's late October trustee meeting, I feared they might choose the German phage geneticist Carsten Bresch, then looking for an escape from an insecure job in Dallas. If Bresch were to come, he would continue the Lab's historically strong focus on molecular genetics. But I feared that he would see the job as a way station for him until a permanent, well-financed position was created in Germany.

Still, this was not an objection likely to sway my fellow trustees. Better a temporary leader than none, the others would counter. So I threw my hat into the ring, saying I would accept the directorship if I could simultaneously remain at Harvard as a full-time member of the faculty. In this way, the Lab trustees would be spared the need to find a source from which to pay the new director. Since his arrival, a five-year grant from the Rockefeller Foundation had covered John Cairns's $15,000 annual salary. But one could not count on an extension of this

grant. As soon as I raised the possibility of my leading Cold Spring Harbor, further discussion about Bresch subsided. I sensed that if Harvard said yes, the job was mine.Before coming down to New York, I had not consulted with anyone about the likelihood of Harvard's allowing me to hold two academic positions simultaneously. So immediately upon returning to Cambridge, I contacted Paul Doty, who had assumed his role as first chairman of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. After receiving positive concurrence from its members, he wrote to Franklin Ford on November 22 proposing that I serve as director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory for a five-year interval. During this time, I would continue my current Harvard teaching and committee responsibilities while being in Cold Spring Harbor for three days every two weeks on average. Only five days passed before Ford wrote with his approval, noting that he would have to pass my request on to the Harvard Corporation for official endorsement. I so wrote Bentley, who in turn asked other board members for a formal endorsement of my selection as director. On February 1,1968, my new responsibilities began.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.