James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jeff's unexpected negative result made Dick wonder whether his PC purification procedure had removed an RNA polymerase component necessary for transcription of phage DNA. To test this possibility, he passed a fresh batch of GG enzyme over a PC column to see whether this again led to a loss of phage DNA's transcription ability. After getting the same negative result as Jeff, he showed that the PC enzyme could be activated by adding back a protein that had been extracted in purification. Experiments done the following week by our English postdoc Andrew Travers demonstrated that a single polypeptide chain, soon to be called σ factor, was the GG-enzyme-containing ingredient lacking in PC preps.

Less than a week passed before Dick heard that Ekke Bautz at Rutgers and his student John Dunn had obtained the same results using GG and PC enzymes following the protocol he had sent them in July. At my suggestion, Dick immediately contacted Bautz to see whether they would like their work included in a joint lab paper on the σ factor

to be submitted to Nature. Liking the idea, they came up to Harvard on November 6. For me their presence was also a distraction from the unbearable cliffhanger of the presidential elections that day. Richard Nixon's victory over Hubert Humphrey would become clear only late that night. Even the discovery of σ factor did not alleviate the gloom I felt the rest of the week at the prospect of a Nixon presidency.

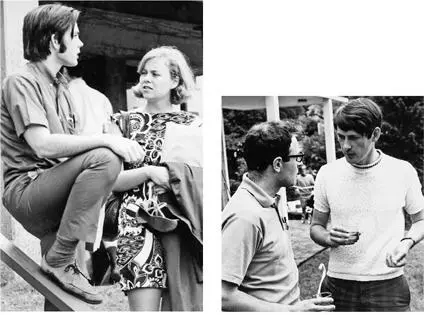

At the 1970 Cold Spring Harbor symposium: Jeff Roberts with Ann Burgess (left) and John Richardson with Dick Burgess (right)

On Monday morning, November 11, a silver lining briefly presented itself. In that day's Crimson I read the supersize headline “Pusey to Quit Harvard.” The accompanying article reported that Presidentelect Nixon had paid an unannounced visit to Harvard, coming secretively at 9:00 P.M. the night before, to ask Pusey to become his Postmaster General. After a frank and comradely conversation, during which tea and vanilla wafers were served, Pusey accepted later declared to be “the greatest moment of my life.” All too soon, however, the happy glow permeating my being dissipated. Lower on the page was

another story reporting that the proposed JFK Library was to be moved from Cambridge to Bayonne, New Jersey, making me realize I was reading one of the hoax issues Crimson editors occasionally created, perhaps to assure themselves that no want of wit had consigned them to the Crimson rather than the Lampoon. After this monumental letdown nothing in the Crimson ever seemed funny.When the manuscript announcing σ factor was submitted to Nature on December 2, it contained only data obtained at Harvard. The equivalent experiments from Rutgers had been done fewer times and were less complete. “Factor Stimulating Transcription by RNA Polymerase,” by Burgess, Travers, Dunn, and Bautz, speedily appeared as a full article in January 1969. Before publication, I announced our lab's breakthrough in a lecture to Arthur Kornberg's perennially self-congratulatory Biochemistry Department at Stanford. It was a moment I never dreamed would come: our Harvard Biolabs demonstrating the biochemical competence to take on and best mighty Stanford.

In mid-December, Dick and Andrew had heard from Ekke Bautz and John Dunn that σ molecules disappear from cells infected with T4 phage, explaining why host bacterial RNA synthesis stops soon after phage infection. Phage DNA molecules likely coded for phage-specific σ factors that directed core RNA polymerase molecules to specific signals on their respective DNA. Over the next six months, Andrew Travers confirmed this conjecture and sent a paper to Nature in August called “Bacteriophage Sigma Factors for RNA Polymerase.” In its conclusion, he speculated that σ-like transcription factors might be responsible for the massive shifts in RNA transcription patterns underlying the development of higher organisms. Sensing again a major paper on their hands, Nature editors rushed it into print in just over a month.

By early February, Dick had defended his thesis and started a Helen Hay Whitney postdoctoral fellowship that would let him remain at Harvard until his intelligent, blond wife, Ann, finished her Ph.D. thesis. She hailed from a prosperous, hardworking Wisconsin family and did her experiments on bacteriophage ΦX174 down the hall in Dave

Denhardt's lab. By then, Dick knew that not one but two ß chains existed in the core (PC) RNA polymerase particle whose structure was α2ββ He and Andrew, furthermore, had preliminary evidence pointing to how σ functioned in the initiation of RNA synthesis. Its role was to direct the core α2ββ1 complex to appropriate starting sites to the DNA for RNA synthesis. RNA polymerase's enzymatic property is solely owing to its α2;ββ1 core component.The relative importance in controlling gene regulation of repressore and operators versus σ factor shifts still remained open. Bernie Davis at Harvard Medical School bet me a case of wine that my group would not discover a second bacterial σ factor over the next two years. Andrew then had let Bernie know of his tentative evidence for a σ factor controlling ribosomal RNA synthesis. Here time was not on his side, costing me a case of cabernet. But Richard Losick, a newly appointed junior fellow, had begun experiments in the Biolabs on how Bacillus subtilis forms spores, soon getting hints of a possible σ factor specific to bacterial sporulation.

The first visible recognition of σ factor's importance came in November 1969 at a meeting in Florence, Italy, on RNA polymerase and transcription. Dick Burgess gave the opening talk, coming from Geneva, where he was now a postdoc in Alfred Tissières's lab. Sponsoring the meeting was Lepetit, the Milan drug company whose rifamycin and rifampicin antibiotics had been shown to inhibit bacteria through binding to the ß subunit of RNA polymerase. At this meeting, Jeff Roberts announced his recent discovery of a protein called p that halts RNA synthesis at specific stop signals on DNA molecules. Just before coming to Italy, he sent off his manuscript “Termination Factors for RNA Polymerase” to Nature, which published it in December 1969.

Though the low sun was not optimal for picture viewing in the Uffizi Gallery, the Palazzo Vecchio provided a reception site equal in its satisfactions to the science of the three-day gathering. Even being forced to listen to a minister up from Rome could not diminish the pleasure of knowing that the Biolabs were still at the center of how genes are regulated.

Remembered Lessons

1. Two obsessions are one too many

Experiments, like many speculative enterprises, are likely to require at least five times more effort than you initially guess. Being a really good anything—be it university president, violinist, securities lawyer, or a scientist—requires a virtually obsessive devotion to one's objectives. Dividing one's attention will give the edge to competitors who have the same talent but greater focus. For this reason, highly successful bankers who also claim to be accomplished cellists are often neither. Their banking reputation likely rests on the labors of talented associates working day and night, and their cello playing as likely suffers from the time lost to even the pretense of being a banker.

2. Don't take up golf

The moment golf clubs are first spotted in your trunk, you will be subject to constant ribbing. Only the rare few content to play occasionally with no fantasy of breaking 90 should even consider hitting the links. Once you become obsessive about bettering your personal best—say, now 94—your weekend science experiments cease. You have become a thank-God-it's-Friday scientist, always fighting not to fall too embarrassingly behind those peers who have sensibly chosen the less Zen but more aerobic thrill of hitting tennis balls.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.