James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I was pleased to be told that among former 10 Appian Way tenants were the writers Owen Wister and Sean O'Faolain. The building's ancient central heating system was less charming. In winter I routinely needed an electric blanket to sleep. My flat's Spartan features were made for inexpensive furniture I bought from the Door Store on Massachusetts Avenue on the way to Central Square. Soon to complement its simplicity was a big-planked New Hampshire harvest table

that I found in an antiques store near Falmouth on Cape Cod. I hoped its inherent elegance would inspire some Radcliffe girls to test their cooking talents in my tiny kitchen.By early fall I had lost all hope that the astute geneticist Guido Pon-tecorvo would move from Glasgow to fill the senior geneticist's slot turned down by Seymour Benzer. Six months before, the ad hoc committee called to look over Benzer had also judged Ponte's accomplishments worthy of a major offer, a conclusion simultaneously reached by the electors of the soon-to-open chair of genetics at Cambridge. But Ponte had strong attachments to Glasgow, where his colleagues had solidly stood by him during the difficulties that followed his physicist brother Bruno's sudden flight to Moscow just before he was to be charged with treason for passing atomic bomb secrets to Soviet agents. Ponte, in turn, stood by his friends by refusing to go to either Cambridge.

That fall, knowing that I would be teaching undergraduates in the spring, I gave a graduate-level course on the biochemistry of cancer. During my previous winter weeks at the University of Illinois, I learned that uncontrolled cell growth should be the province of the biologist as well as the medic. There the biochemist Van Potter, from the University of Wisconsin, gave an evening colloquium on cancer, making me aware that at any given time most adult animal cells are not undergoing cell division. To duplicate their chromosomes and divide, these cells must receive molecular signals that initiate chains of events culminating in the production of enzymes involved in DNA synthesis. In contrast, cancer cells very likely do not require external signals to enter into cycles of growth and replication. Future searches for such intrinsic mitosis-inducing signals would quite likely involve the already long-known tumor viruses. Upon infecting so-called non-permissive normal cells, they do not initiate rounds of viral multiplication but rather transform the healthy cells into their cancerous equivalents. The Shope papilloma virus, already known for more than two decades to induce warts on rabbit skin, particularly intrigued me. Only a few genes were likely to be found along its tiny DNA molecules, made up of a mere five thousand or so base pairs.

Over the past summer at the Marine Biological Laboratory in

Woods Hole, I had met the biochemist Seymour Cohen, then very upbeat about his lab's recent discovery that T2 phage DNA contains genes that code for enzymes involved in DNA synthesis. Initially I did not attach the proper importance to Cohen's finding, but I abruptly changed my mind several months later when preparing a lecture on Shope papilloma tumor virus. Then I found myself asking whether its chromosomes, like those of T2, also code for one or more proteins that trigger DNA synthesis. Since at any given moment the vast majority of adult cells do not contain the large complement of enzymes necessary to make DNA, conceivably all DNA animal viruses had genes whose function was to activate synthesis of these enzymes. Even more important, these genes, if somehow integrated into cellular chromosomes, might make the respective cells cancerous. I was in a virtually manic state as I presented these thoughts to my class. At last I understood the essence of a tumor virus. Over the following days, however, I realized that my excitement did not infect those about me. Only those who come up with the seductively simple ideas initially get hysterical about them. Everyone else demands experimental proof before joining the conga line.I was still high on my theory by the time of a Sunday cocktail party given early in 1959 by David Samuels, the British-Israeli chemist who had recently arrived at Harvard as a senior postdoc under the bio-organic chemist Frank Westheimer. David was in line to be a British lord, like his father and his grandfather, the first Viscount Samuels, an influential early backer of a Jewish state in the holy land. Now he was still saddened over the death of his cousin Rosalind Franklin from ovarian cancer the past April. They had seen each other often during their school years. But after he chose Oxford and she Cambridge for their education as chemists, their paths less often crossed. It was only now that I realized that Rosalind had come from no modest background. Had she wished, she easily could have moved into the world of moneyed society that David now so obviously enjoyed when not applying himself as a serious chemist.

The most striking of David's guests that afternoon was the Radcliffe senior Diana de Vegh. Quickly making a move to her side, I learned that her investment banker father, Imre de Vegh, was a Hungarian,

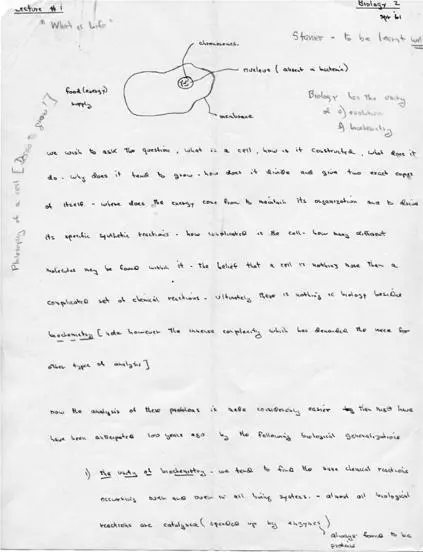

while her mother was a Social Register Jay. As such, she had sampled both Brearley and Miss Porter's School before being admitted to Rad-cliffe, where she had effectively managed to avoid any science. Now she lived in one of the off-campus houses favored by her fellow private school friends. Her comings and goings were much less conspicuous than would have been those of an inhabitant of one of the large red brick dorms surrounding the Radcliffe Quad up Garden Street. David, in observing Diana give me her telephone number as she went off to another party, took immediate pleasure in telling me that she had earlier attracted the attention of Senator John Kennedy. His official car recently had been sent from Boston to fetch her upon one of his recent returns to check in on his Massachusetts constituents.Soon I was to phone Diana to ask her to lunch after one of my Biology 2 lectures. This new course, a one-term offering, was intended for students already possessing some background in biology. They would have benefited most from a coherent series of lectures given by one person, in the manner of the long-successful Chemistry 2 taught by Leonard Nash. But my department had opted for Biology 2 to have four instructors, thereby ensuring a virtual potpourri of facts and ideas for its students to master. But with me as one of its four instructors, DNA was bound to be much talked about.

The theme running through all my talks was the need to understand biological phenomena as expressions of the information carried within DNA molecules. Many, and I hoped most, students must have been desperate after nine lectures presented by the physiologist Edward Castle. The tall, thin Castle was bright but sad, habitually seen hurrying home by bike early each afternoon to a wife long stricken with multiple sclerosis. His lectures were a time warp back into the thirties. After listening to his opening talk, I could not have preserved my sanity listening to another. Three weeks later, before the same one hundred students in the Geological Museum auditorium, my first words were a promise that they would hear nothing more about the rabbit. The loud laughs that roared back assured me that I had broken the ice. After my last lecture, which was to be about cancer, I took Diana de Vegh to Henri IV, the French restaurant on Winthrop Street just off Harvard Square, run by the formidable Genevieve McMillan.

Genevieve had masterminded the transformation of a modest wooden house into a popular space to have stylish French food with conversationally inclined companions. Looking into Diana's big eyes, I was in high spirits, for my lectures had gone well, with my impromptu attempts at humor appreciated.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.