James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Initially I hoped to effect my social integration into the Harvard scene by living in one of the large undergraduate residence halls. Called houses, their creation realized President Lowell's wish to establish between Harvard Yard and the Charles River replicas of the Cambridge and Oxford colleges. As such, they would have young unmarried “tutors” living in specially designed suites. I asked my departmental chairman, Frank Carpenter, about the possibility, and he advised I try Leverett House, where the master was the embryolo-gist Leigh Hoadley. Though he had long given up even a pretense of being a scientist, I saw no reason to assume Leigh would prove equally useless as a house master. All too soon, however, I discovered that the “bunny hutch,” as Leverett House was then known, was never a first choice for undergraduates and that its so-called high table was the

antithesis of what I had known in Cambridge. We ate the same uninspired food as the undergraduates, and conversation followed the lead of Master Hoadley, incapable of either levity or deep thought.The ersatz high table might have mattered less if I had been provided with adequate living quarters. But my so-called suite did not look out on the Charles, its only view being to the opaque bathroom window of the master's apartment. My psyche was not helped by Hoadley's later admission that he might have given me accommodations more appropriate for a dog. I saw no reason to immediately let him know when I moved to a one-room flat carved out of a large house on nearby Francis Avenue. My first lab assistant, Celia Gilbert, daughter of the radical journalist I. F. Stone, had told me that her father's friend Helen Land had a vacancy nearby. It was one of several such small flats that I later realized were rented mainly to individuals with leftist connections. As I moved in, the journalist-to-be Jonathan Mirsky was moving out of the same building. His apartment was later occupied by a government graduate student, Jim Thomson, whom I would later meet when he became a member of the National Security Council.

In coming to Harvard still unmarried, I was more than conscious of goings-on at the once quite separate women's college, Radcliffe. Its residence halls were less than a mile away, and after the war classes at both colleges became entirely coeducational. Only the undergraduate Lamont Library remained out of bounds for women. How to go about meeting Radcliffe girls was not obvious, as their occasional mixers, then called jolly-ups, never seemed to bring forth the ones you would want to be seen with. Luckily, the geneticist Jack Schultz had a daughter, Jill, whom I had known earlier in Cold Spring Harbor, and who was now a Radcliffe senior living in a small wooden house off campus on Massachusetts Avenue. Soon I was to meet several of her housemates and gradually acquired the confidence to show up unannounced for after-dinner coffee.

Eating by myself in the faculty club was never an event to be anticipated and so I always greatly welcomed invitations to dine with the Dotys, now living less than a thousand feet from Paul's lab in a huge mansard-roofed house on Kirkland Place. Equally important in maintaining my morale were dinners at Wally and Celia Gilbert's equally

proximate flat. We had met the year before at Cambridge University, where Wally had gone from Harvard as a young theoretical physicist. Knowing that they soon would be going back to Harvard upon completion of Wally's Cambridge Ph.D., I offered Celia, who had been an English major at Smith, a job at my lab starting in the fall. With Celia about, even routine lab manipulations became moments of conversational mischief. But after only four Biolab months, she was struck with mononucleosis. Her illness ended her tenure in my lab and, perhaps as a small consolation, the anxiety she suffered when called upon to dilute phage solutions by factors as big as a million.Subtle conversational moments returned in March when Alfred Tissières, with his Bentley, arrived from Cambridge. Soon finding himself a room in a house off Brattle Street, he took on the task of finding a lab technician to replace Celia. Happily, Kathy Coit, whose parents were now housing Alfred, expressed interest in joining us. Finding her not only intelligent but also an enthusiastic rock climber, Alfred persuaded her to become our factotum. Though this was her first exposure to science, Kathy's cheerful common sense soon made her indispensable to our day-to-day lab progress.

Covering Alfred's salary was a grant that I had obtained from the National Science Foundation to study the ribosomes of bacteria. Those funds also allowed us to buy a preparative Spinco ultracentrifuge needed to spin them away from other bacterial components. A more expensive analytic Spinco that could measure how fast ribosomes sedimented was needed, too, but my grant wouldn't stretch that far. Luckily, we had one at our disposal thanks to the protein chemist John Edsall on the floor above.

Most evenings I would be back in the lab, having already spent the daylight hours there. After hours, we were required to sign the night watchman's sign-in book. There was no good reason for its existence except catching an errant husband in a lie concerning his whereabouts of an evening. One night I entered and was pleased to find it had gone missing, with no untoward consequences for the building's proper function. More frustrating was the bolting of the departmental library when the dour librarian went home. Though faculty members had keys, graduate students didn't and could not search out

journal references in the evenings or on weekends. My continued pestering for the department to pay students to guard the entrance finally led to that reform for the common good.

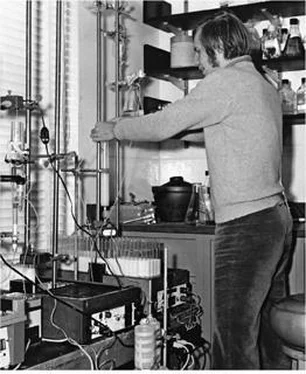

Harvesting tobacco mosaic virus in 1958. From left to right: Julian Fleischman, Kathy Coit, John Mendelson, and Chuck Kurland

Nathan Pusey regularly opened Harvard's stately President's House to his faculty and their spouses for Sunday afternoon tea and cakes. Paul Doty urged me to sample such an occasion, and I semiawkwardly presented myself at the front door when my fall term lectures were nearing their end. Led by a maid into the main drawing room, where I introduced myself to the Puseys, I soon was passed along to talk with the late-thirtyish Swedish theologian Krister Stendahl and his equally youthful wife, Brita. A prize catch in Pusey's efforts to resurrect the Divinity School, Stendahl had a strong, angular, slightly distorted face that struck me as that of a troubled minister in an Ingmar Bergman film. Liking his reasoned openness to the complexities of human life, I nevertheless could not even affect interest in the Evangelist Matthew, about whom he had just completed a scholarly tome. Later, when

Anne Pusey moved to be near me, I felt much more at ease talking about my Chicago education and how fortunate I felt to be part of the Harvard scene. Simultaneously I tried to overhear what our president was saying to others. Later, as I walked out onto Quincy Street, I wondered whether any conversational gambit could possibly elicit from him an animated response.Later during the monthly meetings of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, I was no more successful at discerning the feelings that occupied what he considered to be his soul. We always turned to Bundy for hints of what was coming next. Pusey seemed to come to life only when presenting honorary M.A.'s to those newly tenured faculty whose actual degrees had been conferred elsewhere. Through this gesture of sanctification, Harvard saw itself as ensuring that all faculty felt equally valued.

My social life at Harvard still left much to be desired. I had flown to London just before Christmas, and then for the New Year had gone by train up to the home of Dick and Naomi Mitchison on the Mull of Kintyre in the Scottish Highlands. My first visit to their Carradale House had been five years before, when I was invited by their youngest son, Avrion, then doing his Ph.D. thesis in Oxford on the immunolog-ical response. Av's mother was a distinguished writer of leftist persuasion, so I could again count on being part of an intellectual house party that featured long walks over boggy moors, heated conversations much more about politics than science, and hearty but never inspiring food. Still, I knew it would be much more fun than going back to the small home in the Indiana sand dunes to which my parents had moved after my sister's graduation from the University of Chicago. I would later regret not having been a more dutiful son when my mother, only fifty-seven, died of a sudden heart attack not long after the holidays. She never had the pleasure of visiting Harvard to see me as a member of its faculty. When I went home for her funeral, I could see my father was unlikely ever to recover entirely from her unexpected death.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.