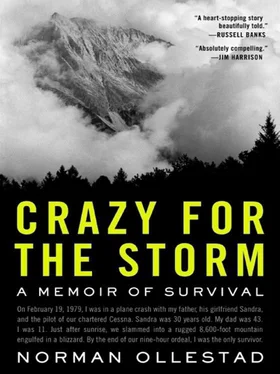

Ollestad—we can do it all, he said.

He opened his arms as if offering me the valley and the forest, maybe the entire world.

It was snowing hard and the nightlights finally reached full glow when the course setter announced that the gates would be loosened up a bit because of the conditions. My dad groaned. Among the coaches and parents gathered around the race department, he was the only person unhappy with the decision. My chances were whittling away.

I heard Lance McCloud’s name when I got to the starting tent and I circumvented the crowd and finally saw him. He was a small boy like myself and he wore a spiffy ski team suit and all his teammates listened intently as he spoke. His coach sharpened his edges and waxed his skis and I watched him stretching and joking with his friends, comfortable and relaxed. My dad kneeled beside me and reviewed the gates with me, then he looked over my skis like he was going to tune them up but we didn’t have any files or wax with us.

Lance raced second and nobody else was close to his time. Finally they called my number and I poled nervously into the starting gate. The starter counted down—five-four-three-two-one-Go!—and I kicked off the pad and broke the wand. Instinctively I banked on two skis into my first turn, powder style. The rut was filled with snow and I felt my skis spring me into the next turn. I sailed through the pillowy ruts as if skiing powder bumps. It was not something I had planned and I questioned what the hell I was doing. But I didn’t have to jam the edges and the skis sliced right through each turn, running well.

I crossed the red dye of the finish line and the first thing I saw was Lance McCloud’s face, twisted with envy. I knew I had beaten him. Checking the board I had the best time by half of a second. My dad appeared and waved me over.

Pretty good, Ollestad, he said in front of the leering crowd. And we skied away.

We waited in the starting tent for the second run to begin. Lance’s team kept their backs to us and whispered to each other. A couple boys from Squaw Valley and Incline Village congratulated me and I thanked them. My dad didn’t say a word. The kid who finished twentieth went first. I would go last. My dad hiked over to the starting gate and when he came back he was shaking his head.

What? I said.

They got a whole team of people scraping away the snow in the ruts.

Why?

Why do you think?

Oh, I said, understanding that it was for Lance. He must not like powder.

When it was Lance’s turn the tent got real quiet. I was right behind him and could see the army of people on the course side-slipping the fresh snow out of the ruts, making the course faster. Then Lance charged off the starting pad and I couldn’t see him through his vapor trail.

They’ll be a little choppy this time, said my dad before he kissed me and told me to have fun.

When I crouched in the starting gate I noticed that the army of rut-cleaners was gone. The ruts were filling with snow and that would slow me down. Everybody was supposed to have similar snow conditions to level the field. The course was faster without snow in the ruts, so Lance had had a huge advantage on his run. A few gates lower I saw my dad waving his arms and yelling at one of the race officials. Then it was time to go.

The first rut took me by surprise. I had too much edge, too hard an angle, and my skis plowed into the snow. I jerked my knees up and out and was in the air, another tenth of a second lost. By the third turn I was back into my powder rhythm. As I moved into the flats the snow felt deeper and I did everything I could to glide instead of sink. The crowd roared as I came over the finish line and I knew I had lost.

I came to a stop and looked for him. Lance was somewhere inside the hustle-and-bustle and I checked the board. His combined score was two-tenths of a second faster than mine, meaning he had beaten me by a healthy seven-tenths on the second run. My dad skied up beside me and he whistled and his face was dimpled.

Done good Boy, he said.

I got the chills when they called my name to the podium. I stood to Lance’s right and they hung the silver medallion over my neck. Afterward strangers shook my hand and my dad spoke to one of the coaches from Incline Village, a tall Swede wearing clogs.

He wants you on their team, Ollestad.

Really?

Yeah man. And guess who he’s friends with.

I shrugged.

Ingmar Stenmark.

We were in the corner and I looked across the room and saw the Swede’s head poking out from the crowd. Ingmar Stenmark was the greatest skier ever and my whole body inflated.

Tomorrow you’re going to train with them, said my dad.

I was speechless.

Way to go, Ollestad.

Then the Heavenly Valley coach interrupted us.

Congratulations on taking second place, he said to me.

I nodded and my dad nodded.

You got pretty close. Lance had to take it up a notch on the second run, said the coach.

Yep, said my dad.

The coach waited as if expecting more from my dad.

I looked at my dad, come on, say it: Why didn’t they slide the ruts for Norman?

We’ll see you next month, was all my dad said.

The coach patted him on the shoulder and walked away. My dad never did mention their shenanigans and the following day I trained gates with the Incline ski team. Coach Yan gave me lots of attention, working with me on the hip-thrust weight change that made Ingmar so dominant. The other kids treated me with a respect I had never experienced and I was careful to be humble and not act like I was something special.

Sunday afternoon my dad and I left Tahoe and I had a new ski suit, padded sweater and all. When we passed the Heavenly Valley turnoff my dad said,

They’ve heard of Waterman now, Ollestad.

SANDRA’ S WEIGHT PUSHED down on my shoulders as I cleated the thread of snow along the base of the rock wall. My whole body quivered with exhaustion. A tree limb appeared from the rock wall and I reached up and grabbed it. Sandra settled onto my other hand, nearly too small for her boot. Not clinging by fingernail, chin, pelvis and toe-tip was a huge relief. We did not speak, just resting.

It was time to move on. I told her we were almost there even though the chute did not seem to end, ever. The thread of snow would thin every few feet, making every inch without slipping a triumph. Having to hone my concentration blocked out the fact that we were moving too slowly and that night was only a couple hours away—that we were still, after all this time and effort, near the top of the mountain, thousands of feet above the meadow.

Locked into a pace, disciplining myself to be grateful for the progress, time passed, until I realized Sandra’s boot was no longer touching my numb shoulder. I tilted my head to find her ankle. Not there. I looked up.

I was three or four feet below her. Both her arms reached high as if she were stretching out to sleep, even stranger because she was in a nearly vertical position.

Sandra. Get the stick down, I ordered. Push to your left.

She drew her knees under her stomach as if trying to stand up.

No, I yelled. Stay down.

From her knees she toppled over and plunged into the funnel, her limbs clambering as if trying to run uphill.

With my left hand I jabbed the withered stick into the snow. I reached for Sandra with my right hand. As I reached, her trajectory into the funnel shifted, routing her straight down. Her fingers struck my bicep and then her body plowed over me. I saw my hand grope her fancy boots—too far below me suddenly. She rocketed headfirst into the center of the funnel.

Norman! she screamed.

I was sliding too and I reached with my other arm and blindly grabbed a tree poking from the rocks.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу