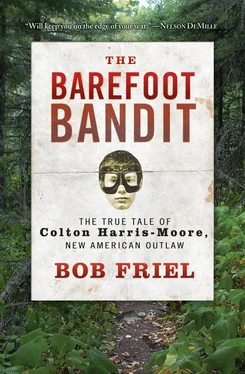

The Great Recession was as fertile a ground for Colton Harris-Moore to emerge as an outlaw hero as the Great Depression was for John Dillinger. The Internet and social networks simply ensured that Colt became a world-famous outlaw at warp speed compared to all those who’d gone before him.

Even though Dillinger and his gang went on a tear across the country that left a dozen dead—including cops and bystanders—people rallied to him just as they would seventy-five years later to Colt, who was much, much safer to root for because he hadn’t physically hurt anyone. In Dillinger’s Wild Ride , Elliot Gorn quotes people of the gunslinger’s day venting in ways remarkably similar to Colt’s Facebook defenders about what they saw as a corrupt system rigged against the common man. “If folks had jobs and could feed themselves, if government protected citizens from the banks that preyed on them… they wouldn’t make heroes of men like Dillinger.”

According to professor Graham Seal, author of The Outlaw Legend and one of the world’s foremost authorities on outlaws both historical and in folklore, to break into the pantheon of great outlaw heroes, the person must go beyond common criminality. “He needs a few actual or mythical characteristics, such as the ability to elude capture… and he needs a bit of style.” Colt had all that, plus a sense of humor, which always helps.

Americans like to believe that our national character still includes a little bit of the frontier outlaw. And compared to most outlaws, Colt was easy to get behind. He was a clean-cut rural kid who was nonconfrontational and hadn’t killed anyone yet. The most repeated plea on his Facebook pages was “Don’t hurt anyone!”

In all outlaw stories, though, the victims are forgotten. They get in the way of the fun, and the outlaw’s fans prefer they’d just exist in the background with their hands in the air. Stopping to look at them slows down the tale and risks impugning the character of the sympathetic bandit. In Colt’s case, some of his supporters caricatured and dehumanized the victims simply as “rich people” and thus somehow deserving of having their stuff and their security stolen. The fact that Colt also stole from middle-class folks and those running mom-and-pop businesses was an inconvenience best ignored. The last refuge was the “So what? They’re insured,” rationalization, obviously made by those who’d never had to deal with an “insured” loss.

ON DECEMBER 16, 2011, Colt stepped into an Island County courtroom to face sentencing for thirty-two Washington State charges. Judge Vicki Churchill, the same judge who sentenced Colt in 2007, presided. Colt’s attorneys filed a mitigation package that presented a narrative of Colt’s early years. It was the most damning report yet of his mother’s “toxic presence that shaped his childhood.” Much of it was in Colt’s own words: “My mom is also a heavy alcoholic… No question that her entire life, house, family and friend relationships have been ravaged by her alcoholism.” Colt talked about Gordy Moore, too, recalling an argument in the trailer about child support payments, when Gordy “literally picked my mom up and threw her across the room,” the event that Colt says Pam claims is when she broke her back.

A large part of the defense’s argument for granting Colt leniency was based on the assertion by the psychiatrist Dr. Richard Adler: that Colt suffers from Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. The diagnosis was based on numerous neuropsychological tests and on the testimony of Pam Kohler’s brother, Ed Coaker. Coaker said of Pam, “When Pam drinks one beer she gets mean, and when she drinks two beers she wants to fight. But, Pam drinks twenty beers… she would drink until she couldn’t hardly walk.” Coaker admitted to drinking with Pam while she was carrying Colt and claimed “her pregnancy didn’t affect her drinking whatsoever.”

The other revelation from Ed Coaker was his claim that Pam had met at least two of the men who shared the trailer with her and Colt, including Bill Kohler, through prison pen-pal programs.

The mitigation report also took the state CPS system and Stanwood-Camano school district to task for letting Colt “fall through the cracks.” Dr. Adler notes that “All of the CPS investigations were closed in short order, ironically due to mother’s lack of cooperation.”

Colt says he loves his mother and wants her to be happy. Her alcoholism, though, “is the number one, and as far as I am concerned, the only problem my mom has that prevented a friendship with me.” As of press time, Colt has been in Seattle for seventeen months, but has not yet seen Pam.

ON THE WASHINGTON STATE side of things, Greg Banks from Island County and Randy Gaylord from San Juan County told the judge that they’d taken Colt’s rough childhood and his nonviolence into account in recommending that she give him the high end of the sentencing range: nine years and eight months.

After the prosecution and defense had finished their presentations, Judge Churchill recessed for twenty minutes then came back into court and made a remarkable speech:

I think this case is a tragedy in many ways, but it’s also a triumph of the human spirit. I sympathize with the defendant due to the terrible upbringing he had. As one investigator indicated, “it was a mind-numbing absence of hope.” It was a tragedy he had to steal food… to endure the taunts and jeers of classmates… that he had an alcoholic and abusive mother… We can all shake our heads and wonder how did this all happen, and more importantly, how can we keep it from happening to another child?

Judge Churchill said that in reviewing Colton’s upbringing and the psychological reports of his mental health issues, “I was struck that I could have been reading the history of a mass murderer… I could have been reading about a drug-addicted, alcoholic, abusive young man who followed in the path of his mother. Yet I was not reading that story. That is the triumph of Colton Harris-Moore. He has survived.”

Sitting in the courtroom, it felt like the judge was about to let Colt walk out a free man or maybe give him a medal. But there came a “nevertheless… ” Judge Churchill said she was elected to uphold the law, was bound by the state’s sentencing reform act, and needed to protect the public. She acknowledged that “Mr. Harris-Moore has an extensive criminal history, and a high offender score.” She said, though, that because she felt he was remorseful, contrite, and because he was paying full restitution—“something that is unique in cases like this”—she would give Colt the minimum sentence allowed within the standard range: seven years and three months. She ended with, “I wish him well.”

Colt, who was ready to accept the max, was happy and relieved with the judgment. Churchill tacked on the $292,167 in restitution owed to the San Juan and Island County victims, and Colt was taken away.

Colt’s federal and state sentences will run concurrent, but the state clock does not begin counting down until he turns twenty-one on March 22, 2012. With time off for good behavior, he could be stepping out of a Washington State prison in time for his twenty-fifth birthday.

* * *

UP HERE IN SAN JUAN COUNTY, Sheriff Bill Cumming decided not to run for another term. After a tough, mudslinging election, voters chose new blood in fifty-one-year-old Rob Nou, who says his policy is that deputies should collect forensics from every crime scene possible.

Unsurprisingly, the crime rate on Orcas Island dropped after Colt left. I suspect that it might remain even lower than what it was before he arrived. Because of Colt, residents are much more conscious of the potential for crime. Many homes and almost all businesses are wired with burglar alarms and surveillance systems. Unfortunately, the relaxed, open-door atmosphere is a thing of the past.

Читать дальше