I put away the pistol and drove home. That night, I experienced no sudden change of direction to my life. I didn’t know where I was headed in the future, but I knew quitting wasn’t right. Not that night, not ever.

Did the PTSD clinic make a difference in my life? Yes, it did. I’m still here.

I had a good job with a company testing new gear for the military. The work interested me and I was good at it. But at night I was still drinking myself to sleep until Toby and Ann introduced me to Chris Schmidt, the dean of our local college.

Chris was a no-nonsense guy who didn’t care about what happened in the past. I lucked out, though; his dad had been a Marine and he had almost volunteered to be a grunt. All he wanted to know was what I was doing today, tomorrow, and the day after that. His solution to problems was to set up a daily routine to overcome them.

He took me into his small bicycle group that hit the roads daily for ten or twenty miles. It wasn’t just the exercise; as a group you had to look out for each other on the curves and keep an eye on the traffic. Each rider had to pitch in and was accountable in his own eyes and in the judgment of the group.

I liked that. In some ways, it was like being back at Monti with the team. I had come back to the farm as a loner. That hadn’t worked. I wasn’t holding myself accountable. In a team, you care about the other guys and don’t want to let them down.

* * *

I didn’t want to let myself down, either. I was proud that I had served my country and I appreciated all the Marine Corps had done for me. That summer, I took classes at our local college. During one class, a professor told us that we had lost the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. When I challenged him to explain why, he said we hadn’t accomplished anything. “We fought for nothing,” he said. “I’m a Vietnam vet, and I know the feeling.”

“I served in Iraq and Afghanistan,” I said, “and I don’t know the feeling. I’m not going to sit here and let you say my guys died for nothing.”

The professor believed the Taliban would take over Afghanistan when we left. I didn’t look at it in those black-and-white terms. No one can predict how Afghanistan will turn out years from now, and I’ll leave it to historians to sort out the mistakes.

We invaded in order to destroy the terrorist network that had murdered three thousand civilians on 9/11. We’re safer here in the States than in 2001 because we took the war to the jihadists and didn’t play defense inside our own borders. I was fairly worked up by the time the class ended. The professor later apologized, saying he came across stronger than he had intended. I told him I could be a little hard-headed myself.

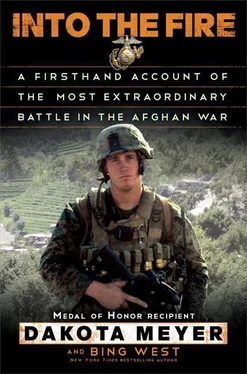

In August of 2011, a Marine colonel alerted me that the White House was reviewing my award packet and might call me. About two weeks later, the White House operator called. I had switched jobs and was pouring concrete. It was hot, noisy work and I could barely hear. So I asked for a call-back in forty-five minutes. My boss said I could take my lunch break early. I hurried over to the local convenience store, grabbed a Coke, and answered the next call on the first ring.

“Dakota? This is Barack Obama,” the president said. “I have just finished reading about the battle and have signed your citation for the Medal of Honor.”

For a second, I thought it was a joke. I never expected the president’s to be the first voice that I heard, let alone that he would introduce himself by his first name. I stood at attention as I spoke to him. The construction crew had followed me over to the store. I’ll never forget their expressions when I gestured to them to quiet down while I talked to the president of the United States.

In September, I flew to Washington. The day before the ceremony, I had half-jokingly said to a White House aide that I’d like to have a beer with the president. When I said that, I didn’t mean to be pushy or flippant.

That evening, I sat in a chair outside the Oval Office looking at the Washington Monument and sipping an ale with the most powerful man in the world. It was irrelevant that my political philosophy was quite different from his. He was my commander-in-chief, and he was extremely gracious.

“What’s on your mind, Dakota?” the president said.

I told him I didn’t have any idea what to do with my life.

His advice was to never stop studying and learning. Education was a lifelong undertaking.

He also observed how he missed the normal things in life, like going to the store to buy shaving cream. He was my commander-in-chief, and he was conveying what was expected of me. I understood his subtle message. I’d have to be extra-careful whenever I drank, or said something when I went out with my friends. I was expected to represent with dignity those who had gone before me, who had given their lives and who had been terribly wounded.

The next afternoon, I returned to the White House for the ceremony. When the president hung that medal around my neck, I felt glum. I couldn’t smile and I said nothing. I gave no remarks and avoided the press. As a Marine, you either bring your team home alive or you die trying. My country was recognizing me for being a failure and for the worst day of my life.

In attendance were other Medal of Honor recipients, generals and politicians, friends and relatives, and my comrades-in-arms. Rodriguez-Chavez and his wife were there with his beaming daughters, as were Swenson, Kerr, Bokis, Devine, Jeffords, Skinta—and on and on.

The president hosted us in the East Wing, where kings, prime ministers, ambassadors, and Hollywood stars were normally welcomed. The setting spoke to the history and traditions of America. In the Blue Room hung George P. A. Healy’s finest presidential portrait. In the East Room, Gilbert Stuart’s painting of George Washington hung above the fireplace. Ben Franklin was on the far wall of the Green Room. The White House seemed almost a living thing, full of power, dignity, and tradition.

Sgt. 1st Class Leroy Petry, awarded the Medal of Honor a few months earlier, showed us how he could rotate his prosthetic right hand. He had lost his hand in Afghanistan throwing back an enemy grenade.

“Why didn’t you pitch the grenade away with your left hand?” someone asked him.

“I can’t throw lefty,” Petry said. “I’d have blown up my buddies and me!”

We all laughed. Here we were—Army and Marine grunts in uniforms with ribbons from a dozen campaigns—drinking beer in rooms accustomed to diplomats and senators. Where else in the world would the head of state welcome into the halls of power, pomp, and history simple warriors who had no political connections or financial riches?

The Marine Commandant, Gen. Jim Amos, and Gen. Joseph Dunford attended the ceremony. Throughout the years after Ganjigal, the Marine Corps leadership had provided consistent support not just to me, but to all who had fought there. The top enlisted man in the Marine Corps, Sgt. Maj. Mike Barrett, twice came to our farm to meet my dad and granddad and to encourage me.

There is no such person as a former Marine. Fifty years after they have left active duty, Marines still sign emails to each other with S/F—Semper Fidelis . Always Faithful. Of course we have among us those who fail themselves, their families, and society. The fact remains, though, that the Corps expects every Marine to live by a set of core values. In turn, the Corps keeps its side of the bargain. You cannot ask anything more of an organization than that.

The Medal of Honor, given in the name of the Congress of the United States of America, symbolizes the courage and determination of our entire country. I think if the president hadn’t said what he said, I wouldn’t have been able to stand it. But I met great people, and still do.

Читать дальше