The whole deal pissed me off, being cooped up behind the wire, playing defense and buying time. For what?

A few days later, a farmer showed up on base to complain that bullets had struck his chicken coop. The date matched when I had fired the .50-cal. The farmer claimed he lost five hens.

The civil affairs officer gave him two hundred dollars—forty dollars for each scrawny chicken. The sniper on the farm tries to kill us, and we pay extortion?

Before dropping a shell down a mortar tube, the gunner levels the bubbles on his sight. If he loses the bubbles, then the tube is pointed at a crazy angle. Forty dollars for a chicken? The figure went around and around in my head. After Ganjigal, I was losing the bubble.

Standard procedure after an engagement: investigators gather sworn statements. The defeat at Ganjigal generated a lot of paperwork. I wrote a few paragraphs, as did the others. Sgt. Maj. Jimmy Carabello, the top enlisted man in Battalion 1-32, took a personal interest in the battle and reviewed the statements.

I didn’t care what happened one way or the other, as long as I stayed far out of his way. Carabello reigned supreme on Joyce. Every soldier in the battalion had a Carabello story. He meted out punishments like ordering a soldier to write a two-thousand-word essay on “Why I should not roll my eyes when my sergeant tells me to do something.”

He built a hooch with a veranda where he smoked his cigars in the evening, watching basketball games on the court he’d built a few feet away. He thought the soldiers spent too much time by themselves on their iPods, so he insisted every unit on base field a team.

That wasn’t enough. He wanted his soldiers to see real, beautiful cheerleaders. He contacted the USO agent for the cheerleaders for the New England Patriots, who were on tour in the rear. Somehow he persuaded the agent to book an afternoon tea at Joyce with his soldiers. The event went smoothly until a warning via radio intercept. Carabello and the soldiers waved good-bye to the cheerleaders half an hour before rockets slammed into Joyce.

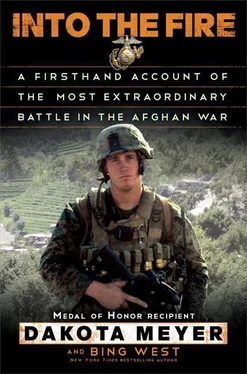

When the sergeant major put his mind to something, you couldn’t deflect him. Somehow, after reading the investigation statements, he decided to assemble packets recommending Will Swenson and me for the Medal of Honor. My packet was sent up the Marine channel and Swenson’s up the Army channel. I didn’t care and neither did Swenson. We were both getting out of the military and we were both furious about Ganjigal.

I’d heard there had been a hasty investigation about Ganjigal that found some shortcomings and “poor battle management” by a captain in the TOC at Joyce. That was a whitewash by higher headquarters, called Joint Task Force 82. It was like saying Lincoln was assassinated because an usher left a theater door unlocked.

My boss, Maj. Williams, had put out the word not to talk to the press. That made sense. I had assumed headquarters would cover for themselves. And why should there be any medals when my team was dead? The hell with it all.

I was up at Monti, far from anybody or anything. My only thought was how to get three hours’ sleep so I could function the next day. In return for a forty-dollar chicken, I deserved to shoot somebody.

I walked into my hooch one October day to find a journalist chatting with the other advisors. He had just returned from an operation with Lt. Kerr, who had insisted that he talk with me. We had barely shaken hands when the base took some incoming and I left to check things out. Later that day, I bumped into the writer again.

“One question before I leave,” he said. “Any truth to those stories that you were left on your own at Ganjigal?”

“My team would be alive today if we’d gotten artillery,” I said.

“You’d tell that to the high command? You’d say that to a general?”

He was straight up about it. I knew that what I said next would be reported high up the chain of command. Maj. Williams—and probably a lot of others—would be furious that I spoke out as a corporal without informing them first. I understood what I was doing before I replied.

“I’d tell that to any general,” I said. “We were screwed.”

Once I said it, I felt relieved. I had told the truth, the way my dad and the Corps had taught me. Swenson and others had said the identical thing in their statements that were first hidden from public view and later heavily redacted. I knew there would be repercussions for speaking out publicly.

But I didn’t expect a few weeks later to be told the Marine general in charge of Afghanistan was flying in to have lunch with me. He was also scheduled to meet privately with Capt. Swenson. I didn’t need to be a genius to know that Ganjigal would be the subject.

Lt. Gen. Joseph Dunford was easy to talk with. He had a quiet presence and seemed to know everything about infantry tactics. He was interested in what I thought about dealing with the Askars. I told him that I thought that the American advisors should be infantrymen, and I told him that we were let down at Ganjigal. When we call for fire, we deserve to get it. He didn’t ask one word about the investigation and never expressed an opinion, one way or the other. He just listened and left.

I later learned that the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Gen. James Conway, was furious about the superficial nature of the JTF-82 investigation. He believed his Marines had been let down, and he let his feelings be known. Joint Task Force 82 was the command above the advisors and Battalion 1-32. JTF-82’s commander, Army Maj. Gen. Curtis Scaparrotti, ordered a second investigation, jointly conducted by a Marine and an Army colonel.

I wasn’t asked to testify. In late November, the two colonels submitted their findings that eventually were published on the Internet with all names blanked out. Gen. Scaparrotti said the lessons learned had been sent to his subordinate commands. Up at Monti, I never heard one lesson.

The fuzziness of the investigations angered me, but I was running on autopilot—training Askars, taking naps, and advising on a few missions outside the wire. My Afghan company—down to fifty-six men—was going through the motions with us advisors. They knew it and we knew it. I got along fine with the Askars, but they were mostly a different bunch. What with Ganjigal and the usual monthly turnover, less than a dozen were left from our high-spirited crew of last summer. It was a different atmosphere with a different group of Afghans. Those who survived Ganjigal were scattered, mostly gone from the army.

We advisors had lost clout because we couldn’t get fire support—that was obvious. After Ganjigal, our Afghan battalion commander insisted on joint patrols, with each Askar close enough to grip the belt buckle of an American soldier. My days of hopping behind a .50-cal and driving into a different village each day had come to an end. Except for an occasional foray, we abandoned Dangam.

I did enough chores to keep me busy during the day. At night, the mental barriers of being awake crashed down and the demons crept in. I didn’t want to sleep. The Army psychologist I had bumped into down at Joyce kept visiting Monti. She claimed the visits were routine; I knew better. She was talking to some of my friends about me. She had a quiet way that encouraged men to talk, and some felt I was tightly strung after Ganjigal. I didn’t want to discuss my feelings with her.

She sent me twice to a psychiatrist back in Jalalabad. There was this theory called ego depletion. As explained to me, the brain gets depleted after making too many hard decisions. In extreme cases, the mind shuts down and refuses to make decisions. That’s called shell shock. That wasn’t me. Or the brain takes shortcuts and acts impulsively. That’s called reckless behavior. Maybe that was me, a little.

Читать дальше