“This is bullshit, Rod.”

I rechecked the ammo belt on the Mark 19. Rod sat in the driver’s seat.

“You ready, Rod?”

“Give it a few more minutes, Meyer. You’ll fry for this,” he said.

He was right. I’d get sent home for disobeying a direct order. There was no question in my mind about that. I was already on thin ice with Garza, Fabayo, and Williams. So I sat there, frustrated, listening to the shooting, flexing my hands on the grips of the Mark 19 and breathing hard. I tried to calm down. Maybe the battle sounded worse on the radio than it really was. Son of a bitch!

Inside the tactical operations center at Joyce, Capt. Aaron Harting was the senior officer on duty from midnight to eight in the morning—the battle captain. He had been in Afghanistan for eight months but had rarely controlled fires, and certainly none like this one.

His desk was behind a low railing at the south end of the large, square white plywood room. A big electronic map and several video monitors—the eyes in the sky and other sources—were mounted on the north wall. A forest of electronic green boxes and flat-screen monitors were jammed in. Rough plywood shelves held three-ring binders; weapons leaned in plywood stands. Flip-chart easels and chalkboards and whiteboards, water bottles, an electronic coffee-maker, foam cups, bundles of cables going through holes in the walls, paper topo maps taped to walls, exposed air ducts, digital wall clocks with local time and Zulu (Greenwich Mean) time, and soldiers with short haircuts and camo clothing filled all the visual space. Between the electronic map wall and Harting was a long desk with computer screens and radios manned by the half-dozen or more sergeants who daily tracked unit locations and fire missions.

As artillery stood by at Joyce and at Asadabad, a few miles away, Harting asked for more and more information from the men on the long table: Who was requesting the fire missions, was it Shadow 4, Highlander 5 (Swenson), or Fox 3 (Fabayo)? What had they heard from Fox 6—Maj. Williams? Who was presently in charge, the Marine advisors or the Afghan Army? Did the ground commander know where all his troops were? Had they double-checked the grids of the KEs?

He asked question after question.

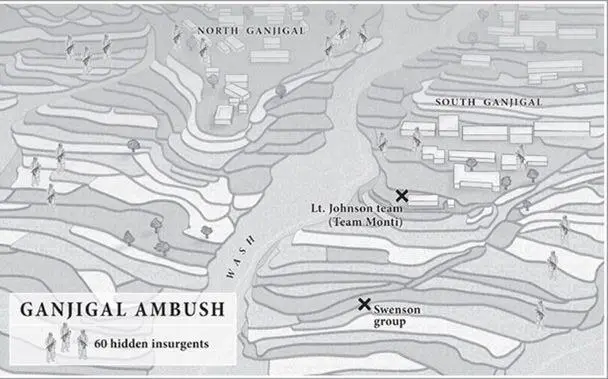

In the valley, Swenson dodged his way forward one hundred meters to link up with Fabayo, who was calling artillery in on KE-3345, near an enemy machine-gun location, four hundred meters to the east.

At Joyce, 120-millimeter mortars were fired fifteen minutes after Fabayo requested. The first shell, though, struck within fifty meters of the enemy position. The next flurry of shells was on target. That would be the only effective fire mission of the entire day.

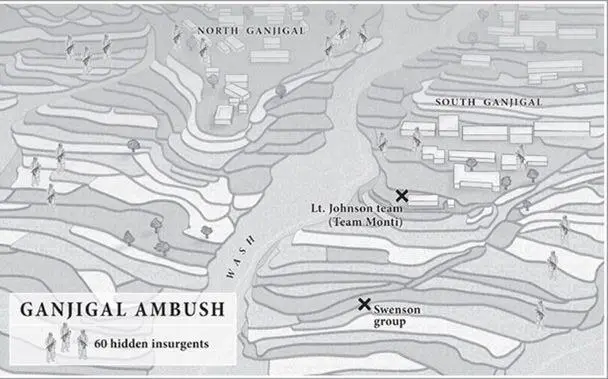

The patrol was now in deep trouble. The ridgelines on the horseshoe around them were a tangle of rocky outcroppings and shallow caves. Enemy machine guns, three hundred to six hundred meters east of the patrol, were nestled into snug crevices, far enough back to conceal gun flashes, with angles of fire that crisscrossed the valley. The only cover was the retaining walls of the farm terraces on either side of the wash.

The TOC had recorded Swenson’s first request for fire—the “Undo KE”—at 0537. Eventually that request was sent via computer to the 155-millimeter artillery battery at Asadabad, about four miles away. A well-trained artillery battery has shells in the air less than three minutes after a call for fire. It wasn’t until twenty-three minutes later that the guns at “A-Bad” fired the mission.

Fabayo grew infuriated by the lack of support. Shifting to another KE, he heard the shells hit in a draw. He made three more adjustments, but hitting a hidden target somewhere on the uneven side of a cliff requires long practice and a prodigious number of shells—and time, which they didn’t have. The machine guns kept firing.

Lt. Johnson and the rest of Team Monti had taken cover in a house on the edge of South Ganjigal, while the Askars caught in the open wash scrambled for cover. The enemy above them worked their way around the edges of the valley. Shooting downhill, the Taliban machine-gunners tracked in on one Askar, then another, then another. It was a killing ground.

Swenson, still with Fabayo, plotted another fire mission. They called artillery on KE-3365, a spot above and to the right of South Ganjigal where the enemy’s heavy guns were firing. Swenson and Fabayo had identified three enemy machine-gun positions, if they could just get some shells to land on them.

A few meters in front of the two men, an Askar screamed and crawled away, seriously wounded. Two other Askars ran by. Behind them, another yelled, dropped his M16, and limped down the draw. Fire was coming from three directions, kicking up spurts of dust around the two.

They’re all over the place , Swenson was thinking to himself. I may not make it out of here .

When he wasn’t on the radio, Swenson was pointing out shooters to Fabayo, who shot at them with his M4. A few meters behind them, Maj. Williams and 1st Sgt. Garza were popping up and down, trying to provide covering fire, but the patrol was grossly overmatched. The enemy gunners were dialed in, and were delivering ten aimed bullets for every wild shot our guys were throwing back at them. Fabayo sensed that the angle of enemy fire was shifting to the southeast, a sure indication that they were being flanked—soon to be surrounded.

The Afghan operations officer kept asking Maj. Williams what he was going to do. For his part, Williams was hoping that air would arrive any minute to suppress the enemy gunners. The fiction that the Afghans were in charge had fallen apart.

Swenson wasn’t waiting for the majors to decide who was in command. He shouted at his police to move farther south to prevent being encircled. Within minutes, however, the police were pinned down and stopped returning fire. Not fighting back is the worst mistake you can make in a firefight. Men instinctively duck when rounds are zipping over their heads. Most firefights are standoff affairs. Each side tests and probes the other, backing off when meeting resistance. Few men press home an assault in the face of return fire.

But if you hunker down and don’t shoot back, you will surely die. The other side gains confidence and rushes forward. In the frenzy of combat, soldiers act like sharks. They sense weakness and circle in, picking off the wounded and the defenseless. Slowly the dushmen were closing in from both sides of the wash.

Kaplan, up on the ridge, passed Swenson’s fire requests to Shadow 4, the Army scout-snipers up higher on the ridge, at least seven times. Sgt. Summers at Shadow 4 kept assuring Kaplan that the fire missions were getting through, but…

“The TOC won’t clear the missions,” Kaplan radioed to Swenson. “The fucks won’t shoot the arty.”

Swenson had identified enemy positions at four grid positions. There are two basic ways of calling in artillery. You can give the grid coordinates of the target or the KE number for a grid, and adjust after the initial round. Or you can give your own location and a compass bearing and distance to the target. This second technique, called a polar mission, provides the guns with the locations of both the friendly observer and the target.

“Tell the TOC I’ll send it polar,” Swenson radioed to Kaplan. “It’s on me! Give them my initials. I’m making the decision, not them!”

Assuming accurate fire—the U.S. mortars were less than two miles away—the only target endangered by the polar plot was the enemy. By sending his initials, Swenson was taking full responsibility. If anything went wrong—if a friendly soldier or a civilian were hit—the burden rested squarely on Swenson, not with the TOC in the rear.

Читать дальше