Refusing to look at me, the man clicked away at the string of worry beads in his hands. When I tried to shake hands, he ignored me. I was surprised by the open insult. Even when they don’t like you, Afghans shake hands, just as Americans do. The teenager smirked. I stepped aside and they strode past.

“What you think, Homey?” Rod asked.

“This sucks,” I replied.

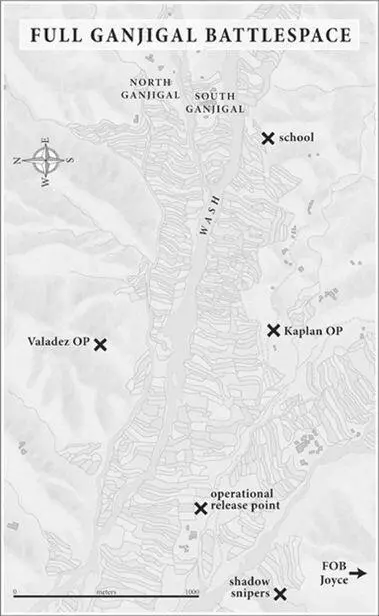

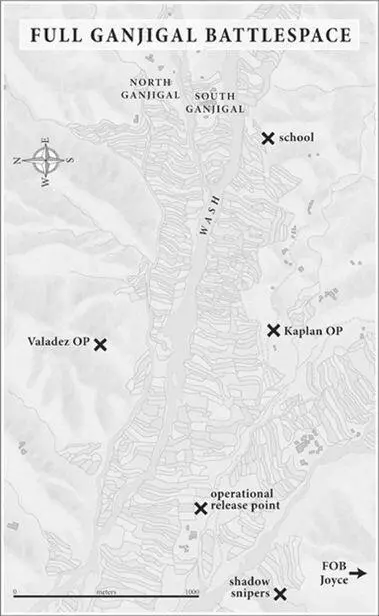

Team Monti and the lead platoon had climbed up a series of terrace walls and were entering the outskirts of South Ganjigal as dawn broke. They spread widely apart in the open terrain. Behind them came Majors Talib and Williams, 1st Sgt. Garza, and 2nd Lt. Fabayo. A bit farther back, Swenson was walking with some police, keeping within shouting distance of the others.

As Lt. Johnson approached the first row of houses, he radioed back to Garza that he and Lt. Rhula were heading toward the house of an imam, one of the village elders. Seconds later, an RPG streaked in from the east, followed by a burst from a PKM, the Russian-made machine gun that shoots a hefty 7.62-millimeter cartridge. It started tearing up the ground and the adobe walls. As the men took cover among the terrace walls, more PKM fire came from the northeast, joined by AKs at closer range.

Enemy fighters were crouched inside the houses and below the windows of the schoolhouse on the southern ridge. They were hiding in the alleyways and dug in behind the stone terrace walls to the east. They had a dozen fixed positions and were shooting downhill with the sun behind them.

* * *

I heard the shooting echoing through the valley, ragged at first and subsiding momentarily while magazines were reloaded. Then the volume increased, with mortar and RPG explosions mixed in. The advisor net crackled with voices stepping over each other. Fifteen Marines sharing one frequency were trying to radio their positions and the locations of the enemy.

Bedlam isn’t unusual in the first seconds of an attack. When dushmen open fire, they usually rip through several magazines while our guys go flat and scramble for position. Within minutes, the troops normally settle down, the senior man controls radio traffic, the forward observer calls in artillery and helicopters, and the enemy rate of fire slackens. The dushmen then scamper over the ridges and, ten minutes later, quiet descends.

Not this time. I waited for the firing to die down, but it didn’t. The staccato chaos of RPG explosions, PKM machine guns, AKs, and M16s increased. I heard the report of a recoilless rifle—basically, a 100-pound, shoulder- or tripod-mounted cannon and a sure sign of a planned ambush, as the dushmen don’t lug that over the hills for exercise. Then I heard the crump-crump of their mortar shells.

There was a wild babble of voices on the command radio—advisors yelling at each other to clear the net. No one was taking charge. There was no central command. I was pacing around, frustrated at being out of the fight and not being able to help.

Gunny Chad Lee Miller, approaching his observation position high on the north ridge, saw an enemy strongpoint on a plateau only three hundred meters to his east. The enemy soldiers were launching rounds from a mortar tube while others, inside a bunker there, were firing a DSHKA, a massive Russian antiaircraft gun that sounds like a jackhammer hitting a manhole cover.

Staff Sgt. Guillermo Valadez, another advisor, and six Askars were on a ledge about fifty meters below Miller. They also were facing east, looking directly at the same enemy. Soon both ridgelines were sparkling with fire, as the Askars and dushmen engaged each other with rocket-propelled grenades. Smoke and shrapnel filled the air.

Across the narrow valley on the south ridge, Capt. Ray Kaplan had trudged up to his observation position, winded by the steep climb and amazed by the stamina of Cpl. Steven Norman, a slight but tough Marine lugging a 240 machine gun and several belts of ammo.

Seconds after the ambush began, they were pinned down by PKM fire from the east. Cpl. Norman set up his gun and returned fire, killing the enemy gunner.

The first instinct of the Askars with Kaplan was to run downhill into the valley. Kaplan shouted them back into position.

It was a good thing, because a swarm of dushmen were maneuvering up the hill to overrun them.

Kaplan watched as one dushmen got to his feet to make a rush. Cpl. Norman stitched him squarely and he tumbled downhill. That knocked some enthusiasm out of the others. Kaplan seized the moment, ordering his Askars to spread out and find cover, facing northeast, the direction of the main ground assault. For the next hour, the Askars, Kaplan, and Cpl. Norman would duel with PKM and AK gunners.

Kaplan made his men shift their positions constantly so the dushmen couldn’t zero in. He carried Viper binoculars with a laser that measured the distance and azimuth to a target. Before he could get the reading to call in, a bullet smashed through the binoculars. He was all right, but he couldn’t call in help from the artillery with any precision.

Enemy fire from the east was swelling like a thunderstorm. RPGs and mortars shells were dropping in, with machine guns delivering accurate fires from the north and south ridgelines. Swenson, marooned out on the terraces below the village, ducked behind a stone wall. He had marked nine artillery registration points on his map; each consisted of a number preceded by the letters KE. It wasn’t Swenson’s job to act as the forward observer and to call in fire, but he responded automatically.

“This is Highlander 6!” he yelled over the din. “Forward line of troops pinned down at X-Ray Delta 96873 51568. Heavy enemy fire. Request immediate suppression. Fire Kilo Echo 3070. Will adjust.”

The southern ridgeline was so high that Swenson’s radio couldn’t reach the operations center at Joyce, only two miles away. Kaplan, recovering from a bullet into his binoculars, tried to relay the message from his higher perch, but portions of it were garbled. Higher up on the ridge, Staff Sgt. Thomas Summers of the Army scout-sniper team, Shadow 4, finally relayed the message to the TOC.

“Fire KE 3070,” Sgt. Summers said. “I will relay adjustments.”

I heard the radio command. KE 3070 was the “Undo” fire mission, signaling a withdrawal. Swenson hadn’t wasted any time. Once the smoke shells started landing, I assumed Team Monti would pull back. I knew what Rod and I had to do when that happened. That was obvious.

“What you think, man?” Rod said.

“If the dushmen cut around the rear,” I said, “and close the back door, they’ll catch our people in a fire sack. This is deep shit. They gotta get out of there.”

The way to break up an ambush is to hammer it with heavy fire. The Humvee gave us armor, mobility, and a heavy gun. We could roll in and bring Team Monti back to the location of the Command Group. I grabbed the radio and called Fox 3—Lt. Fabayo. No reply. I tried Fox 6—Williams—and then Fox 9—1st Sgt. Garza. No one replied. I was calling for permission to enter the valley, asking for it from anyone who would answer.

Finally, Fox 7—Valadez, up on the northern ridge—answered on the net.

“Fox 3-3, your requests to enter the valley are denied. Fox 9 says you are to stay at your present location.”

It made no sense. On my truck was mounted the Mark 19 belt-fed 40-millimeter grenade launcher. Fearsome. It spat out explosive shells as big as a man’s fist.

I put down the handset and sat there, listening as a dozen advisors tried to talk over a single radio channel. It was sheer bedlam.

Читать дальше