Japan, I think, became for Eduardo the continuation of America by other means, and the excitement of an endlessly self-renewing technology lay at the centre of the Japanese dream. He would return from Japan loaded with high-tech toys, bizarre robots equipped with electronic sensors that could lumberingly make their way around his studio. He once rang me from Tokyo, and I could barely hear him above a background babble of Japanese voices. He explained that he was near a bank of cigarette automats with voice-actuated brand selectors. He shouted above the din: ‘It’s midnight, there’s no one here. The machines break down and start each other talking…’ I wish Eduardo had pursued all this in his sculpture, and can still hear the robots jabbering in the darkness, with their ‘Please come again’ and ‘Thank you for your custom’ going on through the night.

Germany was another great magnet for him, and the country where his sculpture was most admired. I remember telling him that Chris Evans had found some wartime film cans stored in a basement at the National Physical Laboratory, among them a Waffen SS instructional film on how to build a pontoon bridge. Eduardo was deeply impressed. ‘That says it all,’ he murmured, his imagination stirred by the fusion of these almost emblematic elite troops with the down-to-earth realities of military engineering. I suspect his obsession with Wittgenstein, the Austrian-born philosopher and Cambridge friend of Bertrand Russell, had far less to do with The Tractatus than with Wittgenstein’s trips to the cinema to see Betty Grable.

Eduardo knew few novelists, if any, though the same could be said of myself. I felt far more at ease with a physician like Martin Bax, or with Chris Evans and Eduardo, than I did with my fellow novelists in the late 1960s. Most of them were still locked into a literary sensibility that would have been out of date in the 1920s. I’m glad to say that the novel has changed very much for the better in recent years, and a new generation of writers has emerged, among them Will Self, Martin Amis and Iain Sinclair, with powerful imaginations and a wide, roving intelligence.

The last literary party I attended, at my publishers Jonathan Cape in the early 1970s, at least brought me a little closer to the threatening Lord Goodman. I arrived with my agent, John Wolfers, a highly cultivated man who had served in the Welsh Guards and been wounded in the battle for Monte Cassino. He was also a compulsive drinker, locked into an intensely competitive relationship with the head of Cape, Tom Maschler, with whom he had been to school. The evening of the party John was deeply drunk, and barely able to stand upright. I tried to support him, but he pushed me away, talked incoherently for ten seconds and suddenly crashed to the floor, like a giant tree falling in a forest, taking two or three smaller guests with him. This happened several times, and was soon clearing the room.

Eventually I managed to steer him down the stairs. There were no taxis cruising Bedford Square, but a uniformed chauffeur stood by a double-parked limousine. Taking out a £5 note (then probably worth £50) I offered it to the chauffeur if he would take John home. ‘Regent Square, five minutes away.’ He accepted the fiver, and we laid John out in the rear seat. As the chauffeur started the engine I asked: ‘By the way, whose car is this?’ He replied: ‘Lord Goodman’s.’

I’m surprised I didn’t find myself in the Tower.

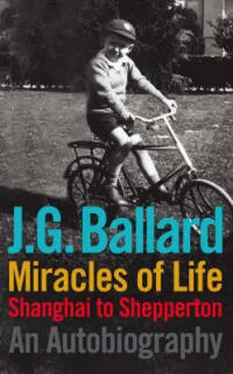

I still think that my children brought me up, perhaps as an incidental activity to rearing themselves. We emerged from their childhood together, they as happy and confident teenagers, and I into a kind of second adulthood enriched by the experience of watching them grow from infancy into fully formed human beings with minds and ambitions of their own. Few fathers observe this extraordinary process, the most significant in all nature, and sadly a great many mothers are so distracted by the effort of running a home and family that they are scarcely aware of the countless miracles of life that take place around them every day. I think of myself as extremely lucky. The years I spent as the parent of my young children were the richest and happiest I have ever known, and I am sure that my parents’ lives were arid by contrast. For them, domestic life was little more than a social annexe to the serious business of playing bridge and flirting at the Country Club.

My friendships with Eduardo Paolozzi, Dr Martin Bax, Chris Evans and Michael Moorcock were important to me but lay on the perimeter of my life, and anyway depended on reliable babysitters and the parking regulations of the day. My children were at the centre of my life, circled at a distance by my writing. I kept up a steady output of novels and short-story collections, largely because I spent most of my time at home. A short story, or a chapter of a novel, would be written in the time between ironing a school tie, serving up the sausage and mash, and watching Blue Peter . I am certain that my fiction is all the better for that. My greatest ally was the pram in the hall.

The 1960s were an exciting decade that I watched on television. Driving the children to and from school, to parties and friends, I had to be very careful how much I drank, regardless of the breathalyser. I was a passive smoker of a good deal of cannabis, and once took LSD, completely unaware of the strength of a single dose. This was a disastrous blunder that opened a vent of hell, and confirmed me as a long-standing whisky drinker.

Fay and Bea had taken charge of family life, and Jim and I were happy to follow orders. This was excellent training for all of us, especially the girls. They made the most of school and university, and have enjoyed successful careers in the arts and the BBC. They married happily and have families of their own. From the start I drummed into them that they were as entitled to opportunity and success as any man, and should never allow themselves to be patronised or exploited.

My daughter Fay Ballard .

As it happened, I could have saved my breath; they knew exactly what they wanted to do with their lives, and were determined to do it.

Some fathers make good mothers, and I hope I was one of them, though most of the women who know me would say that I made a very slatternly mother, notably unkeen on housework, unaware that homes need to be cleaned now and then, and too often to be found with a cigarette in one hand and a drink in the other – in short, the kind of mother, no doubt loving and easy-going, of whom the social services deeply disapprove. The women journalists who have interviewed me over the years always refer to the dust that their gimlet eyes detect in unfrequented corners of my house. I suspect that the sight of a man bringing up apparently happy children (to which they never refer) alerts a reflex of rather old-fashioned alarm. If women aren’t needed to do the dusting, what hope is there left? Perhaps, too, the compulsive cleaning of a family home is an attempt to erase those repressed emotions that threaten to break through into the daylight. The nuclear family, dominated by an overworked mother, is in many ways deeply unnatural, as is marriage itself, part of the huge price we pay to control the male sex.

The absence of a mother was a deep loss for my children, but at least my girls were spared the stress that I noticed between many mothers and their daughters as puberty approached. As a father who collected his children from school, I spent a great deal of time by the school gates, and soon recognised the fierce maternal tension that made adolescence a hell for many of my daughters’ friends. Some mothers simply could not cope with the growing evidence that their daughters were younger, more womanly and more sexually attractive than they were. Sex, I’m glad to say, never worried me; I was far more concerned about what might happen to my daughters in a car rather than in a bed. A few words of friendly advice and the address of the nearest family planning clinic were enough; nature and their innate good sense would do the rest.

Читать дальше