Chris’s death from cancer in 1979 was a tragic loss to his family and friends, all of whom have vivid memories of him.

In 1964 Michael Moorcock took over the editorship of the leading British science fiction magazine, New Worlds , determined to change it in every way he could. For years we had carried on noisy but friendly arguments about the right direction for science fiction to take. American and Russian astronauts were carrying out regular orbital flights in their spacecraft, and everyone assumed that NASA would land an American on the moon in 1969 and fulfil President Kennedy’s vow on coming to office. Communications satellites had transformed the media landscape of the planet, bringing the Vietnam War live into every living room.

Surprisingly, though, science fiction had failed to prosper. Most of the American magazines had closed, and the sales of New Worlds were a fraction of what they had been in the 1950s. I believed that science fiction had run its course, and would soon either die or mutate into outright fantasy. I flew the flag for what I termed ‘inner space’, in effect the psychological space apparent in surrealist painting, the short stories of Kafka, noir films at their most intense, and the strange, almost mentalised world of science labs and research institutes where Chris Evans had thrived, and which formed the setting for part of The Atrocity Exhibition .

Moorcock approved of my general aims, but wanted to go further. He knew that I responded strongly to 1960s London, its psychedelia, bizarre publishing ventures, the breaking-down of barriers by a new generation of artists and photographers, the use of fashion as a political weapon, the youth cults and drug culture. But I was 35 and bringing up three children in the suburbs. He knew that however much I enjoyed his parties, I had to drive home and pay the baby-sitter. He was ten years younger than me, the resident guru of Ladbroke Grove and an important figure and inspiration on the music scene. It was all this counter-cultural energy that he wanted to channel into New Worlds . He knew that an unrestricted diet of psychedelic illustrations and typography would soon become tiring, and responded to my suggestion that he dim the LSD strobe lights a little and think in terms of British artists such as Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi.

I still remembered the 1956 exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, This is Tomorrow, and I regularly visited the ICA in Dover Street. Many of its shows were put on by a small group of architects and artists, among them Hamilton and Paolozzi, who formed a kind of ideas laboratory, teasing out the visual connections between Egyptian architecture and modern refrigerator design, between Tintoretto ‘crane-shots’ and the swooping camera angles of Hollywood blockbusters.

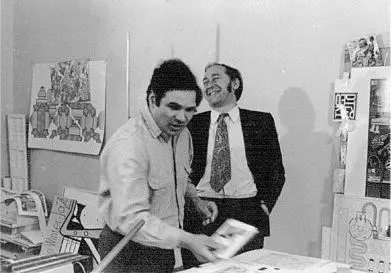

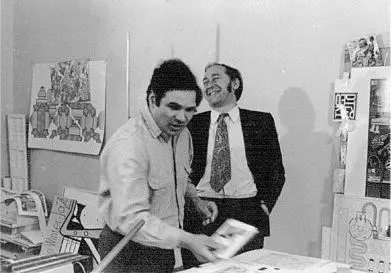

In Eduardo Paolozzi’s Chelsea studio, 1968 .

All this was closer to science fiction, in my eyes, than the tired images of spacecraft and planetary landscapes in s-f magazines.

I remembered that in the 1950s Paolozzi had remarked in an interview that the s-f magazines published in the suburbs of Los Angeles contained more genuine imagination than anything hung on the walls of the Royal Academy (still in its Munnings phase). With Moorcock’s approval, I contacted Paolozzi, whose studio was in Chelsea, and he invited us to visit him.

We got on famously from the start. In many ways Paolozzi was an intimidating figure, a thuggish man with a sculptor’s huge arms and hands, a strong voice and assertive manner. But his mind was light and flexible, he was a good listener and adept conversationalist with a keen and well-stocked mind. Original ideas tripped off his tongue, whatever the subject, and he was always pushing at the edges of some notion that intrigued him, exploring its possibilities before filing it away. A woman-friend I introduced to him exclaimed: ‘He’s a minotaur!’ but he was a minotaur who was a judo expert and light on his feet.

He and I became firm friends for the next thirty years, and I regularly visited his studio in Dovehouse Street. I think we felt at ease with each other because we were both, in our different ways, recent immigrants to England. Paolozzi’s Italian parents had settled in Edinburgh before the war, where they ran an ice cream business. After art school he left Scotland and attended the Slade in London, quickly established himself with his first one-man show, and then left for Paris for two years, meeting Giacometti, Tristan Tzara and the surrealists. He always insisted that he was a European and not a British artist. My impression is that as an art student he had felt deeply frustrated by the limitations of the London art establishment, though by the time I knew him he was well on the way to becoming one of the tallest pillars in that establishment.

Everyone who knew him will agree that Eduardo was a warm and generous personality, but at the same time remarkably quick to pick a quarrel. Perhaps this touchiness drew on the deep personal slights he suffered as an Italian boy in wartime Edinburgh, but he fell out with almost all his close friends, a trait he shared with Kingsley Amis. One of his disconcerting habits was to give his friends valuable presents of pieces of sculpture or sets of screen-prints and then, after some largely imagined slight, demand the presents back. He fell out spectacularly with the Smithsons, his close friends and collaborators on This is Tomorrow. After giving them one of his great Frog sculptures, he later informed them that he wanted it returned; when they refused, he went round to their house at night and tried to dig it out of their garden. Their friendship, needless to say, never recovered.

I have often wondered why Eduardo and I never fell out, though my partner Claire Walsh, who was present at the time, claims that we had our ‘break-up’ row on the second day we met. I think Eduardo realised that I was a genuine admirer of his work, and that apart from his lively imagination and powerful mind I wanted nothing from him. He was a generous and sociable man, and tended to attract an entourage of graduate students, museum curators, art school administrators eager for him to judge their diploma shows, well-to-do art lovers and ladies who lunch – in short, what used to be called sycophants. This became a real problem for him in the 1980s once he accepted his knighthood.

To what extent did Eduardo’s very busy social life influence his work, possibly for the worse? I greatly admire his early sculpture, those gaunt and eroded figures cast from machine parts who resemble the survivors of a nuclear war. It’s difficult to imagine the Paolozzi of the 1980s, who dined most evenings at the Caprice, a few steps from the Ritz, producing those haunted and traumatised images of mankind at its most desperate. By the end of the 1960s his sculpture had become smooth and streamlined, and resembled modules from some high-tech design office working on a new airport terminal.

I think he was aware of this, and sometimes he would say: ‘Right, Jim … let’s go out.’ And we would prowl the side streets off the King’s Road, where he would search the builders’ skips, his huge hands feeling some piece of discarded wood or metalwork, as if looking for a lost toy. Then it would be back to the Caprice, with its showbiz and film-star clientele, its dreadful acoustics and cries of ‘Eduardo…!’ and ‘Francis…!’ Why Bacon spent any time there is another mystery. Eventually, by the late 1980s, I had to retreat gently from this competitive circus.

But for the most part Eduardo enjoyed an idyllic life, and I watched him with real envy as he worked in his studio, listening to music while he cut up images for his screen-prints, chatting to an attractive graduate student, recounting another traveller’s tale about his latest trip to Japan, a country that fascinated him even more than the US. His early obsession with all things American rather faded after his teaching trip to Berkeley in the late 1960s. He told me how he had taken a party of his students on a field trip to a Douglas aircraft plant, but they had been bored by the whole venture. Advanced technology might spur the imagination of a European, but Americans took it for granted, and were no more inspired by the assembly of a four-engine jet plane than by the process of sealing beans into a can.

Читать дальше