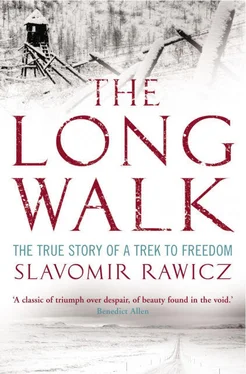

The President held up a document. A court official took it from him and brought it over to me. ‘Is that your signature?’ asked the President. I looked closely for a full minute while the court waited. It was my signature. Wavery and thin. But unmistakably my signature. Kharkov, I thought. That night at Kharkov.

‘Is that your signature?’ repeated the President.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘But I do not remember signing and it does not mean I admit anything contained in this document.’

‘That document,’ he continued, ‘is a full list of the charges against you.’

‘I know it well,’ I replied. ‘But no one would ever let me read it. I never knowingly signed it.’

‘It is your signature, nevertheless?’

‘It is my signature, but I cannot remember writing it.’

There were whispered consultations up and down the table. The President stood, the court stood. He read the charges at length. He announced that the court had found me guilty of espionage and plotting against the people of the U.S.S.R. It took quite a long time to get through all this and all I was waiting for was the sentence. It came at last.

‘You will therefore be sentenced to twenty-five years forced labour.’

‘And that,’ said the blue-uniformed major on the President’s right, ‘should be ample time to restore your shocking memory.’

I stood there for a moment looking down the table. I caught the eye of Mischa, the elegant, well-groomed Mischa. He was standing back slightly from the table. He smiled. There was no malice in that smile. It was friendly, the smile of a man who is stepping forward to shake your hand. It was almost as though he were encouraging me, complimenting me on the show I had put up. He was still smiling when one of the guards tugged at my blouse to turn me round. I passed through the curtain and was taken back to my cell.

Food was brought to me, a big meal by prison standards, and drink. The guards talked again. I felt a great weight had been lifted from me. I slept.

3. From Prison to Cattle Truck

THERE WAS evidence the next day that the prison authorities had taken immediate note of my change in status from having been a prisoner under interrogation and trial to that of prisoner under sentence. I was restored to full rations — coffee and 100 grammes of the usual black rye bread at 7 a.m. and, in the evening, another 100 grammes of bread and a bowl of soup. The soup was merely the water in which turnips had been boiled, without salt or any seasoning, but it was a welcome change of diet.

I was awarded, too, my first hot bath since my arrest. The wash-house to which I was escorted by my two guards was about twenty yards from my cell and differed from the others I had used only in having two taps in the wall instead of one. Off came my rubashka, I stepped out of my trousers and canvas shoes and stood in the shallow sink let into the stone floor. I turned on the right-hand tap and the hot water gushed out. There was no towel, no soap, but this was luxury. I jumped about, bent down against the tap and let the water run over me from head to foot, rubbed myself until my pale skin began to glow pink.

The two guards, one armed with a Nagan-type pistol in an unbuttoned holster, the other with a carbine, lounged one each side of the door watching my antics. Said one, ‘You will be all right now. You are going away from here.’ ‘When?’ I asked quickly. ‘Where to?’ Both guards ignored the questions. I carried on with my bath, making it last as long as I could. Then I turned off the tap and danced about to get dry. I dabbed at myself with my blouse and finally ran some water over my clothes and kneaded the prison dirt out of them until it flowed away in a dark stream down the hole in the sink. I rinsed them, wrung them, shook them and put them back on my body, the steam still rising from them. ‘You look a nice clean boy now,’ said the man with the carbine. ‘Let’s go.’

Back in my cell I was given a cigarette. One of the guards rolled the cigarette, lit it and then put it down on the floor. As he walked back I moved forward and picked it up. This was always the procedure when I was given a smoke. No guard would directly hand the cigarette to me, and if it went out before I took my first puff a single match would be thrown to me. The used match would be picked up and removed from the cell. Most of the many rigid security measures had obvious significance, but I could never quite appreciate the need for this elaborate care over a cigarette in the presence of two fully-armed men in the heart of a prison like the Lubyanka.

In spite of the fact that a prisoner was hopelessly equipped to attempt escape, the security drill was unvarying. A prisoner leaving or returning to his cell was always escorted by two guards. When a man was being taken out the guards took up position one at each side of the door. The prisoner would advance between them and halt a pace ahead of them. The instruction would then be given, to quote a typical example: ‘You will walk down this corridor on the left, turn right at the end and keep going until you are told to stop. Keep to the middle of the corridor all the way.’ These instructions were usually ended by the recital of an ominous little jingle which went:

‘Step to the Right,

Step to the Left —

Attempt to Escape.’

I must have heard that warning hundreds of times during my captivity. All guards used it, all prisoners knew it. The Russians took great pains to explain to a prisoner exactly where he was to go and the prisoner was left in no doubt that a deviation off course to right or left would mean death from the carbine or pistol of the guards marching two paces behind him. In the Lubyanka it seemed to be an excessive and almost ridiculous precaution, but later, when thousands of captives were being moved from one end of Russia to the other and escape became at least a possibility, the warning sounded sensible enough from the Russian point of view.

On the morning of the fourth day after my sentence an N.K.V.D. lieutenant entered my cell. ‘Can you read Russian?’ he asked. ‘Yes,’ I answered. He handed me a document which I found was a movement permit. Even convicted men apparently needed a permit to change their place of residence, although it might be a move only from prison to prison. The officer handed me a pen and I signed my name on the paper. He pocketed the permit and left.

Towards dusk on this mid-November afternoon in 1940 I quit my Lubyanka cell for the last time. I was marched out into the prison yard. Snow was drifting down and the cold had an edge which made me draw in my breath. Around the yard were a number of small buildings. At one end were the massive main gates, near which were two red brick storehouses. I was led to one of these and handed a brown paper parcel. The man who gave it me said, ‘This is for your journey,’ and smiled.

As I stood in the yard, one hand holding on to my trousers, the other gripping my parcel, I felt myself shivering with cold and with excitement. There was a great sense of freedom. I told myself, ‘Slav, my friend, this is goodbye to prisons. Wherever they take you, it won’t be to another stinking prison.’ I felt faintly elated. Whatever was ahead of me, here I was already breathing in good, clean, cold air and knowing I was going somewhere — not from cell to cell, from prison to prison, from one interrogator to another, but to a new life, a chance to work, to use my hands again, to meet and talk with other men…

Those other men, my fellow prisoners, were even now being escorted in small batches into the yard. I could feel my heart thumping as I watched each one of them arrive. I stared and stared. They eyed me and one another in the same way. We were all looking for someone we knew. But the odd thing borne in on me was that recognition was impossible. We were all in complete and uniform disguise. We were all longhaired and heavily bearded — I had not had a haircut or shave for nearly a year, but it had never occurred to me that all the others would have been treated alike. Our clothes were the same. When we had all been herded into the yard there were about 150 men like me all holding on to their trousers. One hundred and fifty lost souls turning up in the same pitiful costume at some devil’s fancy dress ball, each with a neat brown paper parcel in one hand and a pair of trousers in the other. The corners of my mouth twitched and I could almost have laughed, but suddenly I felt a choking wave of pity for us all that they should make such fools of us.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)