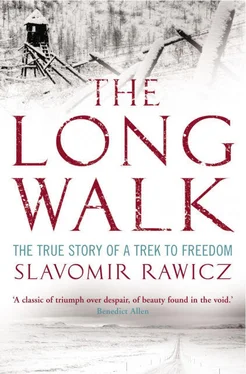

As the questioning really got under way I found myself grudgingly admiring the resolute singleness of purpose of the official Russian mind. All this I had gone through before in a series of appalling nightmares. Now, in the light of day, having emerged from the twisting, horror-filled corridors of frustration and despair, I found the dream persisting. Shortly stated, the indictment might have read: You, Slavomir Rawicz, being a well-educated middle-class Pole and an officer in the anti-Russian Polish Army, having a home near the Russian border, are therefore beyond any question of doubt a Polish spy and an enemy of the people of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. It remained only for the court to ask, with some asperity, why waste our time with denials?

After two hours the guards behind me were replaced. I found that the changing of the escort every two hours was the regular procedure throughout the trial. I went on answering the President’s questions. They afforded me no difficulty because they were the long, routine preliminaries. I had not yet reached the point where I had to think, to recognize a flash of danger and avoid some carefully-baited trap. Although it must have been clearly stated many times in the documents before him that I spoke fluent Russian, the President had meticulously repeated the question ‘Do you understand and speak Russian?’ Thereafter all the proceedings were in Russian and most of the questions were tinged with the special distrust which all Russians seem to have for the foreigner who knows their language. The underlying suspicion is that no foreigner would learn Russian if he did not want to be a spy.

As I stood there I was shaping my plans. I decided it would be to my advantage not to antagonize the court. I freely admitted those facts which were undeniable. Where an accusation was manifestly false I refuted it but asked the court’s permission to explain why it was so. They let me talk quite a lot. I agreed with this, partially acknowledged that, denied most things and almost eagerly did my explaining. The atmosphere was hostile but faintly interested in my methods. The rigid nature of the questions left me under no illusion that I could change the official attitude, but at least I felt I was not worsening my position by appearing anxious to co-operate with the court.

The informality of the proceedings impressed me. The members of the court smoked cigarettes endlessly. The stream of visitors I had noted while I was waiting for things to start continued while the hearing was on. There was a constant mutter of behind-the-scenes talking, little murmured exchanges with the men on the long table, smiles, hands laid on shoulders in a friendly and confidential way. As I listened and talked I observed all the new sights and sounds. Like a man at a theatre, I tried to assess the importance and significance of each character in order of appearance.

Most intriguing was a distinguished-looking man in uniform, tall, with white-streaked hair, who strolled through one of the curtained doors when the trial had been in progress about three hours. The President was half-way through a question when one of his flanking N.K.V.D. officers nudged him and inclined his head towards the door. The newcomer, his hand still holding the curtain, was looking round the court. His glance took me in, paused on my two guards and swung to the judicial bench. The President leapt to his feet. All the officials stood with great haste. There was a great scraping of heavy chairs. He had a nervous look, this distinguished visitor, a tense jerky gait as he walked over towards the beaming President. There were polite murmurs as he passed all the way down the table, of which I picked out repeatedly the greeting ‘Comrade Colonel’. The President shook hands warmly with Comrade Colonel and Comrade Colonel listened in a detached way to the President’s few remarks. Then he turned about, gave a smiling nod to the elegant Mischa and stood against the wall near the door through which he had arrived.

Comrade Colonel made some gesture and the court resumed its seat. The questioning was resumed. The visitor listened with apparent boredom, glanced up to the ceiling, appeared to be wrapped up in thoughts of things far more weighty than the trial of a mere Pole, and then, after about ten minutes slipped quietly out the way he had come.

About two o’clock in the afternoon the President yielded his place to a younger man and went off, presumably to lunch. There were changes among the officials in other parts of the long table. In this type of court it was apparently not necessary to preserve continuity. Anyone who had read the depositions could take over to give the principals a rest. The deputy-President had an air of efficiency which the older man lacked. His questioning was quicker, left less time to think. But he was not unpleasant, and soon after taking over he astonished me by offering me a cigarette. There was no catch. An official brought me a cigarette and lit it for me. I drew the smoke in and felt good. Before the end of the day they gave me another. Two cigarettes in a day. I felt that perhaps the signs were auspicious.

Comrade Colonel looked in once more during the afternoon, walked along the long table, picked up documents, laid them down, nervously exchanged words with two or three of the top men, and slipped out again. The examination went on.

The second change of guard at my back marked the passage of another two hours. Mischa now put in some rather leisurely cross-examination. Occasionally he smiled. I answered with a show of great willingness. I thought what a welcome change it was to be dealing with a man who seemed to have brought back with his stylish Western clothes some of the niceties of another civilization.

It almost seemed to me that there was even a remote touch of sympathy when they asked me about my wife. It was a brief enough story. I married Vera at Pinsk on 5 July 1939, during a forty-eight-hour leave from the Army. My mother called me from my place at the table during the wedding feast on the pretext I was wanted on the telephone. She handed me a telegram which ordered my immediate return to my unit. I packed my bags. Vera cried as I kissed her goodbye. The tears streamed down as she stroked my hair and face. So I went away, and most of the wedding guests did not know I had gone. A fortnight later I was able to get permission for her to come and stay near me at Ozharov. She stayed for four or five days and I was able to see her for about three hours a day. They were glorious, wonderful hours, in which we almost succeeded in banishing the sense of doom which hung heavily over us and over all Poland. It was all the married life I was to know with Vera. When I had fought the Germans in the West and the Russians had pushed in from the East I went back to Pinsk. The N.K.V.D. moved very swiftly. I had barely time to greet Vera, to answer her first eager questions, when they walked in. That was the last time I saw her.

About mid-afternoon when I had been standing before the court for well over four hours, the deputy-President asked me if I would like a cup of coffee. I said ‘Yes, please.’ That was when I was also given my second cigarette. The coffee was excellent — hot, strong and sweetened. When I had drunk and smoked — the coffee first and the cigarette afterwards because of my clumsy one-handedness — there were a few questions from a burly civilian at the opposite end of the table from Mischa. This man, I gathered, was my defence counsel. He showed every sign of irritation at the role he was forced to play and gave me the impression of being barely able to conceal his contempt for me. He took very little part in the trial and certainly his intervention at any stage did nothing to advance my cause. He was, at best, a most reluctant champion.

The day’s proceedings ended rather abruptly at about four o’clock. One of the two centre-of-the-table officers whispered to the deputy-President. An officer called my guards to attention and I was turned about and marched back to my cell. Food was brought me and I sat down to ponder the events of the day. I decided that my trial must be over, that there remained now only the formality of being told the sentence of the court. I did not think I had done badly this day. I even cherished a slight hope that the sentence would be light. That night I slept very well. It was the most restful night I had enjoyed for many months.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)