Lenin’s efforts to stake out a position to the left of most Zimmer wald partisans led to the formation of the Left Zimmerwald movement. As opposed to the Zimmerwald majority Lenin wanted no talk of peace as the overriding goal. Only socialist revolution could cut off the capitalist roots of war, and socialist revolution, in the short term, might require more fighting rather than less. Lenin also felt that the Zimmerwald majority was too easy on socialists who supported the war and too sentimental about the possibility of resurrecting the Second International. In private Lenin referred to the Zimmerwald majority as ‘Kautskyite shit-heads’. 13Left Zimmerwald was a minority within a minority but Lenin was unfazed. He was confident that the workers would soon support his stand, no matter how grim things looked at present. In a letter of 1915 Lenin calculated the forces he could count on during the upcoming Zimmerwald conference: ‘The Dutch plus ourselves plus the Left Germans plus zero – but that does not matter, it will not be zero afterwards, but everybody .’ 14

In early 1916 Lenin and Krupskaya visited Zurich so that Lenin could use the city library to research his book Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (another work that to a large extent is a defence of Kautsky-then against the apostasy of Kautsky-now). The visit kept being prolonged until the couple decided to stay permanently in Zurich. Here they lived, as Krupskaya recalled, ‘a quiet jog-trot life’, renting rooms in a shoemaker’s flat, attending performances by Russian theatrical companies and picking mushrooms (‘Vladimir Ilich suddenly caught sight of some edible mushrooms, and although it was raining, he began to pick them eagerly, as if they were so many Left Zimmerwaldians he were enlisting to our side’). 15Nevertheless, the role of one crying in the wilderness imposed a tremendous strain. Zinoviev recalled in 1918 that many who knew Lenin were surprised how much his appearance had altered under the stress of the war and the collapse of the International. 16

Despite his engagement with the Left Zimmerwald movement, Lenin did not give up hopes for ‘the commencing revolution in Russia’, only he saw it more than ever as part of a global revolutionary process. As he wrote in October 1915, ‘The task of the proletariat in Russia is to carry out the bourgeois democratic revolution in Russia to the end [ do kontsa ], in order to ignite the socialist revolution in Europe’ [Lenin’s emphasis]… There is no doubt that a victory of the proletariat in Russia would create extraordinary favourable conditions for the development of revolution both in Asia and in Europe. Even 1905 proved that.’ 17

There is a widespread impression that Lenin was growing downhearted and pessimistic about the chance of revolution just weeks before the fall of the tsar in early 1917. 18In actuality the approach of the Russian revolution during the winter of 1916–17 was visible even to Lenin and his entourage, observing events in far-off Switzerland. In December 1916 Lenin pointed to ‘the mounting mass resentment and the strikes and demonstrations that are forcing the Russian bourgeoisie frankly to admit that the revolution is on the march’. 19In a letter of 10 February 1917 to Inessa Armand Lenin related that his sources in Moscow were optimistic about the revolutionary mood of the workers: ‘there will surely be a holiday on our street’ (a Russian idiom meaning ‘our day will come’). 20

At the end of January 1917 – a few weeks before the February revolution was sparked off by street demonstrations in Petrograd – Lenin’s close comrade, Grigory Zinoviev, also observed that ‘the revolution is maturing in Russia’. Zinoviev also saw the approaching revolution in Russia through the lens of Lenin’s heroic scenario of class leadership. Zinoviev accurately conveyed – though perhaps in more flowery language than Lenin – the emotional fervour behind the Bolshevik scenario:

Oh, if one word of truth – of truth about the war, of truth about the tsar, of truth about the selfish bourgeoisie – could finally reach the blocked Russian village, buried under mountains of snow! Oh, if this word of truth would then penetrate even to the depths of the Russian army that is made up, in its vast majority, of peasants! Then, the heroic working class of Russia, with the support of the poor members of the peasant class, would finally deliver our country from the shame of the monarchy and lead it with a sure hand towards an alliance with the socialist proletariat of the entire world. 21

On 15 March 1917 Lenin learned about the thrilling events in Petrograd (the more Russian-sounding name given to St Petersburg at the beginning of the war): the tsar had abdicated, a government based on Duma representatives had taken power, and workers and soldiers had immediately formed a soviet based on the 1905 model. All Lenin’s thoughts now turned to getting to Russia, and since the Allied governments, especially England, had not the slightest intention of helping an anti-war agitator agitate against the war, he accepted the offer of travelling to Russia by means of a sealed train through Germany (most other Russian Social Democrats in Switzerland soon followed by the same route).

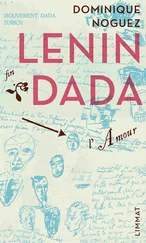

The train one which Lenin, Krupskaya, Inessa Armand and about thirty other émigrés travelled was sealed from Gottmadingen station on the German–Swiss border all the way to Sassnitz on Germany’s Baltic coast, where the travellers boarded a Swedish ferry. Lenin hoped that the strict rules forbidding contact between the Russian émigrés and any German citizens would minimize the impact of his ride through enemy territory. Although Lenin’s dramatic journey in the sealed train has attracted much attention, in essence it was no different from his train ride in 1914 from Krakow to Bern (true, the 1914 train was not sealed and Lenin was able to stop off in Vienna and thank Victor Adler in person). In each case the government of a country at war with Russia was glad to give safe passage to an enemy national who was a foe of the Russian government. We can also say about the 1917 train trip what we said about the 1914 trip: one man got on the train, another got off. In Switzerland Lenin was a marginal émigré, while in Petrograd he was a respected, even feared, party leader and a factor in national politics. The earlier train-ride from Krakow to Bern in 1914, however, did not mark a boundary in the evolution of Lenin’s views – Lenin still adhered to the same view of the world, only more so. In contrast, literally the day before his train left the Zurich station in 1917, Lenin’s scenario of class leadership underwent a modification with far-reaching implications.

Lenin photographed by a journalist while in Stockholm en route to Russia, April 1917. Lenin has yet to adopt the worker’s cap he wore following his return to Russia.

The so-called ‘April Theses’ announced by Lenin as soon as he arrived in Petrograd have traditionally been regarded as the expression of a major shift in Lenin’s outlook, yet identifying exactly what is new in these theses is quite difficult. The key parts of the April Theses – militant opposition to a government of ‘revolutionary chauvinists’ intent on continuing the war, all power to the soviets, winning over the peasants by advocating immediate land seizures and diplomacy bent on changing the imperialist war into a civil war – can all be found in a set of theses published in October 1915. Indeed the April Theses might very well be called the October Theses. 22

Читать дальше