And when Lenin realized that Solomon thought that having no Social Democratic presence in the Duma was preferable to the current situation, he indignantly interrupted: ‘What?! According to you, it’s better to let the Duma go on without any of our representatives at all?! Well, only political cretins and brainless idiots, out-and-out reactionaries, could think like that.’

At this point Solomon protested against what he considered personal attacks. Lenin backtracked, gave him a sort of hug, and assured him that the expressions that escaped him in the heat of argument were not meant to be taken personally – and perhaps they weren’t! (Similar apologies can be found throughout Lenin’s correspondence.) Lenin’s curiously impersonal abuse was not directed at Solomon as an individual, but against all the sceptics, pessimists, defeatists – in a word, philistines – who refused to lift themselves up to the grand vistas of his heroic scenario.

The ‘Commencing Revolution’

The differences among the Social Democrats were so sharp that the question more and more became: two parties or one? That is, were the various tactical and organizational differences among Social Democrats so great as to force a split? Many of the praktiki and the rank-and-file party members in Russia thought not, thus putting heavy pressure on the émigrés to work out a modus vivendi. But the upshot was that the party’s orientation veered back and forth as one or another faction gained control or, just as bad, the central institutions got bogged down into an enforced immobilisme . At one point in the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer a demon goddess and a normal human are forced to share the same body, each taking over at unexpected moments, each destroying the continuity of the other one’s life, each finding themselves in unexpected and embarrassing circumstances. The Russian Social Democratic party faced a similar situation.

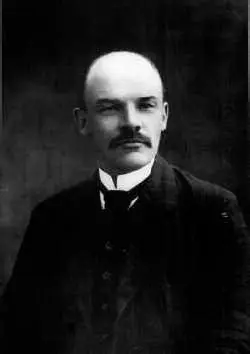

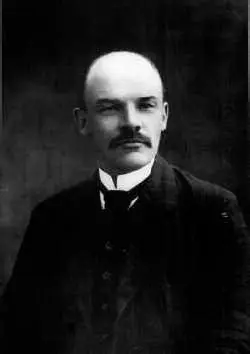

A formal portrait of Lenin in 1910, when he was living in Paris. Here he presents a respectable middle-class front, very unlike his image after the Revolution.

Lenin’s stand can be guessed from the title of a book he had Kamenev write in 1911: Two Parties . 34The argument of this book was that two parties existed de facto, and productive work would be impossible until they had a separate existence de jure. Lenin wanted to purify the party by pushing the Menshevik ‘liquidators’ out of the party and, to prove his bona fides, he did his best to push the Bolshevik ‘recallists’ out in the same way. Following a familiar logic the ‘conciliators’ within the party, the ones who wanted everybody to get along and therefore condemned any split, were also condemned.

Lenin and Grigory Zinoviev hiking near Zakopane, Poland, in the summer of 1913.

By 1912 Lenin had decided to cut the knot of Damocles by simply deciding that his group was the real party. After a series of institutional manoeuvres the so-called Prague Conference of January 1912 – consisting of Lenin, Zinoviev and about fourteen Bolshevik praktiki from Russia – elected a new Central Committee and thus a new party. Shortly after the Prague Conference Lenin and Krupskaya, accompanied by Zinoviev and his family, moved from Paris to Krakow in the Austrian section of Poland. Krakow was closer to Russia than any of Lenin’s previous exile locations and communication with Petersburg was relatively easy. The Bolshevik leadership nucleus considered this only a semi-exile.

Lenin’s change of residence coincided with a new mood in Russia – an upsurge of disaffection and militancy. The shooting down of striking workers in the gold-mines of Lena in Siberia was the mini-Bloody Sunday that crystallized the growing impatience. The Lena massacre on 17 April 1912 outraged all of Russian society; in particular, it sparked off a round of worker protests and strikes. The new worker militancy meant increased support for the Bolsheviks in the factional struggle and Lenin could now claim solid majority support in aboveground organizations such as trade unions and cooperative societies. The new Bolshevik aboveground presence was symbolized by the launch of a legal newspaper that later became world famous. The first issue of Pravda came out on 5 May 1912.

Lenin ended the second decade of his political career in much the same sort of situation as he began it, dangerously isolated in the world of international socialism but enjoying a solid base of support within the party back in Russia. The other émigré leaders of Russian Social Democracy did not agree on much, but they were all genuinely repulsed by what they saw as Lenin’s hard-line approach and arrogant splitting tactics. Just a little while earlier, Plekhanov had been a de facto ally of Lenin in the fight against ‘liquidationism’. But now even Plekhanov denounced Lenin’s unilateral election of a new Central Committee as an attempt to use for factional advantage party funds he had acquired by various crooked methods (arguments over party funds and Lenin’s methods in obtaining control over them had been going on for years). The exasperation of Russian party leaders with Lenin communicated itself to Western European socialists who felt called upon to try and make peace among the squabbling Russians. In July 1914 European socialist leaders met in Brussels in order to sort out these problems. Lenin’s representative, Inessa Armand, took an uncompromising stand, and probably only the outbreak of war later that summer saved Lenin from condemnation and complete isolation.

In contrast the Bolsheviks back home in Russia were gaining influence, giving Lenin a solid base to support his intransigence. Lenin constantly quoted statistics based on newspaper circulation and worker donations to back up his claim that the Bolsheviks were now the real representatives of the Russian worker movement. His typical optimism about the trend of events found expression in the instructions he sent Inessa Armand on how to present the Bolshevik case at the Brussels conference. If someone objected that the Bolsheviks had only a small majority within a certain section of the Russian party, he told her, she should answer ‘yes, it is small. If you like to wait, it will soon be écrasante ’. 35

Roman Malinovsky, Bolshevik Central Committee member and police spy.

The short slice of time between the Prague Conference of January 1912 and the outbreak of world war in August 1914 presents us with two of the greatest personal mysteries of Lenin’s career: Roman Malinovsky and Inessa Armand. Knowledge of Lenin’s heroic scenario allows us to shed at least some light on these mysteries. My discussion is limited to this aspect.

Malinovsky was a genuine man of the people who became prominent in the union movement after 1905 and was wooed by both Social Democratic factions as a candidate for the Fourth Duma that was elected in 1912. He joined up with the Bolsheviks and promptly became a real star. His eloquent speeches in the Duma effectively used the parliamentary tribune that was one of the very few legal channels for agitation open to the Social Democrats. But in actuality Malinovsky was on the payroll of the tsarist political police. Most people correctly deduced that he was an informer when in 1914 he suddenly and without explanation resigned from the Duma and fled the country. But Lenin doggedly defended Malinovsky’s innocence and viciously attacked anyone who suggested otherwise. Only after the fall of tsarism in 1917 was he forced to face the truth.

Читать дальше