Lars Lih - Lenin

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Lars Lih - Lenin» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Reaktion Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lenin

- Автор:

- Издательство:Reaktion Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781780230030

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lenin: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lenin»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Lenin — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lenin», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But Lenin’s plan hit a completely unexpected snag at the very moment of its fulfilment. The Iskra editorial board fell apart in ugly mutual recriminations. The divisive issues were dense and tangled, combining personal animosities, organizational jockeying for position and genuine difference in revolutionary tactics. These deeper differences only gradually rose to the surface, and resulted in the split between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks that dominated Social Democratic politics for the next decade. At the Second Congress in August 1903 Lenin had been the dominant party leader. But by the end of the year he was completely isolated – forced to leave the Iskra editorial board and on very bad terms with all his former colleagues (see chapter Three). For a while it looked like Lenin’s first decade as a party leader might be his last.

According to the banner sentence of 1894 the opening act of Lenin’s world-historical drama would see the Russian ‘purposive worker’ imbued with the ‘idea of the historical role of the Russian worker’, namely, to act as leader of the narod . Furthermore, ‘durable organisations [would be] created among the workers that transform the present uncoordinated economic war of the workers into a purposive class struggle’. Something like this actually happened. The Russian version of Kautsky’s canonical merger of socialism and the worker movement was the konspiratsiia underground, that unique and underappreciated historical creation of a whole generation of praktiki . Lenin’s individual role in this creation was, first, his summation of the logic of the threads strategy; second, his eloquent defence of the optimistic assumptions needed to sustain faith in the viability of a truly Social Democratic underground; and third, his ingenious plan for creating national party structures. As always a cold-eyed look at reality will reveal the yawning gap between the actual konspiratsiia underground and its heroic self-inscription into the narrative of Lenin’s banner sentence. Certainly for Lenin himself his first decade ended in bitterness and seeming isolation. Yet his dream, far-fetched as it may have been, was a historical reality because people believed in it.

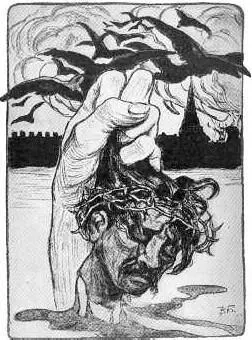

In a climactic passage from What Is to Be Done? Lenin evoked his heroic ‘other way’ as he outlined his ambitious project of using the newfangled methods of European Social Democracy in order to realize the dreams of Russian revolutionaries such as his brother Alexander. Lenin uses Alexander Zheliabov, a leader of the Narodnaya volya group that assassinated the tsar in 1881, to symbolize the Russian revolutionary tradition; he uses August Bebel, a worker who became the top leader of the German SPD, to sym bolize Social Democracy:

If we genuinely succeed in getting all or a significant majority of local committees, local groups and circles actively to take up the common work, we would in short order be able to have a weekly newspaper, regularly distributed in tens of thousands of copies throughout Russia. This newspaper would be a small part of a huge bellows that blows up each flame of class struggle and popular indignation into a common fire. Around this task – in and of itself a very small and even innocent one but one that is a regular and, in the full meaning of the word, a common task – an army of experienced fighters would systematically be recruited and trained. Among the ladders and scaffolding of this common organizational construction would soon rise up Social Democratic Zheliabovs from among our revolutionaries, Russian Bebels from our workers, who would be pushed forward and then take their place at the head of a mobilized army and would raise up the whole narod to settle accounts with the shame and curse of Russia.

That is what we must dream about! 36

3. A People’s Revolution

‘During the whirlwind [of the 1905 revolution], the proletarian, the railwayman, the peasant, the mutinous soldier, have driven all Russia forward with the speed of a locomotive.’

Lenin, 1906Bolshevism, as a distinct current in Russian Social Democracy, arose in the years 1904–14. During those years Bolshevism was a Russian answer to Russian problems. Later, when Bolshevism acquired a wider meaning, Lenin coined the term ‘Old Bolshevism’ as a label for the earlier period. ‘Old Bolshevism’ is a useful term that we will employ in later chapters. But for now Old Bolshevism is the only Bolshevism there is, so we shall dispense with the qualifying adjective.

In Lenin’s banner sentence of 1894 the crucial central episode of the heroic scenario is described in the following words: ‘the Russian WORKER, elevated to the head of all democratic elements, will overthrow absolutism’. These few words contain the essence of Bolshevism during its first decade, and we shall spend this chapter unpacking their meaning. We must first ask: what is the role of this episode in the overall heroic scenario? The answer: to open up the road to socialist revolution by removing the obstacle of tsarist absolutism. The more thoroughly the revolution did its job, the swifter would be the journey to the final goal. Therefore, the party’s goal should be revolution ‘to the end’ ( do kontsa ), that is, ‘to the absolute destruction of monarchical despotism’ and its replacement by a democratic republic. 1

According to the logic of Lenin’s heroic scenario, the only way to successfully carry out the democratic revolution ‘to the end’ is for the urban proletariat to be the head, the leader, the vozhd of all the ‘democratic elements’, that is, all the social groups with a stake in attaining full political freedom. The Russian revolution could only succeed as a narodnaia revoliutsiia , a people’s revolution. In order for the proletariat to play its destined leadership role it had to spread its message far and wide. And the only way to do that was through the institutions of the konspiratsiia underground. The Russian revolution could only succeed if these channels were kept open.

During the years 1905–7 Russia underwent a profound revolution and the tsar was forced to grant a significant measure of political freedom. When Lenin viewed these events through the lens of his heroic scenario he arrived at the following conclusions: The 1905 revolution was a vast, mighty people’s revolution. Unfortunately, the revolution was not able to go all the way ‘to the end’ by replacing tsarism with a democratic republic. It nevertheless achieved great things and represented a tremendous vindication of Social Democratic expectations. The decade-long consciousness-raising activity of the underground party paid off because the proletariat did indeed act as leader of the narod .

Lenin’s advice for the future was based on this reading of the events of 1905. The Russian Social Democrats needed to prepare for a decisive repetition of the 1905 revolution – one which would carry out the revolution to the end by creating a provisional government based on the workers and peasants. Only a government based on these classes (‘revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the workers and peasants’) would be able to install a democratic republic and beat back the counterrevolution with the necessary ruthlessness. The best way to prepare for this second people’s revolution was to remain loyal to the strategy that made the first one possible: the leadership role of the urban workers (‘hegemony of the proletariat’) and an energetic commitment to spread the socialist good news despite government repression.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lenin»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lenin» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lenin» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.