Harrison let me take the controls for a few minutes as we flew past the ventilator shafts for the Holland Tunnel. I held altitude and airspeed okay. I was working on feeling the aircraft, but I was pushing too much right rudder and the ship was out of trim. “Left rudder. Left rudder,” Harrison said.

“Yeah, I’m a little rusty, eh?”

“Yeah,” said Han Solo, Decker, and Indiana Jones, disappointed.

Later, after we pulled his chopper inside the hangar with the tug, I asked Harrison why he had read my book. “Everywhere I go, if it has anything to do with helicopters, people tell me I have to read Chickenhawk. So I did. And I agree.”

When he sat down at his desk to fill in his logbook, I noticed he had about five hundred hours in helicopters. He’s quite good for that amount of time.

Three months ago I had the chance to go visit my cockpit buddy, Jerry Towler. He lives close to Detroit, near one of our Vietnam pilot friends, Bob Baden. Bob had just restored a 1973 Bell-47G2 (the M *A *S *H helicopter, known as an H-13 in the Army). He’d let me rent it at cost, to see if I could still fly.

I rummaged around, found my army flight records, and checked the date of my last official flight. June 6, 1967! When I took the controls of Bob’s 47, I had not flown a chopper for almost thirty-seven years. What I wanted to do was attempt to get it up to a hover and not crash, unaided. Bob, who’s been flying all those thirty-seven years, agreed.

I’d never flown an H-13, the army’s designation of the Bell 47, when I was in the army. I knew it was a good machine.

I gradually got the machine light on the skids, feeling it beginning to shift a little, twitch like it was alive. Instincts took over. We lifted off the tarmac, the little Bell sounding far louder than the much larger Huey. Turbine engines are beautifully quiet in comparison to the 400 HP, six-cylinder, fuel-injected, snarling beast behind the cockpit seats.

It was thrilling to be drifting around just three feet off the ground. I wasn’t locked over a spot like I would’ve been thirty-seven years before, but I wasn’t dangerous, either. The chopper was noisy, it vibrated, and the throttle was sloppy—something Bob, who had worked as a helicopter mechanic and pilot for thirty years, advised me to notice. I was able to turn around, hover forward over the grass next to the runway. Mercifully, Bob operated the radios. I had my hands full keeping the machine within the confines of the taxiway. We were cleared with the local traffic for takeoff. I nosed the Bell forward, holding her close to the ground while she accelerated. We hit translational lift, surged up, free of gravity. You can call it translational lift, but that hardly describes how much fun it is.

Bob points beyond the plastic canopy. Don’t fly over those warehouses; avoid this neighborhood; break right here; give the highway plenty of clearance.

I’m looking for a place to land in case the engine suddenly takes a nap.

I was taught to fly as though the engine, brand-new or not, was preparing itself to enter motor oblivion precisely when you needed it alive and chugging. But there was nowhere to land below us except little tiny postage-stamp yards, wire-draped suburban streets, and a few swimming pools.

“Forced landings?”

“Anywhere you can fit it. Except roofs,” he said, nodding toward a vast complex of flat-roofed factory buildings.

“Why not?”

“Chances are you’d fall through the roof when you hit, probably kill some people working inside.”

“The highway?”

“Yeah, if you’ve got no other choice.”

I listened to the Lycoming grumbling. “She sounds great, though.”

Bob nodded, smiled.

I kept the airspeed somewhere between fifty and seventy, altitude around 500 feet as we fly toward the main airport. I was still grinning about how much pure fun this is! So what was nagging me? We flew across a crowded parking lot. Then I realized I’ve never flown over houses full of people before. That’s what was making me nervous? Houses? I flew combat assaults in jungles. Never neighborhoods. Flying over a perfectly normal American neighborhood, apparently with nobody shooting, made me wary.

Patience and I stayed with Jerry and Martie Towler while I went out to the airport every other day for flight instruction. And after a hiatus of thirty-seven years, everything I did was fresh and exhilarating. I still felt the thrill of practicing to control a machine that has been built to hover off the ground and not kill you. I was happy in the world of foot pedals, collective, throttle, cyclic. By my third hour with Bob, it was beginning to come back. We did autorotations: hovering, straight-ins, one-eighties, to make sure I’d at least be competent enough to survive a forced landing. If I had been grading me, I’d have given meaCride. I could do the maneuvers, but not with the smoothness of a practiced hand. But it was still fun. I would only get better each time I flew. Unfortunately, even at the reduced rate my friend Bob was letting me pay for the Bell, it’s obvious why it’s only military pilots and people like Harrison Ford who can fly helicopters around for the fun of it.

There’s got to be a way to make a more affordable hovering aircraft.

Patience is a publisher, writer, and editor. Her book Recovering from the War is still in print. She gives talks to veterans all over the country about post-traumatic stress disorder.

My son, Jack, is in school learning digital graphics. I have a grandson, also named Jack, who visits me on weekends, and who is the best grandson in the world.

My plans keep me busy. That frustrated engineer inside me is getting out more often. I’m writing, too. Upcoming is a book about the invention of vertical flight, a screen-play about Bill Reeder’s survival as a POW in Vietnam, a third Solo novel, and a movie I want to write and produce myself.

Where do I file for a life extension?

Robert Mason High Springs, Florida October 10, 2004

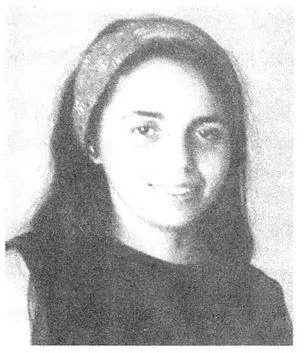

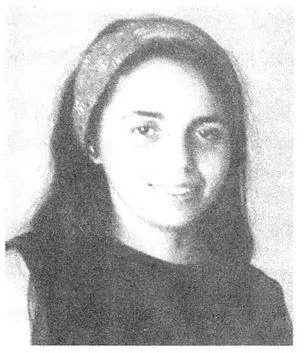

This is the picture of Patience I carried in Vietnam. She is twenty-two years old my true love, and the mother of our son, Jack.

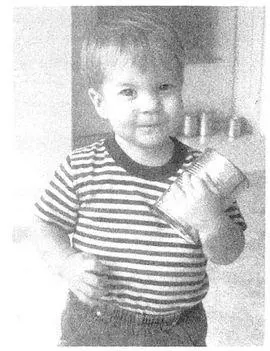

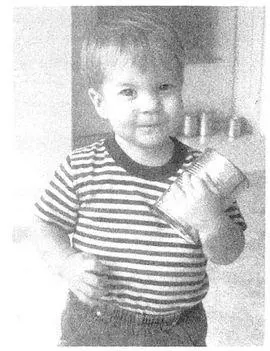

Jack is one and a half. He and Patience will wait for me in Naples, Florida.

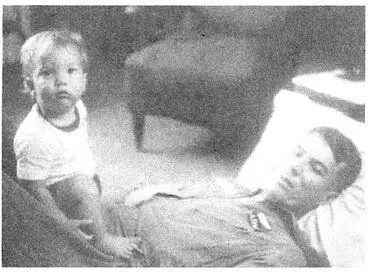

Catching a nap before a night training mission at Fort Benning. We’re forming up the First Air Cavalry, the world’s first combat airmobile division.

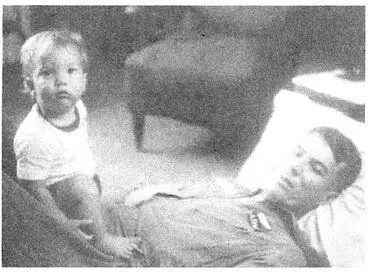

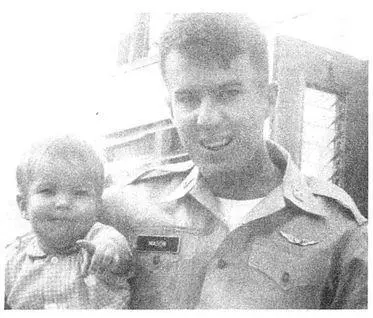

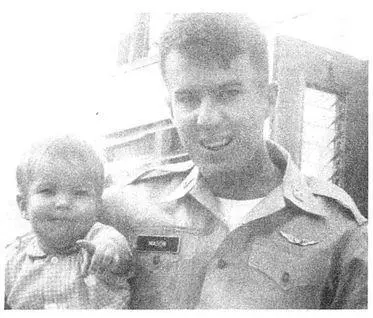

Patience takes a final snapshot of Jack and me. I’m on the way to join my battalion to board a ship for Vietnam.

On the deck of the USN Croatan , in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

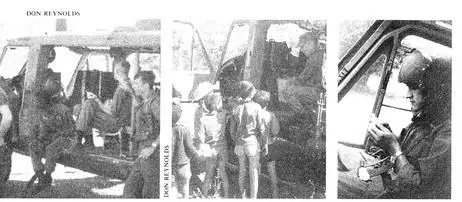

Gerald Towler (Resler), brand-new aviator like me, boarding the troop carrier Darby.

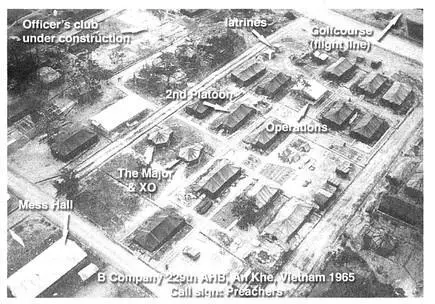

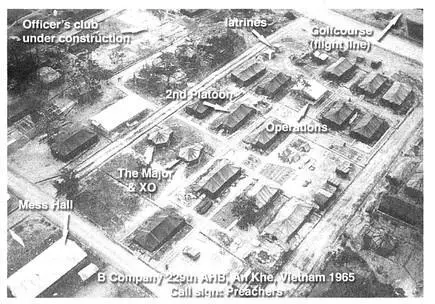

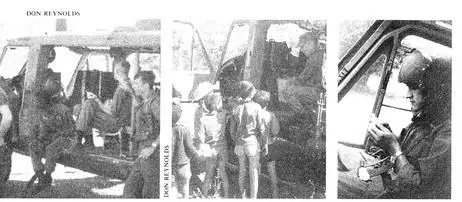

In An Khe, Vietnam, we set up a camp for us and our four hundred helicopters. By January 1966. this was the layout of B Company. 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion. I lived in the 2nd Platoon tent with these guys.

Clockwise in this group. Gerald Towler (Resler), Don Reynolds (Kaiser). Bob Kiess (Leese) and Dallas Harper (Banjo): Lee Komieh (Connors) and Watt Schramm.

Chuck Nay (Nate) at our posh bathing facilities.

Ken Dicus (Riker) in his cube in the 2nd Platoon tent.

From front to back, my platoon leader, Robert Stinnett (Shakcr). Captain Gillette (Gill), and Hugh Farmer practicing his golf swing.

Jack Armstrong and Tom Schaal (T. Shaw), from the 1st Platoon.

Preachers laager in a rice paddy.

Door-gunner Ubinski (Rubinski) during Happy Valley,

Crew chief Bill Weber (Red).

Crew chief Gene Burdick (Reacher) retrieved a Jeep driver’s foot, one of five soldiers we tried to rescue.

Howard Phillips (Morris) and Woody Woodruff (Decker) were always together.

A field briefing where I look for my lighter.

Low-level run up Happy Valley.

Dallas Harper, Neil Parker, and Lee Komich back from a mission,

Gasmasks were a bad idea.

Washing out the blood at the end of a busy day.

Extraction.

Door-gunners started out using bungic straps to hold their M-60 machine guns. Later, they were given mounts.

From inside the cockpit at a sandy LZ in Happy Valley.

Dropping troops off on a hilltop in Bong Son valley.

Kiess, Towler, and Mason in the cockpit.

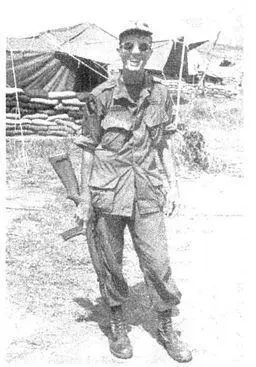

Looking happy with my new M-1 carbine.

Towler and I in our hex-tent at Dak To. We shared these quarters with Stoney Stizzle (Stoopy Stoddard).

Dawn preflight at Pleiku. I don’t think I was awake without a cigarette.

Lang, the cola girl.

Waiting to crank up at Dak To.

We spent a lot of time waiting between troop lifts and evacuations.

Towler in custody of the company’s mascot, Mo’fuck the Mongoose.

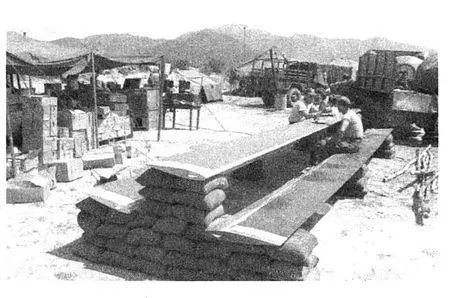

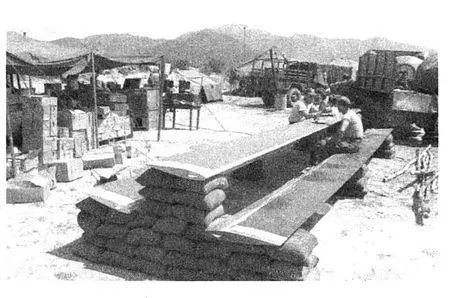

Kiess has coffee with a pilot on a picnic table made from ruined rotor blades, Happy Valley.

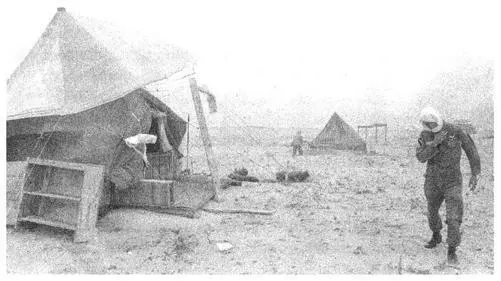

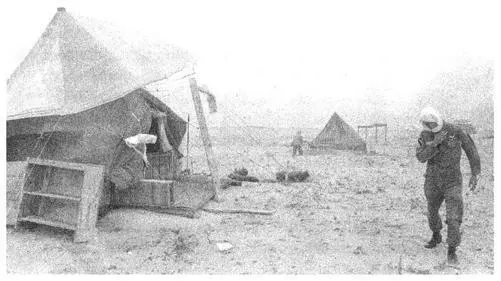

Towler battles a sandstorm on the beach at Tuy Hoa. That lone figure by the tent in the background is Stoney Stizzle who is heroically trying to anchor our tent.

Before I made the transition home, I made this swell ammo-box chair.

First day home. I’m at the kitchen table trying to look normal.

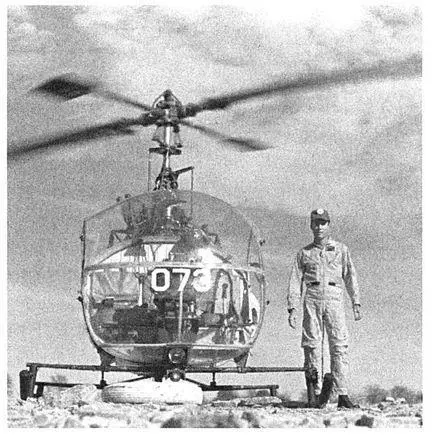

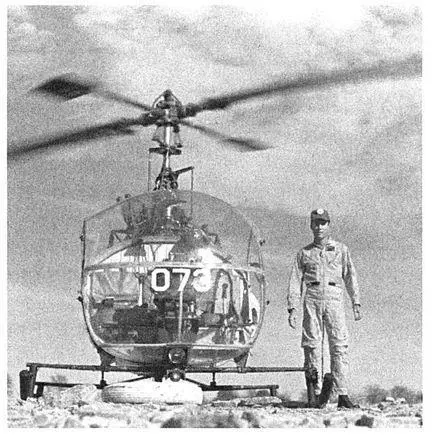

My new assignment was the flight school at Fort Wolters, Texas, where I became a flight instructor. The Hiller 23D is idling with the collective tied down while I inspect a practice LZ in the Texas brush.

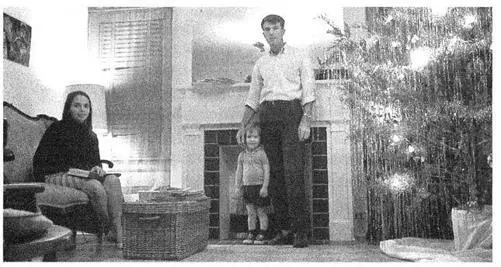

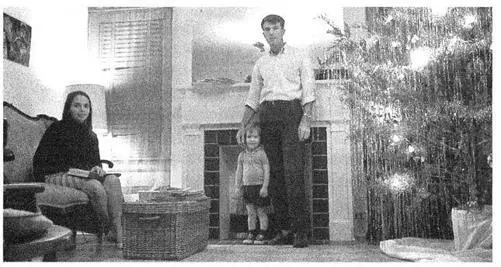

Our first family Christmas, Mineral Wells, Texas. Home at last.

FOR THE BEST IN PAPERBACKS, LOOK FOR THE

Читать дальше