I continued probing. “How long have you been in this service?”

“I just started doing this last Wednesday.”

“What kind of service is this?” Marek dared to ask.

“It was organized by Germans just recently, to guard all kinds of installations.”

“Including camps?” Marek continued.

“Yes. Mostly Jewish,” he disclosed. Then we knew that our guards were Poles. The pails were as full as we could get them, and we returned to camp.

Stasia waited for us at the open hearth. The peeled potatoes received a good washing, and we went back for more water. Tadek was anxious to be with his comrades, and he asked if we could find our way without him. “Yes!” we replied in chorus, eager to be alone. As we entered the forest, we realized that this was the first time we had been unguarded.

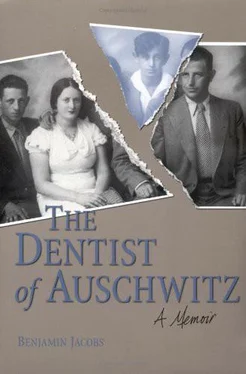

Marek Lewinski, I then learned, was an electrical engineer from Koo, a town less than fifty kilometers from Dobra. He was handsome, nearly two meters tall, and slender. He had an olive complexion, a straight forehead, and a slightly elongated nose. He had been seized in a Racia. The Nazis took no heed of his being the only male in the family. He and the other men of Koo were loaded on trucks and brought to join our transport. He never got to say good-bye to his wife and two children. The bitterness of his ordeal lay on his face. As he talked, his eyes glued to the ground, I sensed anger and condemnation of Koo’s Judenrat.

We were soon at the clearing. We put the pails on the slimy soil surrounding the water pit and sat down on a large rock. The peace and serenity we found in being alone brought a discharge of emotions. We were glad to have this opportunity to unburden ourselves of the rage accumulated in the last few days. Our new helplessness and despair, buried in our hearts for the last week, forced tears, and we both sat and cried.

About fifteen minutes later, at about a quarter to eight, we heard voices in the distance. As the sound grew, we heard young girls singing a gentle, popular Polish school graduation song. The singing dried our eyes, but suddenly the song stopped, and the cheer and beauty of it faded. As the silence persisted, that minute of softness seemed just a dream. I closed my eyes. It was difficult for me to let go. Suddenly I heard movement in the bushes, and raising my eyes, I saw another pair of eyes staring at me. The bushes soon parted, and before us, in the bright sunshine, five young girls emerged. We could not believe our eyes, but they were real.

“Dzie dobry” (Good morning). I greeted them quickly so they would not fear us.

“Dzie dobry,” they answered in unison. The five neatly dressed young girls with bundles under their arms radiated happiness. “Who are you?” they asked.

“We are Jews. My name is Bronek Jakubowicz. I am from Dobra. My friend Marek is from Koo.”

“What are you doing here?”

“We are at a camp called Steineck. Today is our first day at work at the Hoch und Tiefbaugesellschaft.”

“In Brodzice?” one of them asked.

“Yes.”

They were Jadzia, Halina, Kazia, Anka, and Zosia. Schoolmates before the war, they were all from Poznan, and they worked on a nearby plantation. Poznan, a city the Germans claimed, was the home of very few Jewish people. When the Nazis entered the city, it quickly became Judenfrei (free of Jews). When we told the girls about conditions in our ghettos, they were outraged. They were also shocked to learn about the conditions in camp. “All this just because you are Jews?” they asked. “Why? Why?” This was the question we never stopped asking ourselves. There was no end to their curiosity. They wanted to know why we were hairless. One stared at me, stretched her hand out, and said, “I am Zosia Zasina. I can’t believe the Germans can be so horrible.” What a lovely name, I thought. “You must be hungry. Here, take this,” she said, giving us her lunch.

It was embarrassing. I refused to accept. I wasn’t quite ready to forgo the normal gentlemanly response. “I can’t take it, Zosia,” I responded, her name rolling off my tongue softly.

“Please take it. Share it with your father,” she pressed. Hearing my father mentioned, I knew I should accept.

As if to comply with Zosia’s lead, the others left their food as well. “Please, please,” they pleaded, “give it to the others.” We thanked them warmly. “We’ll stop by tomorrow at the same time,” they said as they left. We watched as they disappeared into the thick forest with tears in their eyes.

Carrying the food bundles with us would give our secret away, so we buried them. Lest our guard come looking for us, we filled the pails and swiftly started back to the camp. I walked ahead on the narrow path. I was filled with excitement and longing for the next day. I saw Tadek coming toward us. I wasn’t sure how he would react if he found out about what had just happened. “We lost our way for a while,” I said. He accepted that, and we returned to a more impatient Stasia.

“Where have you been so long?” she queried.

“Oh, we strayed a bit, but we are sure of our way now,” I said, hoping we wouldn’t lose their trust and could continue bringing water by ourselves.

The guards, preferring to sit in the shade talking, smoking cigarettes, or playing cards, weren’t anxious to have to escort us. Stasia gave a short speech on how poorly the potato peelers did. She had to check each potato, to remove what she called eyes. I wanted to explain that until today they knew little about the art of potato peeling, but instead I just said, “In time you’ll see, they’ll do better.” For a moment it sounded like the old Nazi claim that Jews were lazy.

Returning again to the spring, I was still occupied with the thought of what had happened earlier. Zosia’s beautiful face pushed all others aside. I was moved by her generosity, kindness, and genuine concern. The food they left us was irresistible: tempting fresh bread, ham, kielbasa, cookies, and fruits. We ate more than our share there, and the rest we concealed in our pockets to take to the others. Stasia did not want any more water, so we waited for the midday break.

At noon work halted. As the foreman brought the inmates in front of the kitchen, out came the casseroles, pots, and saucepans. The foremen, supervisors, technicians, and engineers ate in the mess hall. Stasia prepared their food with particular reverence. She lunched with Mr. Witczak after everyone left. I saw that after just a half day of work my father looked worn. When I asked him whether the work was too difficult, he said, “No, I am strong. I can do it.”

Schmerele, an Austrian foreman in whose detachment Papa worked, quickly got a reputation for being a terrorizing bully. He demanded that every shovel be full each time it was lifted. At forty-seven, with a heart condition, my father wasn’t the person to lift fourteen-kilo shovelfuls of dirt all day. I gave Papa part of the things Marek and I had brought from the forest. I didn’t say where the food came from, and he didn’t ask.

The soup at Brodzice did not smell as foul as the camp slop. Although its main ingredients were potatoes and turnip, it contained slivers of horse meat. We scraped up every morsel. After the meal, Marek and I went back for more water. Our comrades headed back to work in the marshes. Witczak later ordered me to find out how many inmates each foreman had on each site, so only Marek was left to provide Stasia with dishwater.

Most earthmoving in those days, especially in Poland, was done with pick and shovel. As I proceeded through the site, I saw how hard our inmates worked digging and lifting the stringy soil, loading it on wheelbarrows, and pushing them hundreds of meters, for a new rail bed. Most of the foremen were more humane than Schmerele. As the inmates’ strength diminished, their attitude also changed. After I counted the inmates, I wanted to report to Witczak. His office curtains were drawn, so I knocked on the door. He opened it and took my notes without saying a word. I quickly learned that he wasn’t a man to waste words.

Читать дальше