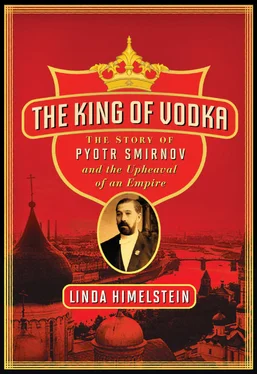

But those feelings were quietly set aside. More than anything, Smirnov was an opportunist and a capitalist. Liquor was what he knew—and he made the most of it. When Pyotr Smirnov died, he was the country’s leading producer of vodka, the chief of a business worth an estimated 20 million rubles (about $265 million today). 8He was one of the largest retailers of liquor in Russia—the purveyor to the tsar and Imperial Court—and his bottles were on the tables of royalty from Sweden to Spain. His personal fortune, including two immense homes, two vacation compounds, one factory and numerous shops, warehouses and cellars, topped 10 million rubles (roughly $132.7 million ), making him one of the wealthiest men in all of Russia. 9In 1886 he even captured one of the most elusive awards when he earned the title of hereditary honored citizen, an extraordinary accomplishment for an ex-serf and an honor that was bestowed on only the most deserving citizens.

It was an unexpected life, to be sure, built on sheer determination and an unwavering sense of purpose. Smirnov, a tall dashing man with a commanding presence, never had much use for the shades of gray that inhabited most people’s lives—tell him something couldn’t be done and he would do it twice just to make a point. It was a quality that brought out fear in some and great admiration in others. However it affected those around him, they knew they were in the presence of a man who would not be bound by normal constraints.

Perhaps that is why so many had turned out that bitter December day to stand in the cold and watch a funeral march by. The solemn, black-clothed crowd followed the slow procession, their footsteps crackling as they crunched through the freshly fallen snow. St. John the Baptist Church, one of Russia’s most ancient houses of worship, never looked more beautiful. Its three-tiered belfry, which towered above all else on this section of Pyatnitskaya Street, served as a beacon to Russians passing by that day. Tropical plants and brilliantly colored flowers framed both sides of the church; a walkway before the entrance was layered in black cloth. At the helm of the ceremony stood the highest ranked member of the Russian clergy, the Metropolitan Vladimir. He presided over official events for Russia’s tsars, and his presence alone left no doubt about the importance of Smirnov’s death.

Candles lit the way to the raised platform in the church where Smirnov’s body lay. A collection of sterling silver wreaths adorned the coffin. One wreath from his three older sons was inscribed: “To the unforgettable parent from his heartily loving children, Pyotr, Nikolay, and Vladimir Smirnov.” Another from Smirnov’s wife read: “To a dear, unforgettable husband from his loving wife.” 10Other wreaths from friends, workers, and admirers were piled onto the coffin as well.

The cold had crept into the church, but those who managed to make it through the doorway seemed not to notice. Heat coming from their bodies and breath offered enough warmth, especially as the voices in the choir began to rise. The liturgy lasted a full two hours, followed by an hour-long burial service.

The lengthy journey to Smirnov’s ultimate resting place began as his coffin was loaded onto a luxuriously adorned barrow. Three carts bursting with wreaths came next, followed immediately by the funeral chariot. Then, some one hundred carriages lined up to make the four-mile trip to the cemetery. The commoners would walk the route, which took them over the Cast Iron Bridge, past the Kremlin, and through Red Square. When they arrived at their destination, it was 3 PM. Daylight would last only another twenty-eight minutes.

Smirnov’s body was placed in the ground just before darkness fell and covered with stones and fresh dirt. A simple metal cross was erected, and then, it was over. Or was it? Smirnov was not a man to leave his final destiny to chance. He had requested in writing that prayers be said in at least forty churches for forty days after his death. His belief, which followed Russian Orthodox doctrines, was that it would take those forty days to determine whether his soul was bound for heaven or hell. He had instructed those around him to pray that his sins be forgiven and a place be made for him in paradise.

Was Smirnov afraid of what the afterlife might have in store for him? It’s not hard to imagine. More than a decade before Smirnov’s death, the stigma attached to alcohol—and alcoholism—was intensifying. The topic had been debated for many years. A handful of temperance societies had been founded. Writers had portrayed foul drunkards in their literature. They were always the lost, weak souls who could do little more than inspire pity and wreak havoc. Fyodor Dostoevskiy, for instance, whose own father was a cruel drunk, wrote passionately about the perils of alcoholism: “The consumption of alcoholic beverages brutalizes and makes a man savage, hardens him, distracts him from bright thoughts, blunts all good propaganda and above all else weakens the will, and in general uproots any kind of humanity.” 11These eloquent rants were certainly thought provoking, but they did not inspire a call to action, nor did they give anyone reason enough to take on a government addicted to its annual vodka windfalls.

At the height of Smirnov’s popularity in the 1880s, Russia’s anti-alcohol movement began a slow progression. More organizations touting sobriety popped up. More books described the harmful effects of alcohol. Writers, clergy, and doctors took up the cause. Apart from basic information on health, temperance leaders also had the sad state of the vodka industry on their side. At the time, hundreds of rogue distillers and corrupt tavern owners were operating throughout Russia. They cared little about the quality of their often dirty, bitter swill, which was routinely diluted with water, lime, or sandalwood. It had even been known to poison some unlucky imbibers.

All that mattered to these renegade producers was quantity. Their primary objective was to claim as many rubles as possible. They attacked one another, taking on leading producers of the day, such as Smirnov, Popov, and Shustov. They peddled counterfeit vodkas, including Smirnov’s, and some rivals even hired scientists to test vodkas made by the largest distillers—and then declared them rotten or impure.

The stoic Smirnov was incensed. He had spent his life cultivating an image of respect and morality that was beyond reproach. Smirnov fought back with full-page ads defending his vodkas and slamming his critics. He developed branded corks, hoping to trip up his rivals. The battles and Smirnov’s countermeasures riveted many observers, but to famed playwright Anton Chekhov, they were abhorrent—and examples of the worst of Russia. Long before he penned Uncle Vanya and The Cherry Orchard , Chekhov, a physician by training, chronicled in 1885 what he dubbed a “war” among vodka producers. He wrote about the peddlers of “satan’s blood,” the evil vodka makers who he predicted one day would destroy one another. In a column he wrote for Shards magazine in St. Petersburg, Chekhov singled out Smirnov as one of the chief offenders. “Each enemy, trying to prove that the vodka of his competitor is worthless, sends torpedoes, sinks ships, and exasperates with politics. What isn’t done in order to sprinkle pepper in the nose of the sleeping enemy?…In all likelihood, the war will end with the producers suing each other…. Fighting spiders eat each other so that in the end, only the legs are left.” 12

These public tongue-lashings pressured the tsar and his government, which finally determined that something needed to be done. In 1886, a law was passed making it a crime for employers to continue their common practice of substituting vodka or anything else for wages. All salaries were to be paid in cash. Pubs were banished. These laws, however, did little to sober up Russians—or the workplace. But they did embolden other anti-alcohol crusaders, the most celebrated one being Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy.

Читать дальше