The heavy wooden doors parted and the archdeacon from St. John the Baptist Church emerged, softly reciting prayers. A group carrying a coffin cover decorated with a wreath made of natural flowers fell into line after him. A choir came out then, singing the Holy God prayer, followed by a dozen workers. Each carried a pillow with sacred medals and honors earned by the deceased during an extraordinary life. Other church elders and dignitaries followed next, including ten priests wearing shimmering robes. At last, a coffin emerged, draped in a sumptuous fabric made of golden brocade and raspberry velvet.

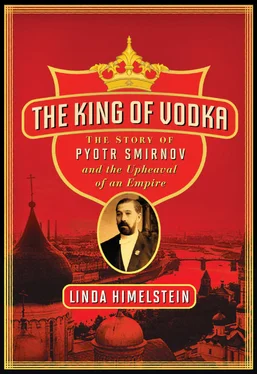

It was the second day of December, and this eloquent tribute was not for a tsar or a high-ranking minister or a military chief. The man inside the long oak box was Pyotr Arsenievich Smirnov, arguably the most famous vodka maker in the world.

That such a spectacle would be held for a man like Smirnov would have been unthinkable in 1831 when he was born at the family home in Kayurovo, a small farming village roughly 170 miles due north from Moscow. His parents were poor, barely literate, and most telling, they were serfs, part of Russia’s legally bound underclass. They were essentially slaves, owned by the proprietors of the land on which they lived and worked. All that they earned was shared with their landowners, who had control over what they did, where they went, and how they survived.

This commoner background, in tandem with Smirnov’s ultimate notoriety as a leading purveyor of liquors, was not a life that typically beat a path to prominence. Moreover, for the last decade of his life, alcoholism was raging throughout society and calls for increased controls on spirits producers were rampant. Still, when Smirnov died at age sixty-seven of heart failure, newspapers treated the event as a national tragedy. Descriptions like “distinguished,” “exemplary,” and “a giant of Russian industry” appeared in news stories. Smirnov’s passing shared the front page with the weightiest developments of the day—from the United States’s intention to sell the Philippines, to the controversial and scandalous Dreyfus Affair. Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery officer was serving time on Devil’s Island for allegedly passing military secrets to Germany. But supporters, including writer Émile Zola who published his renowned J’accuse letter, successfully proved that anti-Semites had framed Dreyfus. Ten months after Smirnov’s death, Dreyfus was pardoned, later becoming a knight in the French Legion of Honor.

From a certain perspective, Smirnov was a lot like Dreyfus. They were both underdogs, born into positions that were neither of their own making nor choosing. Dreyfus, a Jew; Smirnov, a serf—yet neither man let the disadvantage of their labels dictate their life choices. Smirnov had to overcome both his lowly status and a thoroughly unsophisticated, rudimentary makeup. Life in rural Russia was remote and plebeian, and as a serf Smirnov’s main occupations as a young boy likely would have been helping his mother care for younger siblings, lending a hand with the livestock and crops, and picking wild mushrooms and berries. He could not have attended school even if he had wanted to as none existed where he lived. When he did venture beyond his home village, the journey was fraught with peril—particularly at night. Smirnov would have had to carry metal sticks with him, banging them together or against trees to scare off hungry, wild wolves that lurked nearby. Young Pyotr was surely better off at home, tending to the family’s most immediate needs. [1] Little independent or primary evidence exists detailing Smirnov’s early childhood. This reconstruction is drawn from available data on serfs and information provided by Vladimir Grechukhin, the director of the Folk Ethnographic Museum in Myshkin, which houses a small museum devoted to Smirnov.

Young Smirnov, always obedient, did as he was told. But beneath his outwardly quiet and reserved demeanor, he must have been restless, internally agitated, a racehorse at the starting gate. It wasn’t as if he knew where he was going. Rather, he was someone who made where he was the very place to be. He devoured his surroundings, taking in seemingly inconsequential events and details and spitting them out as life-altering encounters. This was how he came to vodka.

IN RUSSIA, VODKA was as fundamental to daily life as food and the wintry chill. Around 1500, it is believed that monks were distilling the liquid in their monasteries, isolated hillside retreats where chemical experiments and scientific discoveries were routinely made. Surpluses of grain made production relatively easy—and cheap. Monks used primitive stills, producing liquor that often had a greenish blue tinge to it caused by traces of copper sulfate from the copper fermentation vessels—and a foul smell. 3In those days vodka wasn’t merely consumed for pleasure, it was a medicinal product. It could be a powerful disinfectant for wounds or a soothing, warm balm massaged into the back and chest. Its uses changed quickly, of course, becoming Russia’s beverage of choice when distilling methods were improved and medicinal additives were replaced with sweet aromas and tasty spices.

Almost overnight, vodka, whose name is derived from the Russian word voda , meaning water, became a focal point for a variety of rituals. A practice known as “wetting the bargain” used vodka as an inducement to bring communities together to build a church, bring in a harvest, or construct a bridge. A job well done meant that vodka would flow freely. Vodka drinking was also a favorite pastime of Peter the Great, who instituted the “penalty shot” during his reign from 1682 to 1725. It purportedly forced anyone late for a meeting or gathering to pay either a fine or drink a large cup of vodka. Over the years, vodka was used as payment in lieu of money, as a bribe, and as encouragement for soldiers on the front lines. The so-called drink of life was even fed to women in labor and to newborn babies when other remedies failed to calm them. The tsarist government, which maintained firm control over the vodka economy, sanctioned and encouraged these practices. Increased consumption of vodka was an easy way to pump up state coffers.

By the time Smirnov came around, vodka was an entrenched national habit. More than that it was big business, having surpassed salt to become the dominant source of revenue for the government. Taxes on vodka covered one-third of the state’s ordinary expenses and generated enough to pay for all of Russia’s peacetime defense. 4

Pyotr Smirnov saw how powerful vodka could be. His uncle Grigoriy operated hotels and pubs in Uglich, 5a town best known as the home base of Ivan the Terrible’s son in the sixteenth century. Grigoriy also ran a brewery and at least one wine cellar. 6As a young boy, Smirnov worked for his uncle. He washed dishes, mopped floors, waited tables, and tended bar. He must have observed how the men drank, how their teeth unclenched and their faces smoothed as soon as the drink passed their lips. He would have seen that the mere act of drinking, of swallowing, brought a pleasure rarely found within a Russian peasant’s arduous life. And he surely would have understood that vodka meant money—good money. The pubs, inns, and wine business had made Grigoriy, also a serf, wealthy enough to buy his freedom. He became a successful and admired businessman in his community, and young Smirnov yearned for that himself—and more.

In truth, Pyotr probably would have preferred a more outwardly honorable, less controversial vocation. He was a devout Orthodox Christian all his life, presumably attending confessions from the time he was seven. He was a collector of religious icons and a churchwarden of two Kremlin Court cathedrals, which were much-revered positions. 7As for liquor, he did not much care for it personally. He drank minimally, mainly to taste his own concoctions, join celebrations, or avoid insulting a thirsty guest. He rather despised the loud drunks who swallowed away what little money they had and made nuisances of themselves.

Читать дальше