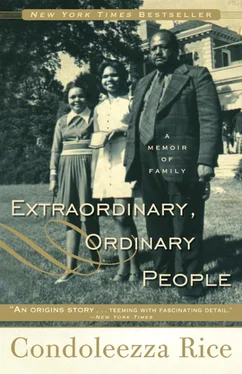

Condoleezza Rice

EXTRAORDINARY, ORDINARY PEOPLE

A Memoir of Family

To my parents,

John and Angelena Rice,

and my grandparents:

Mattie and Albert Ray,

and John and Theresa Rice

My parents, John and Angelena Rice, were extraordinary, ordinary people. They were middle-class folks who loved God, family, and their country. They loved each other unreservedly and built a world together that wove the fibers of our life—faith, family, community, and education—into a seamless tapestry of high expectations and unconditional love. I don’t think they ever read a book on parenting. They were just good at it—not perfect, but really good. Somehow they raised their little girl in Jim Crow Birmingham, Alabama, to believe that even if she couldn’t have a hamburger at the Woolworth’s lunch counter, she could be president of the United States.

As it became known that I was writing a book about my parents, I received many letters and emails from people who knew my mom and dad, telling me how my parents had touched their lives. In conducting this journey into the past I also had the pleasure of returning to the places my parents lived and talking with their friends, associates, and students. I am so glad I had the chance to connect with so many who knew them.

I was also contacted by people who didn’t know my parents but recognized in my story their own parents’ love and sacrifice. Good parents are a blessing. Mine were determined to give me a chance to live a unique and happy life. In that they succeeded, and that is why every night I begin my prayers saying, “Lord, I can never thank you enough for the parents you gave me.”

By all accounts, my parents approached the time of my birth with great anticipation. My father was certain that I’d be a boy and had worked out a deal with my mother: if the baby was a girl, she would name her, but a boy would be named John.

Mother started thinking about names for her daughter. She wanted a name that would be unique and musical. Looking to Italian musical terms for inspiration, she at first settled on Andantino. But realizing that it translated as “moving slowly,” she decided that she didn’t like the implications of that name. Allegro was worse because it translated as “fast,” and no mother in 1954 wanted her daughter to be thought of as “fast.” Finally she found the musical terms con dolce and con dolcezza , meaning “with sweetness.” Deciding that an English speaker would never recognize the hard c , saying “dolci” instead of “dolche,” my mother doctored the term. She settled on Condoleezza.

Meanwhile, my father prepared for John’s birth. He bought a football and several other pieces of sports equipment. John was going to be an all-American running back or perhaps a linebacker.

My mother thought she felt labor pains on Friday night, November 12, and was rushed to the doctor. Dr. Plump, the black pediatrician who delivered most of the black babies in town, explained that it was probably just anxiety. He decided nonetheless to put Mother in the hospital, where she could rest comfortably.

The public hospitals were completely segregated in Birmingham, with the Negro wards—no private rooms were available—in the basement. There wasn’t much effort to separate maternity cases from patients with any other kind of illness, and by all accounts the accommodations were pretty grim. As a result, mothers who could get in preferred to birth their babies at Holy Family, the Catholic hospital that segregated white and Negro patients but at least had something of a maternity floor and private rooms. Mother checked into Holy Family that night.

Nothing happened on Saturday or early Sunday morning. Dr. Plump told my father to go ahead and deliver his sermon at the eleven o’clock church service. “This baby isn’t going to be born for quite a while,” he said.

He was wrong. When my father came out of the pulpit at noon on November 14, his mother was waiting for him in the church office.

“Johnny, it’s a girl!”

Daddy was floored. “A girl?” he asked. “How could it be a girl?”

He rushed to the hospital to see the new baby. Daddy told me that the first time he saw me in the nursery, the other babies were just lying still, but I was trying to raise myself up. Now, I think it’s doubtful that an hours-old baby was strong enough to do this. But my father insisted this story was true. In any case, he said that his heart melted at the sight of his baby girl. From that day on he was a “feminist”—there was nothing that his little girl couldn’t do, including learning to love football.

My parents were anxious to give me a head start in life—perhaps a little too anxious. My first memory of confronting them and in a way declaring my independence was a conversation concerning their ill-conceived attempt to send me to first grade at the ripe age of three. My mother was teaching at Fairfield Industrial High School in Fairfield, Alabama, and the idea was to enroll me in the elementary school located on the same campus. I don’t know how they talked the principal into going along, but sure enough, on the first day of school in September 1958, my mother took me by the hand and walked me into Mrs. Jones’s classroom.

I was terrified of the other children and of Mrs. Jones, and I refused to stay. Each day we would repeat the scene, and each day my father would have to pick me up and take me to my grandmother’s house, where I would stay until the school day ended. Finally I told my mother that I didn’t want to go back because the teacher wore the same skirt every morning. I am sure this was not literally true. Perhaps I somehow already understood that my mother believed in good grooming and appropriate attire. Anyway, Mother and Daddy got the point and abandoned their attempt at really early childhood education.

I now think back on that time and laugh. John and Angelena were prepared to try just about anything—or to let me try just about anything—that could be called an educational opportunity. They were convinced that education was a kind of armor shielding me against everything—even the deep racism in Birmingham and across America.

They were bred to those views. They were both born in the South at the height of segregation and racial prejudice—Mother just outside of Birmingham, Alabama, in 1924 and Daddy in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1923. They were of the first generation of middle-class blacks to attend historically black colleges—institutions that previously had been for the children of the black elite. And like so many of their peers, they rigorously controlled their environment to preserve their dignity and their pride.

Objectively, white people had all the power and blacks had none. “The White Man,” as my parents called “them,” controlled politics and the economy. This depersonalized collective noun spoke to the fact that my parents and their friends had few interactions with whites that were truly personal. In his wonderful book Colored People , Harvard Professor Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr. recalled that his family and friends in West Virginia addressed white people by their professions—for example, “Mr. Policeman” or “Mr. Milkman.” Black folks in Birmingham didn’t even have that much contact. It was just “The White Man.”

Читать дальше