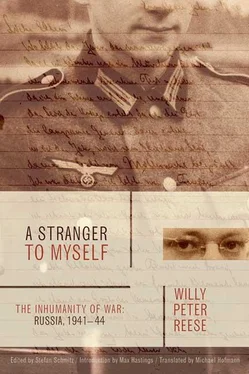

Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Stranger to Myself

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-42999-875-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Stranger to Myself: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Stranger to Myself»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is an unforgettable account of men at war.

A Stranger to Myself — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Stranger to Myself», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Marching orders. In frantic haste, we loaded the cart with ammunition and baggage, put the horses to, and marched, marched.

This was the way defeated troops marched, to avoid encirclement. We didn’t know where we were going.

We marched, marched. [40]

Uncertain Wanderings

FLIGHT

We marched through moonlit forests, over endless roads, plains, and hills, till the day dawned. Then we stopped to rest, slept among thistles and corn stooks, and in the dusk shot off the rest of our ammunition at a deserted village, just to lighten the carts a little.

Ruined villages, debris, and char marked our way. Behind us the last houses went up in flames, woods burned on the horizon, munitions dumps were blown up, and flares, shells, and bombs went up like fireworks into the night sky. By our side were other columns, occasionally the populations of evacuated villages with their carts and animals or else dragging their households on their backs. Old and young women, children, pregnant women, single men, barefoot, in ripped shoes, with sacking wrapped around their feet. We overtook herds of cattle and sheep. An endless column stretched backward and forward, making all the time for the west. In some places the forest was already burning, a last barrier against the advancing Russians.

The dawn burned like a planetary fire, with the terrible force of beauty. We got across the Desna. Our little band found itself in a great mass of fugitives. Women, prisoners, and soldiers were working on positions that would surely fall into Russian hands the very next day. It started to rain and didn’t stop. We marched and marched. The day passed. Night fell on muddy, churned-up roads. Still, we marched on.

We found three hours of sleep in a ravaged village. Onward. We set off again at midnight. Day brightened. Low hill country, expanse of swamps, meadows, fields, and pastures. Very slowly the landscape altered its aspect. We barely took in the rich villages and their beauty in the last light of September. Our progress became a reeling, almost a crawling. We clung on to the cart, deposited rifles and bread sacks in it, let the trembling horses drag us forward, while our legs mechanically moved on.

No more sleep the next night. One man shot himself out of despair and exhaustion. Others remained behind, disappeared; some went on ahead on vehicles and were lost that way. Panic drove us on; uncertainty choked us. Marching and marching.

Late the next morning, we got to Pochep, to be put on trains. The Russians were still pressing; Pochep was due to be abandoned the very next day. We waited timorously, at the end of our strength. We had covered more than ninety miles in two days and three nights. [41]

That was our flight.

We waited to be entrained. Armored cars, assault guns drove up the ramps. Trucks without engines, shot-up artillery pieces, useless tractors were loaded up, wedged tight, and made fast, as train after train rolled westward. There was no room for us. The railwaymen were drunk. Train drivers and firemen slept on the tenders. We plundered the stores and canteens, loaded our cart with boxes of wine and spirits, looted tobacco and cigarettes, put on new uniforms, brought sweets, writing things, and soap out of the basements, where the charges of dynamite had already been put down, and we started to drink. Most of it went bad, was destroyed, or fell into the hands of the victorious Russians. Carts full of planks, beams, coal, and scrap iron were saved. We had to march. Our new destination was Unecha.

We were in despair. Marching and marching. Noonday sun burned down on dusty roads. We followed the tarmac. Then we mutinied.

With not many comrades, I climbed onto a slowly moving truck. Other units melted away; only the drivers remained with their horses. The rest of us got away. No orders were capable of keeping us exhausted men back, and the desire to live broke out in us once more. We rode, and we asked no questions.

The wind cooled our brows, and not until evening did we jump off. Endless columns of motor vehicles were dragging west on the tarmac road; heavily laden troops marched more slowly on the side roads. We rested by the roadside and looked on the map for the village of Staroselye, where we were supposed to overnight.

Slowly, five exhausted soldiers with bleeding and inflamed feet, we followed a track through grassy hills and peaceful fields into the evening. The cool and silent country was already asleep. Lights blinked in a village on a hill. A girl pointed us the way.

It was getting dark by the time we saw the first houses of Staroselye. We ransacked them for eggs, butter, and lard, oblivious to the amazement of the women and the men’s mothers. We settled in one brightly lit room, drew the curtains, got the women to light a fire for us on the stove, to fix us supper. Reluctantly and slowly they obeyed, muttering to themselves. It was an odd feeling. We had no weapons. There were voices outside, whispering but excited.

I drew my knife and went out. A group of young men were standing by the window, listening. They looked at me and asked in broken German if we meant to torch the village. No. But they didn’t believe me.

With heart pounding, I went out onto the street. It was night, dimly lit by a few stars and a pale crescent moon. Whistles sounded in the dark; shouts rang out from the bushes. I went back inside and reported.

Three of my comrades crept through the garden, listened out, and caught the sounds of an excited meeting. All of them were young men with sticks and scythes, now setting off in the direction of our house.

The three men hurried back and told us. We had already broken up the chairs and other furniture, and armed ourselves with clubs and metal bars, and taken our bayonets in our hands.

Now we came charging out and hurled ourselves against the garden fence, crashed through it onto the grass, and raced down the hill. Shots rang out after us. We ran down the track and stopped only when we reached the bottom of the hill from which we had first seen the lights. In that village we found lodging, soldiers, and something to eat. Our sleep was uneasy, but the partisans didn’t bother us.

I was troubled by dreams, dreams of flight, imprisonment, and death. Earlier I would sometimes see only myself wandering in the foggy land, and the spice of adventure affected these fights and travels too. But now the demons chased me through torture and flight, and these dreams seemed not to end.

Early in the morning we returned to the tarmac road. A truck took us along as far as Unecha. I sat on the fender in the wind, saw meadows and stubble fields slip by, woods, shrubs, and villages, and I felt a blissful intoxication. The adventure of being on the road, relying on myself, and free, the ride west, and my near escapes of the past night transported me into a mood of exuberant joie de vivre.

A feeble sun lit the plain; the wind tugged at my hair; my cheeks and brows were seared by the air and dust. The experience of velocity was translated into an inner surge. For a few hours I was free, a drunken traveler in the unknown, a little closer to home, and I enjoyed my liberty like an opiate. I didn’t feel like a soldier, but like a human being, a vagrant abroad in a wonderful world.

The factories and storehouses of Unecha appeared behind thin trees. Railway tracks. Freight trains going by. In the evening, we arrived, collected ourselves, and hooked up with other members of our platoon. More turned up all the time. We learned that some had already been put on trains in Klinzy and that onward transport was expected tomorrow.

That evening we entrained. We weren’t punished and barely scolded. Our comrades treated us to vodka and red wine. I have to say, I missed my freedom and the adventurousness of being on the road.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Stranger to Myself» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.