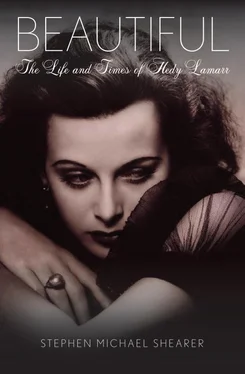

Stephen Michael Shearer

BEAUTIFUL

The Life of Hedy Lamarr

FOR

M.P.W

M.E.W and M.E.W

She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes:

• • •

Which waves in every raven tress,

Or softly lightens o’er her face;

• • •

A mind at peace with all below,

A heart whose love is innocent!

—LORD BYRON

Regarding Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr came into my life—unexpectedly, that’s for sure—one day in the early 1960s. From the minute she greeted me at her front door, I also knew she was a True Original. Hanging prominently on a wall behind her was the ugliest painting I’d ever seen, a wild mix of grays, blacks, and blues, liberally doused with what looked like sand amid colors that seemed to swirl like water circling a drain. I must have blanched, which she interpreted as dumbfounded approval of what I was looking at on that wall. “I painted it,” she said with great pride. “I call it ‘Umbilical Cord.’” I ask you: Who wouldn’t adore an amateur artist who chose as a subject not apples, boats, or trees, but an umbilical cord? I suspected we would become great friends, and we did.

From that moment on we spent a great deal of time together. What surprised me most about Hedy is that she was nothing like the glamorous, mysterious image she projected on screen. She dressed simply. Loved to kick off the shoes. Liked simple foods. Laughed often. Adored charade parties, although game playing was definitely not her strong suit. She liked to do simple things. Picnics. Walks on the beach. Riding bicycles.

Many of the most memorable times I had in Hollywood during my early years there were connected to Hedy, good and bad. Her arrest and trial: bad. A birthday party she gave for me soon afterward: good. The pain on her face when people seemed surprised that at the age of forty-seven she didn’t look exactly as she did at twenty-four: bad. The way the old M-G-M guard was always there for support whenever trouble loomed: good.

The Hedy Lamarr I knew was a blithe spirit, a woman with enormous energy, curiosity, intelligence, and sweetness. If there is any tinge of tragedy connected to her it comes from the fact that, having been blessed with probably the most beautiful face that ever stood in front of a movie camera, this was the only thing people were interested in. Mention her name, and no one ever said, “How is she?” or “Is she well? Is she happy?” It was always, “How does she look?” Hers was, no question, the face of faces, but there was so much more to her than that. Indeed, I feel very privileged to have known her.

—Robert Osborne, prime-time host, Turner Classic Movies television network

It is said that beauty lies in the eye of the beholder. When the young Viennese film actress Hedy Kiesler landed on American shores, she was already heralded as “the most beautiful girl in the world.” Later, her Hollywood studio boss, Louis B. Mayer, and the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer publicity mill perpetuated that image. To Depression-weary movie audiences, she was the most beautiful and most glamorous new film actress of the era.

Few American filmgoers in 1937 would associate the young European actress who cavorted nude in the outdoors and unabashedly simulated sexual passion in facial close-ups in the controversial 1933 picture Ecstasy with M-G-M’s new star. Most Americans never saw that Czechoslovakian film. What they did see (and in droves) was Hedy’s first American picture, Algiers . And as a result, a fresh, new screen favorite—mysterious and alluring—was born.

The respected film critic Parker Tyler once commented about Lamarr’s beauty, “Miss Lamarr doesn’t have to say ‘Yes,’ all she has to do is yawn…. In her perfect will-lessness, Miss Lamarr is, indeed, identified metaphysically with her mesmeric midnight captor, the loving male.” 1

“Of all the glamour queens, surely none was more glamorous than Hedy Lamarr,” wrote the social historian Diane Negra. “She seemed the definition of the word. Of all the stars of the forties and early fifties, she was probably the most classically beautiful, with those huge, marbly eyes, the porcelain skin, the dreamy little smile, and the exotic voice that was an artful combination of Old Vienna and the MGM speech school.” 2

Rechristened Hedy Lamarr, and early on a particular favorite of Metro boss Mayer, beginning in 1937 and up to the early 1950s the breathtakingly exotic actress was meticulously coiffed, gorgeously gowned, and exquisitely photographed in one major film after another, costarring opposite almost Hollywood’s all of M-G-M’s most important leading men.

However, Metro and Mayer did not know exactly what to do with Lamarr. The late British film historian John Kobal wrote:

During her years at MGM, the challenge, the opportunity her mesmerizing appearance offered as a catalyst—if not for art at least for compelling drama—was continually fumbled. Confronted by a priceless object, everybody wanted her, but having got her they were at a loss to know what to do next, which may have been why the powers at MGM kept casting her as a kept woman, repeating her first successful role until inspiration might strike. 3

It never did.

In her first American film, Algiers (1938), Lamarr created a national sensation. Billie Melba Fuller, the author’s mother, recalled that in March 1939, when she was fourteen years old, she was seated in a darkened movie theatre in Ottawa, Illinois, to see the latest picture of her favorite star, Charles Boyer. Like other moviegoers, she was there to also witness Hedy Lamarr’s Hollywood screen debut. Billie would never forget the reaction of the audience to the “unknown” actress’s very first entrance in the film. Hedy Lamarr is photographed at a distance at the start of the scene, approaching the camera in shadow and profile. Suddenly, when she is about to walk off the screen, Lamarr turns her face toward the camera in a stunning close-up.

“One could feel the audience’s anticipation of seeing her face for the first time,” Billie said recently. “It was palpable. Sitting there in the dark, when the shadowed image of Hedy Lamarr suddenly turns her face full to the camera, the impact was audible. Everyone gasped. That’s the only time in my whole life I have ever heard an audience do that at the first sight of an actress in a movie. Hedy Lamarr’s beauty literally took one’s breath away!” 4

In Algiers a new kind of love goddess emerged in film. Usually portraying a vamp, but surprisingly also playing a variety of roles most actresses would never attempt, Lamarr was perpetually typecast as dangerously tempting yet unattainable. Her best film role was in 1941’s H.M. Pulham, Esq. But it would be as Delilah in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1949 hit Samson and Delilah that she will arguably be remembered in motion pictures.

It is almost inconceivable today to comprehend the public and private role of women of her era. In the 1940s, when an attractive actress appeared on the screen, she was little more than set decoration. Nothing was expected of her; only her appearance mattered. (Certainly such female film powerhouses as Bette Davis and Joan Crawford were often filmed attractively. But they were never successfully promoted as appearing “beautiful.”) It was the physical glamour that brought Lamarr to international attention and fame.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу