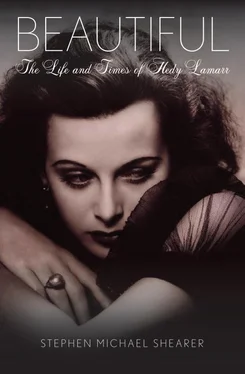

But in Hedy’s personal life that same allure brought disillusionment and heartbreak. By her own admission, her many lovers and numerous husbands were mesmerized and trapped by the image and not by the intelligent, sensitive, and romantic individual who struggled within. Lamarr’s beauty was also her burden, and from it she would never escape.

Hedy Lamarr once commented, “My face has been my misfortune…a mask I cannot remove: I must live with it. I curse it.” 5Yet she also ambitiously bought into its appeal. She was smart in that respect. Even as a child Hedy realized what her visual attributes could achieve for her. But when her physical and professional image began to fade, she was adrift in a world of harsh reality. For Lamarr was indeed a product of her time and environment. Pampered and spoiled as an only child of an affluent family, raised in posh Viennese society, Hedy used her keen mind and remarkable appearance to her advantage, and she exhibited undeniable ambition.

Yet surprisingly always, until the day she died, Hedy Lamarr remained a simple Austrian girl, full of romantic ideals and dreams. In reality she was a very normal human being.

Throughout her life she experienced episodes of unimaginable drama and intrigue, some of which touched upon moments of historical significance. She was always in pursuit of her destiny. She lived in the present, and yet in some ways she was always attempting to escape her past.

Not satisfied with the facts of her life, and certainly not with the religious and political background she inherited, the M-G-M publicity machine embellished and rewrote Lamarr’s biography to such an extent that even she began to believe its mythology. In her often-questionable, ghostwritten “autobiography,” Ecstasy and Me (1966), Lamarr’s life story was never truthfully examined or fully realized. When Ecstasy and Me was published it caused yet another sensation. The consequences of this fiction haunted her for the rest of her life—a cloak of exaggerations and inaccuracies that sadly became the “truth.” Mystery can be damning.

In the mid-1940s, with the world at war, by necessity the role of women in society changed considerably from what it had been. By the end of World War II the exotically mysterious Hedy Lamarr, the image she represented, was passé in motion pictures. In her movies, her lilting Viennese accent undermined an acute acting ability that was never totally exploited on film. Indeed, in her early American pictures, when she was still learning English, she often did not even know what she was saying and consequently recited her lines phonetically.

To filmgoers and critics of that era Hedy Lamarr was considered little more than an exquisite mannequin, not much of an actress, and void of innate intelligence or depth of emotion. In hindsight, her film work begs for reevaluation. In a vast array of surprisingly varied characterizations, there is poignancy and understanding behind her eyes, even if her accent clouds the dialogue. And more important, she was box office; reviews of her work were for the most part positive.

Yet the goddess image distanced Lamarr from personal and professional fulfillment. Louis B. Mayer quickly lost interest in her when her films, though turning profits, did not make back the massive amounts of money he had invested in her. And Mayer failed to offer her appropriate roles and to properly promote her. He simply did not have a clue exactly what to do with this woman. The studio chief was more familiar with how to turn a midwestern shopgirl, Joan Crawford for instance, into a glamorous imitation blue blood for the screen. Rarely was he able to create a motion picture star out of a genuine aristocrat. Hedy intimidated Mayer. For Mayer and a couple of her husbands, there remained a question as to who Hedy Lamarr really was. What was behind that astounding, seemingly unattainable image? And what was the real truth about the life she lived?

Hedy Lamarr led many lives. As an only child she was Princess Hedy, or Hedylendelein, so called by her parents. Early on she evolved into Hedwig Kiesler—artist (perhaps her most real persona), an up-and-coming young actress. Living a pampered and posh life in Vienna and Salzburg in the early 1930s as Madame Mandl, Hedy possessed wealth and status, all the while encircled by political intrigue and ominous danger. She finally made an escape to freedom in 1937. Arriving in Hollywood with a new name, she became Hedy Lamarr, international film star, and was set to uphold the moniker of “the most beautiful girl in the world,” given to her by the legendary theatrical impresario Max Reinhardt.

Sadly, her life became cluttered with drama and literally dozens of distasteful lawsuits, all making for nasty tabloid headlines. Her very name was effectively made into a joke as a result of Mel Brooks’s 1974 comedy film, Blazing Saddles. Then, quite unexpectedly, after the world had largely forgotten and lost sight of Hedy Lamarr, a light shone at the end of the tunnel.

In a startling announcement made just three years before her death in 2000, Hedy Lamarr was awarded an acknowledgment of her true legacy as an inventor of great technological consequence.

No other film star has led such an existence. There were certainly better movie actresses. There were certainly more impressive film careers. Yet Lamarr was unique. She possessed not only that rare quality heralded as glamour but also a brilliant, creative, and sometimes self-destructive mind. Yet she was also a simple, romantic Viennese girl. Hedy Lamarr was a complicated woman born of an era when the circumstances that gave birth to the actress also helped to destroy the woman.

In 2000, the film historian Jeanine Basinger said about Hedy Lamarr, “She herself created her own legend…. She was the last of a movie star type in which we never really knew what her story is.” 6

This is the life story of Hedy Lamarr.

1

Austria

To understand the life of Hedy Lamarr, it is important to understand the world in which she was born. Austria is the heartland of Europe. Vienna, Austria’s capital, was and still is its largest city, located at the northeast end of the Alps and on the right bank of the Danube River. The city has for centuries been renowned for its museums; theatre and opera; the Romanesque architecture of the Ruprechtskirche and the baroque architecture of the Karlskirche; cuisine of schnitzel, pastries, and goulash; and a rich heritage of music, from Tyrolean bands and gypsy Schrammelmusik to the stirring strains of Mozart and the lilting waltzes of Strauss.

At the end of the gilded age, the belle époque, Vienna in 1913 was the grandest city in all of Austria, its population numbering over two million. In Europe at the turn of the last century, Vienna was the magnet to which those seeking better economic and cultural lives were drawn. On April 13, 1913, The New York Times dedicated a full page to the metropolis, entitled “The Gayest City in Europe—Not Paris, but Vienna.” It is a colorful homage by the American music critic and correspondent James Huneker, who wrote lovingly of Vienna as “the gayest city I have ever lived in…,” one where city life “is not feverish as in the French Capital, but natural and continuous…. The Viennese man is an optimist. He regards life not so steadily, or as a whole, but as a gay fragment. Clouds gather, the storm breaks, then the rain stops and the sun floats once more into the blue.” 1

Vienna’s thousands of European exiles before World War I, many of them disenfranchised Jews, adopted all things German, from its culture (the music of Richard Wagner and Gustav Mahler, for example) to its economic structure and its language. The integration of the country was important to its society. By 1900, the expression “Jewish intelligence” was well known in Vienna, causing the writer Hermann Bahr to joke that any aristocrat “who is a little bit smart or has some kind of talent, is immediately considered a Jew; they have no other explanation for it.” 2

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу