Hedy took more direct action, as her father had taught her. “He made me understand that I must make my own decisions,” she said, “mold my own character, think my own thoughts.” She had met Max Reinhardt, the director and impresario, at a party in 1929, when she was fifteen, and he had seemed interested in her. “He had encouraged me by telling me to hold fast to my dream and that if I held fast it would come true.” She held fast, and it did.

After an unhappy term at a Swiss finishing school that she finessed by running away home to Vienna, she scouted a motion-picture studio, Sascha-Film, the largest in the city. To buy time for her assault, she added a zero to a school absence request her mother had signed, turning one hour into ten—two school days. “I knew that the studio employed script girls. I did not have any idea of what script girls are supposed to do, but I knew that they were on the sets all the time watching the actors work—and that was enough for me.” She slipped into the studio and presented herself. “They asked me, ‘Do you know how to be a script girl?’ and I said, ‘No. But may I try?’” Probably because she was pretty as well as brash, the script supervisor laughed and took her on.

She had that day and one more to make good. The film then in production was called Geld auf der Strasse ( Money in the Streets ). There was a minor part for a girl in a nightclub scene. “I applied for it and right away I got it,” Hedy recalled. In this account, for an American magazine, she translates her starting salary as “five dollars a day.”

Then she had to tell her parents that she was dropping out of school at sixteen to become a professional actress. As she remembered the negotiation in 1938:

Well, it was not too bad. They were bewildered a little but not very surprised. They were never surprised at anything I did. And besides, I had been talking movies for so long that they were really prepared for this. My dear father finally laughed and said, “You have been an actress ever since you were a baby!” So my parents did not try to prevent me. They were willing to give me this great wish of my heart.

She recalled it differently later in life. She had persuaded the director, Georg Jacoby, to give her the part. Her parents, she wrote, “were much more difficult to persuade than [Jacoby], because it meant my dropping school. But at last they agreed. My father had never forbidden his little princess anything, and besides, he reasoned that I would soon enough quit of my own accord and go back to school.”

When Geld auf der Strasse wrapped, a better role followed as a secretary in Sturm im Wasserglas ( Storm in a Water Glass ), another Jacoby project. Then Reinhardt cast her in The Weaker Sex . “Reinhardt made me read, meet people, attend plays.” She followed him back to Vienna when he restaged the play there. “Yes, we have no bananas.”

“When you dance with her,” George Weller remembered, “as I did every night for about three months, she is a trifle stiff to the touch. Reedlike, that’s what Hedy Kiesler is, sweet and reedlike, and when she wants to talk to you she doesn’t lean over your shoulder and arch herself out behind like a debutante…. She leans back from you [and] takes a good look in your eyes and a firm grip on your name before she will allow herself to say a word.”

Weller was present when Reinhardt gave Hedy her lifelong byname, a christening later claimed by the Hollywood studio head Louis B. Mayer:

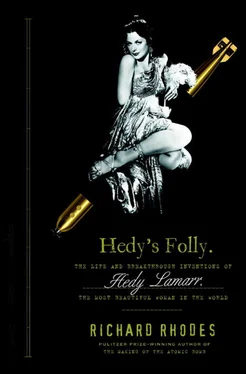

It was at the rehearsal of a cafe scene in a comedy, and the Regisseur [that is, the director] was Reinhardt. There were Viennese newspapermen watching. Suddenly the Herr Professor, a man not given to superlatives, turned to the reporters and mildly pronounced these words: “Hedy Kiesler is the most beautiful girl in the world.” Instantly the reporters put it down. In five minutes the Herr Professor’s sentence, utter and absolute, had been telephoned to the newspapers of the [city center], to be dispatched by press services to other newspapers, other capitals, countries, continents.

The Weaker Sex played in Vienna for one month, from 8 May to 8 June 1931. “Almost before we knew it,” Weller recalled, “another play was in rehearsal.” Hollywood was buying up European actors as it rapidly expanded film production, a trend that would accelerate after 1933 when the Nazis took power in Germany and then in Austria, and Jews saw their civil rights stripped away. The play, Film und Liebe ( Film and Love ), satirized the earlier, commercial phase of the exodus. Weller won the role of “a brash Hollywood director who thought… that Central European talent could be seduced by American gold into immigrating to California.” The female lead as Weller remembered it called for a character “who simply recoiled at the sight of a Hollywood contract,” which would have been a stretch for Hedy. In any case the director offered her a smaller role.

She rejected it. “I’ve never been satisfied,” she explained. “I’ve no sooner done one thing than I am seething inside me to do another thing. And so, almost as soon as I was inside a studio I wanted to be acting in a studio. And as soon as I was acting in a studio, I wanted to be starring in a studio. I wanted to be famous.” Her stage roles had been limited and her reviews mixed. Weller thought she simply “decided for herself… that she wanted no more stage.”

Berlin was the center of filmmaking, and to Berlin she returned that August 1931, looking for work. She found it with the Russian émigré director Alexis Granowsky, who cast her as the mayor’s daughter in a comedy, Die Koffer des Herrn O.F. ( The Trunks of Mr. O.F. ). The cast included her rising Austrian contemporary Peter Lorre in his fourth film role. When Trunks wrapped, in mid-October, Sascha-Film obligingly offered her the female lead in another comedy to be shot in Berlin, Man braucht kein Geld ( One Needs No Money ), opposite Heinz Rühmann, a German film star. Hedy turned seventeen midway through the November production. Die Koffer des Herrn O.F . premiered in Berlin on 2 December. Man braucht kein Geld followed in Vienna on 22 December. “Excellent work by a cast of familiar German actors,” the New York Times would praise Man braucht kein Geld on its New York opening the following fall, “reinforced by Hedy Kiesler, a charming Austrian girl.” It was her first American notice.

Then a truly starring role came to hand. The Czech director Gustav Machatý found Hedy in Berlin and offered her the lead in a Czechoslovakian film, Ekstase ( Ecstasy ), a love story. She was thrilled. “When I had this opportunity to star in [the film],” she recalled, “it was the biggest opportunity I had had. I was mad for this chance, of course.” Shooting was scheduled for July 1932. To fill the intervening months, she replaced one of the four actors in Noël Coward’s comedy Private Lives at the Komödie Theatre.

Whether or not Hedy’s parents read the script of Ekstase isn’t clear from the remaining record. Since she was still a minor, however, they did try to protect her:

I could not go, my father said, unless my mother went too. But I did not want my mother to go…. I was young enough to want to be on my own. What kind of a baby, what kind of an amateur would they think me, I said, if I had to have my mother along to take care of me! Besides, I felt embarrassed when my mother was in the studio, was on the sets watching me. I felt stiff and self-conscious then. I could not feel free and grownup like that. I finally prevailed upon my father to allow me to go with the members of the company. There could be no harm in this.

Читать дальше