After I returned to Canada, I soon received another invitation to Papua New Guinea, this time from women in a town called Wewak in East Sepik province. They were concerned about the loss of their forests and rivers and asked if I would visit. I am a sucker, and so I arranged to go to Papua New Guinea again on my next trip to Australia, in 1994. On that trip, I met Meg Taylor, a remarkable lawyer who later became the Papua New Guinean ambassador to the United States, Mexico, and Canada. She straddles two domains, traditional Papua New Guinea and the aggressive world of industry. I could sense the pull of each sphere on her, which perhaps reflected her background. Meg's mother was a Papua New Guinean, and her father was an Australian, the first white man to cross the island of New Guinea on foot; it is hard to imagine the difficulties he must have encountered, given that each valley is so cut off from the next that all evolved different languages and cultures. Meg remains a force in Papua New Guinea, but she has to weave her way between the traditional values of the country's cultures and the economic demands of industrialized nations.

In East Sepik, the women were desperate to retain their cultural and traditional ways and were upset because some of the chiefs were being lured by alcohol, women, and bribes to sign away their timber for a pittance. The money from cutting the trees wasn't reaching the ordinary people, and the forests were being stripped. I could only offer them suggestions on how communities might develop small-scale economies and relate to them the impact that I had seen Western economic development have on aboriginal people in Canada, Australia, and Brazil.

I was intrigued by Papua New Guinea, because it has one of the largest intact tropical rain forests left on the planet and is still occupied by the indigenous people who own the forests by law. The question is what will happen in the coming years. I promised to help by sending money from a fund I had set up in Australia from the profits of my books there. The women didn't ask for much, but they wanted a chance to develop markets for their traditional products.

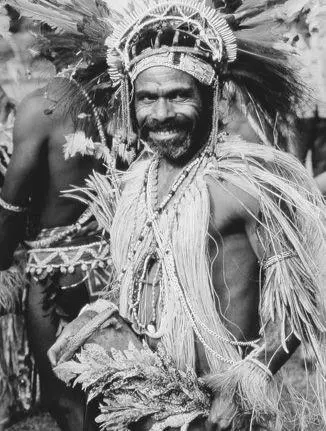

These are the people whose men once wore amazing penis sheaths of many sizes and shapes, and these, I am sure, would be a tourist attraction. Papua New Guineans are excellent carvers, and if their costumes and feather, shell, and ivory necklaces and armbands could be sustainably made, they would be able to generate an income. I was introduced to a man who had developed a “walkabout” sawmill, a setup so light that a pair of men can carry it into the forest and mill a tree on the spot. The lumber can then be carried out manually, and it is valuable enough to make the effort worthwhile yet have a negligible impact on the forest. I kept remembering those two men who carried me on their shoulders as if I were a feather.

Dressed up to entertain

I felt there were alternatives to simply clearing the entire forest for those trees that have high market value, which is what Malaysian and Japanese companies are doing. We have to find ways of getting the money for that wood directly to the people who live in the forests. The resources belong to them, and they have the greatest stake in exploiting them in such a way that the forest will remain in perpetuity for future generations. If the head offices of the logging or mining operations are in Tokyo, Kuala Lumpur, or New York, profits are drained to them, leaving little but dribs and drabs for the people who will have to eke out a living with what is left.

In Wewak, I was taken by motorboat several miles out to sea to a small island. As we slowed and approached the beach, my hosts pointed into the clear water. Below I could see the carcasses of trees lying on their sides. “Those were once on land,” I was told, “but the water has risen and that's why they are there.” Was it thermal expansion of the water due to global warming, they asked me, but I didn't know. I was taken snorkeling in wonderfully clear and warm waters that were filled with fish, and I was thrilled to follow a large sea turtle that swam below me and gradually sank deeper and deeper until it disappeared. Ecotourism was a pretty sure bet here, I felt.

Throughout my visit, my emphasis was not that the people should stay frozen in the past. They must decide on the importance of their traditions and the attraction of economic growth. One of the pilots of a small plane Nick had arranged for me on my first visit had huge holes in his nose and ears, where he clearly wore large plugs in his off time. In the pilot's seat, his appearance seemed rather incongruous, but Papua New Guineans have computers, video cams, and all the other accoutrements of modern society. The question is whether they will slavishly follow the path of globalization, which is reducing cultural and biological diversity all over the world, or whether they will keep their culture and knowledge as the basis for finding a sustainable future.

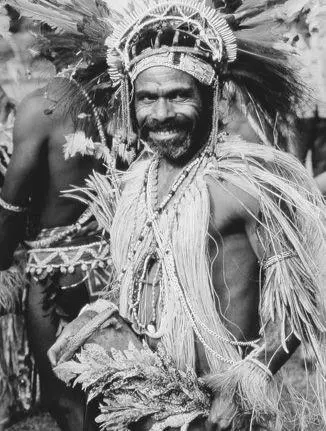

William Takaku, environmental activist, artist, and actor, who starred in the movie Friday with Pierce Brosnan

In my talks, I reiterated the priceless nature of their traditional knowledge, lore painstakingly acquired over thousands of years and, once lost, never recoverable. My message resonated strongly with the young activists I met, but not with the non-Papua New Guineans, who were there for the economic opportunities.

I was scheduled to meet various businesspeople, politicians, and other important folks for a breakfast on my last day. I was placed next to the governor general, a physically imposing Papua New Guinean who had no pretensions and was down to earth in his conversation with me. While he was eating, I looked at his profile and realized I could see through the cartilage of his nose between his nostrils. He must at some time have worn a nosepiece.

I was also scheduled to give a talk that would be broadcast live across Papua New Guinea, a terrific opportunity, because radio was (and is) still the principal means of communication. I gave what must have been an unusual, even radical, speech about the need for the people to decide for themselves what matters most to them and to protect that above all else. They shouldn't allow officials like the World Bank people to set the agenda for them. My talk was met with great enthusiasm.

Unknown to us, as my speech began, an Australian who was in mining in Papua New Guinea became so incensed that he drove to the radio station that was beaming my speech, walked in, and pulled the wires out of the console, stopping the broadcast! Blithely ignorant of this, I went to the airport after the broadcast and left the country. I heard only later that inflamed listeners called in, many saying the expat should be killed, and that he was subsequently kicked out of the country. In April 2005, I attended a conference of Pacific countries on tourism, held in Macao, where a Papua New Guinean came up to me and said, “I was there at your speech that morning.” Apparently it has become legendary.

FIFTEEN

KYOTO AND CLIMATE CHANGE

HUMAN BEINGS HAVE become so powerful that we are altering the chemistry of the very atmosphere that sustains us. Scientists have speculated on this possibility since the nineteenth century, but for the average person, it has only recently become a matter of concern.

We tend to assume that the atmosphere reaches the heavens. But air within which life can exist is only five or six miles deep; many of us can easily run that distance. When I interviewed Canadian astronaut Julie Payette for the film series The Sacred Balance , she said that each time she circled the planet on her voyage in space she could see with every sunrise and sunset the thin layer just above the earth — the atmosphere. “We were way above it,” she said. “Below that thin layer is where life flourishes and above it, there is nothing; it's a vacuum.”

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Devot & Anal [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/485905/david-jagusson-devot-anal-hardcore-bdsm-thumb.webp)