The halls were filled with the babble of people, official delegates from dozens of countries, environmentalists and other NGOs, lobbyists for the fossil-fuels industry, and the media. Altogether, it was a mélange of perspectives and priorities. At the meetings, leading scientists talked about the latest evidence for climate change, environmental groups called for serious cuts in emissions, and government delegates wrestled with lobbyists working to sabotage the process by driving it off the rails. The Australian delegation complained bitterly that their country was special, a big country with a sparse population that had few rivers for hydroelectric power and therefore was dependent on highly polluting coal-fired plants.

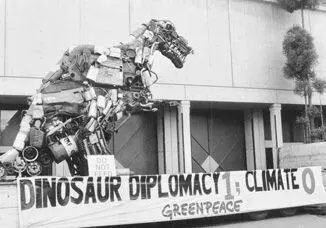

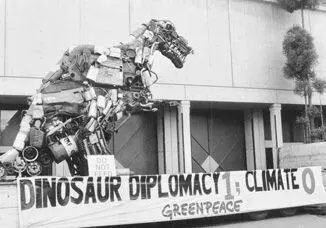

The Greenpeace display outside the conference hall in Kyoto

The insurance industry was the one large group in the business community that took climate change very seriously. Their actuarial data were dramatic — claims for climate-related damage like fires, floods, droughts, and storms were rising dramatically, as were the number of insurance companies going out of business.

The European Union (EU) was very concerned about climate change and wanted serious cuts in the range of 15 percent below 1990 emission levels. Aligned against them were the JUSCANZ countries (Japan, United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), which formed a bloc working to water down the target. There were enormous debates about whether to allow Canada, and similar countries, to be given credit for the fact that its boreal forest absorbed carbon dioxide, therefore acting as a “carbon sink”; others wanted “emissions credits” to be traded so that polluting countries or industries could avoid reducing their emissions by paying for someone else's “share” of the atmosphere.

In such surroundings, the cynics could suggest the final decisions and targets were far too shallow to be effective and far too expensive for what would be achieved. But I believe the final outcome of the Kyoto deliberations was extremely important for what it signified. Kyoto signaled the recognition that the atmosphere is finite, that human activity has saturated it with emissions from fossil-fuel-burning vehicles and industries, and that we are adding more carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases than the biosphere can handle. For the first time, governments and industries had to acknowledge that there can't be endless growth.

The atmosphere is not confined within national boundaries; it is a single entity shared by all people and organisms on Earth. The industrialized nations created the problem with their highly productive fossil-fuel-dependent economies. As an illustration of the disparity between the industrialized and nonindustrialized nations, Canada's 30 million people use as much energy as the entire African population of 900 million. In 1976, when I first visited China, which had thirty times Canada's population, it was using the same amount of oil and gas as Canada. I wrote at the time that if every Chinese wanted a motorbike, the results would be devastating. Now, a quarter of a century later, most Chinese aren't interested in bikes; they want cars, and with a booming economy and a growing middle class, more and more can afford them.

In 1997, the challenge was how to divvy up the atmosphere equitably. Countries like the United States, Australia, and Canada were heavy emitters, whereas countries like Russia were “under-emitters,” since their antiquated and polluting industries were not globally competitive and were being forced to shut down; on a per capita basis, therefore, Russian people already had a lower emission output than the global emission target to be set at Kyoto. So, it was argued, such countries should be allowed to sell their “unused” share of the atmosphere to companies or countries that might not meet the target. This was a ludicrous idea, however, because even the lower emission rates were above the rates that would have to be reached to enable all greenhouse gases to be absorbed by plants. Allowing others to pay for the low emitters' “share” of the atmosphere was merely a loophole permitting those who had enough money to keep on polluting.

Alberta sent a delegation to lobby against the Kyoto negotiations. I remember Rahim Jaffer, the right-wing Reform party's member of Parliament from Edmonton, Alberta, loudly denying the evidence that climate change was happening, even though the overwhelming majority of delegates were not disputing the science. Europeans were appalled at the intransigence of the official JUSCANZ delegates, especially from the United States, which is the largest emitter on the planet; they were determined to set lower emissions targets. A stalemate loomed between those calling for significant reductions on the order of 15 percent below 1990 levels and those arguing that such goals were far too costly and ineffective. I didn't have access to the official Australian and American delegates, but environmentalists from the two countries were out-spoken in their condemnation of the position of their governments. Many American environmentalists pinned their hopes on the arrival of U.S. vice president Al Gore.

Day after day the circus continued, as environmental groups performed a variety of stunts to try to gain attention from the media. Randy Hayes, the head of the Rainforest Action Network, led a conga line through the building to protest the position of his own country, the United States. I've always admired Randy for his originality and daring in the way he does things. I attended another conference in Japan at which he infuriated journalists by calling Japan an “environmental bandit.”

At Kyoto, the David Suzuki Foundation called a press conference in which we used stacks of pop cans to illustrate the disparity in energy use by industrialized and developing countries. Energy use by an average person in African countries like Zimbabwe was represented by 1 can, India and China by 5 and 15 cans, respectively, and Japan and European countries by 55 to 65 cans. Canada came near the top with 96, and the U.S. was tops with a whopping 120 cans. It made for a great photo.

Press conference using pop cans to represent greenhouse gas emission levels. Left to right : me, Steven Guibeault (Greenpeace Canada), and Louise Comeau (Sierra Club Canada).

The JUSCANZ allies were at loggerheads with the European Union, which wanted an aggressive approach to reducing emissions. Again, cynics argued that EU nations could make deeper cuts more easily. For example, Germany was aided by the fact that when East and West Germany were united, the antiquated, polluting plants of East Germany were shut down, thereby reducing the unified country's overall output and making it easier to meet targets. Since then, however, Germany has become the world leader in wind power, erecting windmills at home and exporting the technology abroad. Germany stands as a shining example of the opportunities created by taking the challenge seriously. Great Britain was also phasing out its outmoded coal-burning plants and therefore would find it easier to meet any target. Since then, however, Prime Minister Tony Blair has committed the United Kingdom to a 60 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2040 and promises that cuts can be ramped up even further if the science demands it. Now that is a serious commitment.

BECAUSE OF JUSCANZ OPPOSITION, it began to look as if the proceedings would fail. But then Vice President Gore arrived. Environmentalists adored him because, as he described in his book Earth in the Balance , he understood the issues.

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Devot & Anal [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/485905/david-jagusson-devot-anal-hardcore-bdsm-thumb.webp)