In each village, I was treated generously, feted, and fed traditional foods. In one community, chicken, yams, and other root vegetables had been covered with leaves in a hole and a fire lit on top. Hours later, the meal was excavated and served — delicious.

Everywhere I went, people were spitting. This is disconcerting, because the spit is red from the eating of betel nuts, which also stain and etch cavities in the teeth. Nick told me the nuts — the seeds of betel palm — induce a pleasant buzz, but I was leery and never tried it. I wish I had, but I didn't want to stain my teeth. I was even more worried that to activate the drug in the plant, it has to be combined with a strong alkali that can burn the mouth. I didn't want to do that to my tongue or cheeks.

What you do is chew the nut to make a fibrous paste and then flatten it onto your tongue. The alkali formed by crushed, burned clam-shells is placed onto the bed of betel nut on your tongue. You fold the flattened betel nut around the clamshells, using your tongue and the roof of your mouth so the alkali doesn't burn anything, and then the whole mass is chewed and mixed. The mixture turns red and the active ingredient is created. The big question is, how did people ever figure out such an elaborate process?

Like the Kaiapo in the Amazon, the people in these remote villages were almost completely self-sufficient. The Nature of Things with David Suzuki broadcast a two-part series based on a remarkable exchange between a tribe in Papua New Guinea and a Salish First Nation community in British Columbia. First the Canadian group went to Papua New Guinea for several weeks, and the following year the Papua New Guinea group visited B.C. One of the Papua New Guineans commented that everything they had received while they stayed in B.C. — food, clothing, gifts — had to be bought with money that had to be earned. “When they visited us,” he said, “everything we used came from the land.”

Trying out the drum given to me by people in the Kakoda Mountains in Papua New Guinea

Nevertheless, the products of the industrial economy were visible in every Papua New Guinea village I saw, from metal pots and pans to woven cloth in shirts and pants to radios and chain saws. I kept thinking how different it must have been to go there in the 1950s and 1960s. That's when biologists like the Harvard ant expert E.O. Wilson, and the University of California (Los Angeles) bird authority Jared Diamond had studied in these wild lands. Having become an independent nation, Papua New Guinea must find a source of revenue for the government and bring the benefits of education and medical care to very remote communities. The challenge is to decide whether traditional customs and practices have value in a global economy and, if they do, how to protect them while generating incomes.

Ecotourism seemed to be an obvious potential source of revenue, since millions of people are avid bird-watchers and birds abound in the tropical forests. As well, the surrounding seas are crystal clear and teeming with fish, turtles, and coral. But I couldn't see how development of infrastructure — buildings, water, food, beds, blankets, and so on — and personnel could be organized without a huge disruption in traditional ways. In most villages, I slept above the ground on a platform covered with a floor of branches, and in one lovely location I slept right beside a glistening-white, sandy seashore. There would be enough people willing to rough it as I did, but it would be difficult to ensure there was food and first aid for cuts and infections, bites, and possible accidents.

I had been treated with great honor and respect and given gifts in each village as if I were royalty. After this tour of the villages, I returned to Port Moresby, where Nick had arranged for me to meet environmentalists. Many had fought against logging and mining, but there was great frustration because of the corruption of government officials. I couldn't figure out why people spoke so openly to me of their problems and asked me for advice, until I learned that there was some television reception in the city from Australia and that radio was big in the country. I learned that some of my programs and interviews had already been broadcast in Papua New Guinea.

In a speech in Port Moresby at the university, I suggested that by any objective assessment of natural resources — intact forests, abundant wildlife, clean water and air, rich oceans — Papua New Guineans must rate among the wealthiest people on Earth. The World Bank and transnational corporations were pressing them to adopt their ideas of progress and development; according to them, Papua New Guinea seemed poor. If Papua New Guineans could keep the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) off their backs, I said, they could define what development means to them in a way that fits their culture and thus chart their own way into the future.

My remarks were covered by the media, and on my last night in Port Moresby, I received a note in my room from Ajay Chibber, World Bank division chief for Indonesia and the Pacific Islands. He had heard a broadcast of some of my remarks about the World Bank and was most upset; he said I was completely misinformed and demanded to see me to set me straight.

At six o'clock the next morning, I met Chibber and Pirouz HamidianRad, a senior economist in the East Asia department of the World Bank. Chibber waded right in and said, “You and I are well off. We don't have the right to deny the poor people of the world an opportunity to improve their lives.” I agreed, but I asked who is really “poor” and how we define “improvement.” I suggested that the World Bank was forcing the so-called developing world to accept its definitions, that global economics overvalues human capital while ignoring the services of the natural world as “externalities.” That's why forests and rivers, for example, which have provided a living for people for millennia, have economic value as defined by people like Chibber only when humans “develop” them by cutting down the trees or damming the rivers. I suggested there are other ways of measuring wealth and progress, to which Chibber retorted, “People around the world are better off now than they have ever been. There's more food than ever before in history, and it's because of economic development.”

Chibber's statement encapsulated the belief that has concentrated wealth in a few hands while creating ecological degradation and poverty for many from Sarawak in Malaysia to Brazil to Kenya. I told him that leading scientists were warning about ecological disaster, to which he responded: “Scientists said twenty years ago there would be a major famine and large numbers of people would die. It never happened. They often exaggerate.” So he wrote off scientists as lacking credibility. I wrote about him in a column, which I later included in my book Time to Change , and was gratified to learn years later that he had been removed from his position after my visit, though he went on to other World Bank posts.

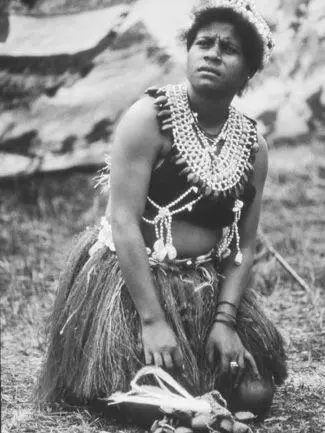

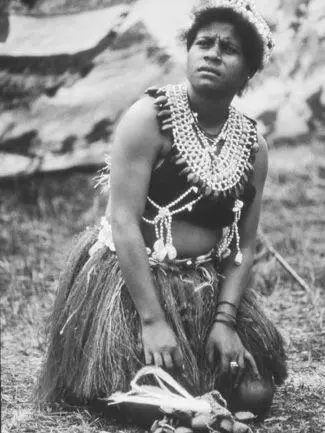

Typical regalia

The problem with groups like the IMF and World Bank is that everything is viewed through the perceptual lens of economics. Where people and communities have lived well through subsistence agriculture, fishing, and forestry for thousands of years, revenues are not generated for governments or corporations. By economics measures, countries that subsist traditionally become “developing” or “back-ward” and therefore “poor.” An example of the consequence of conventional economic “progress” is described by Richard J. Barnet and John Cavanagh in Global Dreams: Imperial Corporations and the New World Order : “Sabritos [the Mexican subsidiary of Frito-Lay, owned by PepsiCo] buys potatoes in Mexico, cuts them up and puts them in a bag. Then they sell the potato chips for a hundred times what they paid the farmer for the potatoes.”

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Devot & Anal [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/485905/david-jagusson-devot-anal-hardcore-bdsm-thumb.webp)