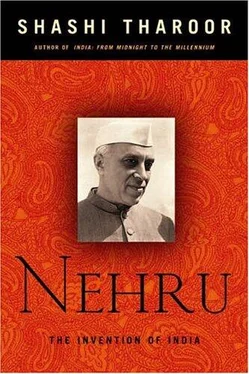

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The mantra of self-sufficiency might have made some sense if, behind these protectionist walls, Indian business had been encouraged to thrive. Despite the difficulties placed in their way by the British Raj, Indian corporate houses like those of the Birlas, Tatas, and Kirloskars had built impressive business establishments by the time of independence, and could conceivably have taken on the world. Instead they found themselves being hobbled by regulations and restrictions, inspired by Nehru’s socialist

mistrust of the profit motive, on every conceivable aspect of economic activity: whether they could invest in a new product or a new capacity, where they could invest, how many people they could hire, whether they could fire them, what sort of expansion or diversification they could undertake, where they could sell and for how much. Initiative was stifled, government permission was mandatory before any expansion or diversification, and a mind-boggling array of permits and licenses were required before the slightest new undertaking. It is sadly impossible to quantify the economic losses inflicted on India over decades of entrepreneurs frittering away their energies in queuing for licenses rather than manufacturing products, paying bribes instead of hiring workers, wooing politicians instead of understanding consumers, “getting things done” through bureaucrats rather than doing things for themselves. This, too, is Nehru’s legacy.

The combination of internal controls and international protectionism gave India a distorted economy, underproductive and grossly inefficient, making too few goods of too low a quality at too high a price. Exports of manufactured goods grew at an annual rate of 0.1 percent until 1985; India’s share of world trade fell by fourfifths. Per capita income, with a burgeoning population and a modest increase in GDP, anchored India firmly to the bottom third of the world rankings. The public sector, however, grew in size though not in production, to become the largest in the world outside the Communist bloc. Meanwhile, income disparities persisted, the poor remained mired in a poverty all the more wretched for the lack of means of escape from it in a controlled economy, the public sector sat entrenched on the “commanding heights” and looked down upon the toiling, overtaxed middle class, and only bureaucrats, politicians, and a small elite of protected businessmen flourished from the management of scarcity.

India’s curse, the economist Jagdish Bhagwati once observed, was to be afflicted by brilliant economists. Nehru had a weakness for such men: people like P. C. Mahalanobis, who combined intellectual brilliance and ideological wrongheadedness in equal measure, but who was given free rein by Jawaharlal to drive India’s economy into a quicksand of regulatory red tape surrounding a mirage of planning. Nearly three decades after Nehru’s death and long after the rest of the developing world (led by China) had demonstrated the success of a different path, a new Congress prime minister, P. V. Narasimha Rao, launched the country on economic reforms. In place of the Nehruvian mantra of self-sufficiency, India was to become more closely integrated into the world economic system. This repudiation of Nehruvianism has survived and become part of the new conventional wisdom. Though there is no doubt that economic reform faces serious political obstacles in democratic India, and change is often made with the hesitancy of governments looking over their electoral shoulders, there is now a definitive rupture of the Nehruvian link between democracy and socialism: one is no longer the corollary of the other. The bogey of the East India Company has finally been laid to rest.

And yet there is no denying one vital legacy of Nehru’s economic planning — the creation of an infrastructure for excellence in science and technology, which has become a source of great self-confidence and competitive advantage for the country today. Nehru was always fascinated by science and scientists; he made it a point to attend the annual Indian Science Congress every year, and he gave free rein (and taxpayers’ money) to scientists in whom he had confidence to build high-quality institutions. Men like Homi Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai constructed the platform for Indian accomplishments in the fields of atomic energy and space research; they and their successors have given the country a scientific establishment without peer in the developing world. Jawaharlal’s establishment of the Indian Institutes of Technology (and the spur they provided to other lesser institutions) have produced many of the finest minds in Silicon Valley; today, an IIT degree is held in the same reverence in the U.S. as one from MIT or Caltech, and India’s extraordinary leadership in the software industry is the indirect result of Jawaharlal Nehru’s faith in scientific education.

Of course this record also masks much mediocrity; overbureaucratized and underfunded scientific institutes that prompted gifted researchers like Har Gobind Khurana and Subramanyam Chandrasekhar to take their talents abroad and win Nobel Prizes for the U.S. rather than India. It is striking that post-independence India has not replicated, at any of Nehru’s much-vaunted scientific institutions, the success of pre-independence scientists like C. V. Raman, Satyen Bose, or Meghnad Saha, who had left their marks on the world of physics in the first thirty years of the twentieth century with the Raman effect, the Bose-Einstein statistics, and the Saha equation. Still, Nehru left India with the world’s second-largest pool of trained scientists and engineers, integrated into the global intellectual system, to a degree without parallel outside the developed West.

Nehru was skeptical of Western claims to stand for freedom and democracy when India’s historical experience of colonial oppression and exploitation appeared to bear out the opposite. His conclusion was to see a moral equivalence between the two rival power blocs in the cold war, a position that led to nonalignment. Nehru saw this as the only possible stance compatible with the self-respect of a newly independent nation, and one which entitled India to take an independent position on each international issue. The limitations of his approach became apparent near the end of his own life, and today the end of the cold war has left India without a global conflict to be nonaligned against. Nonalignment, its defenders suggested, gave credibility to Indian nationalism by providing it with an overarching international purpose; without it, some questioned whether the idea of India could have stood its ground. But the point about the nationalist idea in India was that, for all the Nehruvian rhetoric, it was not dependent on an internationalist mission: its principal relevance was internal, in “creating Indians” out of the world’s most disparate collection of fellow citizens. Today one might argue that the changes in India’s external orientation necessitated by its economic reforms and by the emergence of the United States as the sole superpower have made nonalignment a rhetorical device at best, an irrelevance at worst. Be that as it may, the point remains that nonalignment is no longer a sufficient explanation for India’s interests on the world stage. Once again, Nehruvianism is passé.

A retired Indian diplomat, Badruddin Tyabji, surveying the conduct of Nehru’s foreign policy after Nehru’s death, lamented sardonically:

Subjectivity still rules the roost, though the great

Subject himself died in 1964. His successors now

quibble over the contents of his “system,” though

he had no system. He had only behaved like himself,

and no one can do that any more for him.

The political ethos Nehru promoted was one of staunch anti-imperialism, a determination to safeguard India against foreign domination and internal division, and a commitment — at least in principle — to the uplift of the poorest sections of Indian society. These concerns fused together in the four pillars of Nehruvianism. If they were infused by what sometimes seemed excessively idealist rhetoric, Jawaharlal had a typical retort: “idealism,” he declared, “is the realism of tomorrow.” Tomorrow, however, has a habit of finding its own realisms. The last Congress Party government of Prime Minister Narasimha Rao paid little but lip service to the traditional leitmotivs of the Nehru legacy. Instead, Rao tried to manage the contradictory pulls of India’s various particularist tendencies by seeking to accommodate them in a new consensus: economic reforms to invite foreign investment, to reduce the government’s power to command the economy, and to spur growth, coupled with politics that gave a little to each new group demand. The governments that have followed his have gone even further, even beginning to dismantle the public sector that was among Nehru’s proudest creations.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.