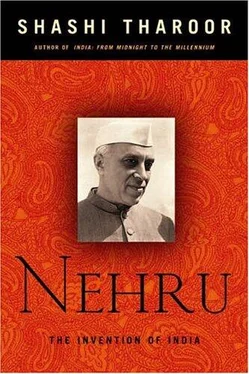

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This has been augmented by the increasing importance of caste as a factor in the mobilization of votes. Nehru scorned the practice, though some of his aides were not above exploiting caste-based vote banks, but today candidates are picked by their parties principally with an eye to the caste loyalties they can call upon; often their appeal is overtly to voters of their own caste or subcaste, urging them to elect one of their own. The result has been a phenomenon Nehru would never have imagined, and which yet seems inevitable: the growth of caste-consciousness and casteism throughout Indian society. An uncle of mine by marriage, who was born just before independence, put it ironically to me not long ago: “In my grandparents’ time, caste governed their lives: they ate, socialized, married, lived, according to caste rules. In my parents’ time, during the nationalist movement, they were encouraged by Gandhi and Nehru to reject caste; we dropped our caste-derived surnames and declared caste a social evil. As a result, when I grew up, I was unaware of caste; it was an irrelevance at school, at work, in my social contacts; the last thing I thought about was the caste of someone I met. Now, in my children’s generation, the wheel has come full circle. Caste is all-important again. Your caste determines your opportunities, your prospects, your promotions. You can’t go forward unless you’re a Backward.” Caste politics as it is practiced in India today is the very antithesis of the political legacy Nehru had hoped to leave.

This damaging consequence of well-intentioned social and political engineering means that, in the five decades since independence, India has failed to create a single Indian community of the kind Nehru spoke about. Instead, there is greater consciousness than ever of what divides us: religion, region, caste, language, ethnicity. The Indian political system has become looser and more fragmented. Politicians mobilize support on ever-narrower lines of caste, subcaste, region, and religion. In terms of political identity, it has become more important to be a “backward caste” Yadav, a “tribal” Bodo, or a sectarian Muslim than to be an Indian. And every group claimed a larger share of a national economic pie that had long since stopped growing.

The modest size of that economic pie was itself a Nehruvian legacy. Other countries put authoritarian political structures in place to drive economic growth; in some cases, notably in Southeast Asia, this worked, and political liberalization has only slowly begun to follow in the wake of prosperity. Nehru recognized from the start that prosperity without democracy would be untenable; for him the central challenge in a pluralist society was to order national affairs to give everyone an even break, rather than to break even. In the process, Nehru’s India put the political cart before the economic horse, shackling it to statist controls that emphasized distributive justice above economic growth, and discouraged free enterprise and foreign investment. The reasons for this were embedded in the Indian freedom struggle: since the British had come to trade and stayed on to rule, Nehruvian nationalists were deeply suspicious of foreigners approaching them for commercial motives.

Nehru, like many Third World nationalists, saw the imperialism that had subjugated his people as the logical extension of international capitalism, for which he therefore felt a deep mistrust. As an idealist profoundly moved by the poverty and suffering of the vast majority of his countrymen under colonial capitalism, Nehru was attracted to noncapitalist solutions for their problems. The ideas of Fabian Socialism captured an entire generation of English-educated Indians; Nehru was no exception. As a democrat, he saw the economic well-being of the poor as indispensable for their political empowerment, and he could not entrust its attainment to the rich. In addition, the seeming success of the Soviet model? which Nehru admired for bringing about the industrialization and modernization of a large, feudal, and backward multinational state not unlike his own — institutions. Men like Homi appeared to offer a valuable example for India. Like many others of his generation, Nehru thought that central planning, state control of the “commanding heights” of the economy, and government-directed development were the “scientific” and “rational” means of creating social prosperity and ensuring its equitable distribution.

Self-sufficiency and self-reliance thus became the twin mantras: the prospect of allowing a Western corporation into India to “exploit” its resources immediately revived memories of British oppression. (It is ironic that in the West, freedom is associated axiomatically with capitalism, whereas in the postcolonial world freedom was seen as freedom from the depredations of foreign capital.) “Self-reliance” thus became a slogan and a watchword: it guaranteed both political freedom and freedom from economic exploitation. The result was a state that ensured political freedom but presided over; economic stagnation; that regulated entrepreneurial activity through a system of licenses, permits, and quotas that promoted both corruption and inefficiency but did little to promote growth; that enshrined bureaucratic power at the expense of individual enterprise. For most of the first five decades since independence, India pursued an economic policy of subsidizing unproductivity, regulating stagnation, and distributing poverty. Nehru called this socialism.

The logic behind this approach, and for the dominance of the public sector, was a compound of nationalism and idealism: the conviction that items vital for the economic well-being of Indians must remain in Indian hands — not the hands of Indians seeking to profit from such activity, but the disinterested hands of the state, the father-and-mother to all Indians. It was sustained by the assumption that the public sector was a good in itself; that, even if it was not efficient or productive or competitive, it employed large numbers of Indians, gave them a stake in worshipping at Nehru’s “new temples of modern India,” and kept the country free from the depredations of profit-oriented capitalists who would enslave the country in the process of selling it what it needed. In this kind of thinking, performance was not a relevant criterion for judging the utility of the public sector: its inefficiencies were masked by generous subsidies from the national exchequer, and a combination of vested interests — socialist ideologues, bureaucratic management, self-protective trade unions, and captive markets — kept it beyond political criticism.

But since the public sector was involved in economic activity, it was difficult for it to be entirely exempt from economic yardsticks. Yet most of Nehru’s public-sector companies made losses, draining away the Indian taxpayers’ money. Several of the state-owned companies even today are kept running merely to provide jobs — or, less positively, to prevent the “social costs” (job losses, poverty, political fallout) that would result from closing them down. All this we owe to Nehru. Since economic self-sufficiency was seen by the Nehruvians as the only possible guarantee of political independence, extreme protectionism was imposed: high tariff barriers (import duties of 350 percent were not uncommon, and the top rate as recently as 1991 was 300 percent), severe restrictions on the entry of foreign goods, capital, and technology, and great pride in the manufacture within India of goods that were obsolete, inefficient, and shoddy but recognizably Indian (like the clunky Ambassador car, a revamped 1948 Morris Oxford produced by a Birla quasi monopoly, which had a steering mechanism with the subtlety of an oxcart, which guzzled gasoline like a sheikh and would shake like a guzzler, and yet enjoyed waiting lists of several years at all the dealers).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.